'Is Xi's China stable?'

'No one can say whether the regime will fall all at once or if its leaders are devising a new solid and competitive -- anything but democratic -- model.'

A fascinating excerpt from Francois Bougon's Inside The Mind of Xi Jinping.

Is there such a thing as 'Xi-ism'? Perhaps something similar to Maoism-that sinified version of Marxism-Leninism that once appealed to so many Western youths? This is an important question in China and is heavily discussed within academic circles.

It is all the more interesting since each leader leaves his mark, a sort of theoretical legacy, in the Constitution and Party statutes.

This comes in the form of a personal slogan, which serves as a summary of the leader's political objectives and is repeated like a mantra and reprised by his successors. The Xi 'magic formula' adopted by the 19th Congress in autumn 2017 was 'Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era'.

First of all, it is worth noting that Xi has managed the incredible feat of having his name inscribed in the Communist party constitution, putting himself on the same level as Mao alone. 'Mao Zedong Thought' was added in 1945 at the 8th Congress.

Even Deng's 'Socialism with Chinese characteristics' was not added until after his death, adopted by the 15th Congress as 'Deng Xiaoping Theory' in 1997.

Xi, then, has been given lingxiu status, a term which means 'leader' in Chinese, but which up until that point had been reserved for Mao and Deng.

The 'Xi Jinping Thought' formula announced the start of a new 30-year era, ending in 2050, following those of Maoism and of Deng and his heirs, Jiang Xemin and Hu Jintao.

Then US president Richard M Nixon's famous flight to China followed in February 1972.

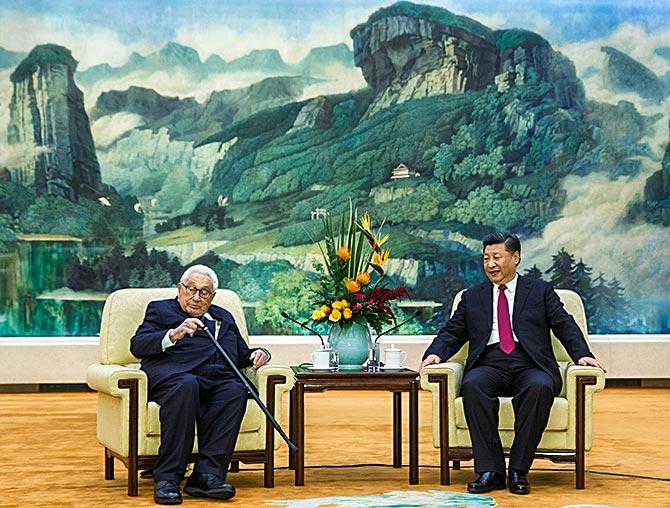

Dr Kissinger has been most vocal about a better US-China relationship ion the Trump era. Photograph: Thomas Peter/Reuters

Xi has asserted himself as an all-powerful master and guide. He is to lead China down the path of a two-stage development to become 'a great modern socialist country': between 2020 and 2035, the aim is to achieve a 'moderately prosperous society', the Confucian expression used by Deng; then, between 2035 and 2050, the Chinese nation will once again be a leading world economy.

It will be 'prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious, and beautiful,' Xi declared to 2,200 delegates. Democratic, that is, in the party's sense of the word, of course, and not that of despised Western norms.

The good Marxist Xi also pointed out that 'the principal contradiction' facing Chinese society was between 'unbalanced and inadequate development and the people's ever-growing needs for a better life'.

For Xi, this new era-his era-will be that of a fully assumed rejuvenation. About time, one might say. The late 19th century reformers had dreamed of it, the party will fulfill it: 'The Chinese nation, with an entirely new posture, now stands tall and firm in the East,' he declared.

To get to this point, Xi had put the party back at the heart of things, to control society and the economy and achieve the 'Chinese Dream'. He announced with pride: 'National rejuvenation has been the greatest dream of the Chinese people since modern times began. At its founding, the Communist Party of China made realising Communism its highest ideal and its ultimate goal, and shouldered the historic mission of national rejuvenation.'

'In pursuing this goal, the party has united the Chinese people and led them through arduous struggles to epic accomplishments'.

When it comes down to it, on which side does Xi Jinping fall in the battle of ideas?

He is neither entirely on the right, which defends constitutional evolution, nor entirely on the left, where the authoritarian Maoist nostalgics are gathered.

Like all politicians, he manoeuvres, tinkers, and seeks his balance, giving his encouragement here and there. There is no indication that he is the author of a coherent doctrine of his own.

Everyone has their own take on this matter, and the dissident writer Murong Xuecun sees in these trends the rise of a 'new market totalitarianism', a totalitarianism adapted to the 21st century.

Thus, where Hu Jintao was overwhelmed by social media, Xi Jinping can force social networks into line and impose his law on digital spaces. He even uses tweets and Facebook posts himself.

The personality cult, back with a vengeance, has had to resort to the codes of trendy youth. 'The people are granted some personal freedoms,' Murong explains, 'but everyone is aware that these can be revoked at any time and without warning'.

Despite this acclimatisation to the digital environment, he predicts that the regime will fall 'by 2035'.

'This system of social "harmonisation" has reached its limit, and many people expect another Tiananmen, like in 1989.'

Indeed, this is the final and most important question: Is Xi's China stable?

Of course, it is vain to speculate on the country's future, and no one can say whether the regime will fall all at once or if its leaders are devising a new enviable, solid, and competitive -- anything but democratic -- model.

It is important to note, however, that Sinologists have become increasingly sceptical since 2015. Until then, opinions had diverged.

Some believed that, since 1949, the party had demonstrated its ability to adapt to different circumstances, in some sense the world's first 'Darwinian' Leninist Party.

Others constantly predicted the fall of the regime due to economic vulnerabilities and social tensions, echoing Gordon Chang's opinion -- he had become the object of ridicule in 2001 for authoring a book in which he predicted the fall of the Communist system by 2011.

By contrast, few today believe the regime will survive. A penny appears to have dropped among the world's China experts: The American sinologist David Shambaugh, who had been confident of Beijing's strength until 2015, and whose position was well-known, joined the ranks of the sceptics.

In an extremely critical article published in The Wall Street Journal, he predicted an imminent end to the regime. The latter, he argued, was down to its last cards:

'The endgame of Chinese Communist rule... has progressed further than many think. We don't know what the pathway from now until the end will look like, of course.'

'It will probably be highly unstable and unsettled. But until the system begins to unravel in some obvious way, those inside of it will play along -- thus contributing to the facade of stability.'

'Communist rule in China is unlikely to end quietly. A single event is unlikely to trigger a peaceful implosion of the regime. Its demise is likely to be protracted, messy and violent.'

'I wouldn't rule out the possibility that Mr Xi will be deposed in a power struggle or coup d'état.'

'With his aggressive anticorruption campaign... he is overplaying a weak hand and deeply aggravating key party, State, military and commercial constituencies.'

To stress his point, Shambaugh identified several signs of weakness: flight of the rich from the country, political repression, lack of faith in the system among many of its followers, an exhausted economy, and corruption, an evil which, without the rule of law and with the media under the regime's thumb, is deeply entrenched.

Shambaugh referred to a personal experience, a conference in Beijing on the 'Chinese Dream' organised by a party-affiliated think-tank:

'We sat through two days of mind-numbing, non-stop presentations by two dozen party scholars -- but their faces were frozen, their body language was wooden, and their boredom was palpable. They feigned compliance with the party and their leader's latest mantra. But it was evident that the propaganda had lost its power, and the emperor had no clothes.'

To save the system would take reform, Shambaugh asserted, but Xi has not come around to it.

To save the system would take reform, Shambaugh asserted, but Xi has not come around to it.

Thus, he concluded: 'We cannot predict when Chinese Communism will collapse, but it is hard not to conclude that we are witnessing its final phase. The CCP is the world's second-longest ruling regime (behind only North Korea), and no party can rule forever'.

To quote another eminent China specialist, Jean-Pierre Cabestan, 'barring any interior or international catastrophe, it is highly probably that the current regime will stay in power and ensure the stability of the country, at least for the next five to ten years. No one can say what China's political future holds after that'.

So, will Xi Jinping win his bet?

Will he ensure that the party keeps pace with a society in motion?

More importantly, will he succeed in linking neo-authoritarianism and technological innovation?

If he succeeds, China may well become the perfect 21st century dictatorship.

As Sinologist François Godement of the European Council on Foreign Relations has pointed out, 'Xi's Chinese Dream is a resurrection of Mao's totalitarianism, but with the benefit of technological tools that Mao could only dream of'.

'Communism is the Soviets plus electricity,' Lenin once said; a full century later, Xi could well reply, 'Chinese Communism is the party plus artificial intelligence and facial recognition'.

In any case, Xi has the determination, the political instinct, the culture and the career to achieve his ends. This was the conviction of Eric Li, businessman, political scientist and supporter of the regime, following the 19th Congress. '

Heedless of the Western media's predictions, which he believes to be erroneous, Li predicted in The Washington Post 'that Xi will indeed change China, and the world, for the better', because 'the party's ability to adapt to changing times by reinventing itself is extraordinary'.

One real threat remains, and I am not the only who sees it: in seeking to turn his country into a leading industrial power by 2049, for the centenary of the People's Republic of China, Xi is unleashing forces that may yet turn on him. A creative and innovating China may not be satisfied with the existing framework, and could in future support calls for political reform. But of how great a magnitude? The fate of the 'new emperor' depends, in part, on the answer.

Excerpted from Inside The Mind of Xi Jinping by Francois Bougon with the kind permission of the publishers, Westland Books.