With a BJP-backed government taking charge in Kohima, the prospects of the Naga Accord becoming a swift reality are considered bright.

Long before the Government of India appointed interlocutors to mediate with rebel Naga leaders, Sanjoy Hazarika had interceded with National Socialist Council of Nagaland chieftains Isak Chisi Swu and Thuingalang Muivah in Bangkok on then prime minister P V Narasimha Rao's behalf.

In this exclusive extract from his fascinating new book, Strangers No More: New Narratives from India's Northeast (Aleph), Hazarika explains the difficulties involved in negotiating an end to the nation's longest-running rebellion.

Yet, with the few insights that I have gained over time, as I look back at these basic demands, I realise that they reflected Muivah's political sharpness, honed over many years of dealing with governments and rival groups.

He had defined the core areas which would give advantage to the NSCN (I-M), weaken its political enemies and enable it to face New Delhi on a more equal playing field.

On this wicket, while it could not dictate the fate of the game, the NSCN could certainly influence the state of play by insisting on its own ground rules. On what I would call his basic platform of demands, he had ensured three major gains for his organisation and by interpolation for the Naga cause that he espoused.

- Political realism: This is Muivah's mantra -- political realism dictates that governments or stakeholders talk to the principal and strongest adversary, not the weakest or even the most loyal. It was a point he made time and again in our marathon discussions.

- Territorial expansion: The NSCN could not be limited to Nagaland and instead should be recognised as a major force that the government had to contend with in his home state of Manipur.

- Limiting the role of the Indian Army: The army, that holy grail of the Indian system, was to be pulled back from supporting his ethnic and political foes and asked to toe his line, no mean achievement for a man who was leading barely 3,000 armed followers at the time.

The formal political engagement between the Naga leaders and the Government of India is not yet over. After over two decades of talks, both sides are impatient to get it over and done with but a full agreement is elusive.

As always, the devil is in the details. There's an important point to be recognised -- without the powerhouse of the I-M, its armed forces backed by clear political determination, could the Nagas have come anywhere close to achieving what they have or are on the verge of securing?

The Government of India understands the power that flows from the barrel of a gun. The questions that the prime minister's representative and his Naga counterparts raise continue to be the same that successive negotiators have struggled with since the talks began on real issues in 2000 with K Padmanabhaiah, the second interlocutor:

Will the Naga army merge with Indian paramilitary forces?

Will a third Member of Parliament flag the concerns of the state and its people adequately?

Talking about flags, there is a demand for a separate Naga flag that won't go down well with either Parliament or other states, either of the region or across the country.

Why should, the argument goes, a state with a population of less than two million be rewarded with a special flag just for fighting the system and causing extensive bloodshed, apart from economic losses as well as social and political disruption?

Manipur, its Meitei population always sensitive to special deals with the Nagas and anything that might hurt its own interests, would probably be the first off the block to oppose this.

So would Assam and larger states like Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar.

The issue of the larger homeland of Nagalim, the dream of the Nagas to hold sway over swathes of Manipur, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, is just that, a dream. They have been told categorically that the government is not going to concede on this issue.

There is too much at risk here and the other states whose lands are being eyed are not going to take this lying down. The risk of civil conflict is very real with the states determined to exercise their right to protect their identity and oppose any claims.

In a future agreement, there will be a peace dividend too, with cash payouts to those who fought the Government of India; corporates wishing to invest in the state would receive handsome rebates, tax holidays and be given land on long lease in return for substantial fees, bringing cash into households and villages and resolving a perennial hurdle to investment in traditional communities like the Nagas.

Tribal groups hold tight control of property through a multi-layered web of individuals, clans and communities, seeing their identity in the soil they till or hold; this is a process and a fabric which is woven into their lives by myths as well as generations of families.

What is rarely spoken of is the myth of gender equality: For one, women are shut out of inheritance processes by traditional codes, except in a handful of families.

This was also one of the issues central to the movement for political representation by Naga women over the years, which peaked in the winter of 2016 and saw a furious blowback by dominant male groups which led to rioting, torching of public and private properties and intimidation. In firing incidents, at least two persons were killed in Dimapur.

IMAGE: Thuingaleng Muivah, left, and R N Ravi, the Government of India's Special Interlocutor for the Naga talks, exchange copies of the agreement the NSCN-IM reached with the government, August 3, 2015. Photograph: Press Information Bureau

For some time now, Muivah hasn't been running all rounds of the dialogue directly, as in the past. He comes for discussions when substantial issues are on the table. But otherwise, his trusted lieutenants V S Atem, the former army chief, and R S Raising, a smaller version of Muivah himself, both members of his Tangkhul tribe, hold fort. They know their leader's mind and consult him before and after the talks.

Age is beginning to tell on the legendary guerrilla who walked a thousand kilometres with a hundred fighters to Yunnan to win Chinese support. Muivah marched his men through Burma's leech-infested forests and over high hill ranges, evading deadly Burmese army patrols, snakes and malaria.

Isak Swu died in 2016 after suffering for a year with damaged kidneys and coming in for dialysis regularly at the Fortis Hospital in Delhi. Swu's passing was a stunning blow to his comrade of over fifty years, who had seen the summits and the valleys of life as a rebel.

'We were together for 52 years facing fire. Never have we had any disagreement over anything. Never did we doubt each other's intentions. I can't help but get emotional.'

The Sumi leader was, Muivah recalled, his closest friend and ally to whom he would turn for advice and guidance.

It was Swu's sudden deterioration in health in 2015 that provoked the government to sign a hastily drawn up framework with the NSCN leadership because, as Swu told a friend: 'I want to sign something before I go.'

He wanted this to be his legacy. But, alas, there wasn't much flesh on the framework.

Swu signed the brief statement from his bed in the intensive care unit at Fortis with his wife by his side, supporting him. It was this statement that was taken to R N Ravi, the interlocutor, and Muivah for their signature at the prime minister's official residence on August 3, 2015.

A year down the road, Swu was dead, having outlived the dire predictions of medical advice which pressured the hasty signing of the 'Framework Agreement', the talks were still on and the agreement was still secret because Muivah said that a separate flag and passport for the Nagas was not just a 'demand' but a right as the 'Nagas were never under Indian rule...'

'No, no. The understanding on shared sovereignty has been arrived (at) because the uniqueness of Naga history is recognised. We are not giving up on the demand of sovereignty,' Muivah said in an interview after the death of his colleague.

He also said that the framework had to be kept secret 'to save the course of the talks'.

The shared sovereignty idea, which surfaced in 2012 and has gained momentum since, is a part of official documents used during the negotiations.

It is, after all, a matter of interpretation. Many of the details from the nomenclature of the governor and chief minister, all part of the 31 points submitted by the NSCN a decade back, have been thrashed out and finalised.

What has been left unsettled is the explosive and interminable issue of garnering land from other states -- which no government in Manipur, Assam or Arunachal Pradesh can part with at the risk of inviting public wrath and political denouncement.

In addition, negotiators have got down to the nitty gritty about who would have the power to transfer deputy commissioners of districts and superintendents of police.

The shared sovereignty clause would enable the creation of a pan-Naga traditional body which would include all tribes located in different states but which would not have control over territory; it would be a cultural group that could rule on questions of custom, tradition and community.

Even this is a challenging proposition that is open to wide interpretation; those opposed to it will assert that it is an informal or back-door way of tackling the issue of land. It would have the impact of ethnic mobilisation, if not of territorial acquisition.

According to one account, Muivah told a large gathering at a resort owned by Chief Minister Neiphiu Rio on the edge of Dimapur town that 'the Government of India had accepted it as part of the competencies.'

He said the 'Pan-Naga Hoho' will be a statutory body with certain powers having separate budget, and very unique for the Nagas.'

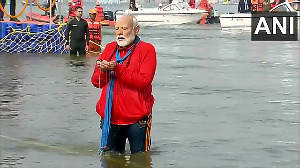

IMAGE: Prime Minister Narendra D Modi speaks after the signing of the Naga Accord, August 3, 2015.

Seated behind him are NSCN (I-M) supremo T Muivah, National Security Advisor Ajit Doval and Special Interlocutor R N Ravi. Seated to the prime minister's right are Home Minister Rajnath Singh and NSCN (I-M) leaders. Photograph: Press Information Bureau

The problem is that Naga 'customary law' is not written down or codified and hence is a tradition not a law.

Each tribe has its own codes and traditions, making codification even more complex. Each tribe disputes the capacity of the other to lay down the law.

How the Government of India and the NSCN will resolve this problem is anyone's guess.

It's like peeling an onion, layer after layer, with the accompanying tears.

What could happen is to turn to the tried and trusted way of all governments when faced with a problem: Appoint a committee of various individuals, well versed in the issue or respected by different sides (however, it would be close to impossible to get a set of consensual candidates which would be accepted by the NSCN).

That is a labyrinthine task. To provide an understanding of its vastness although we are speaking of a tiny state that has a population of barely 1.5 million, there are not less than 16 recognised tribes in Nagaland.

Of this list, 4 -- the Garo, Kuki, Kachari and Karbi, with a total population of about 100,000 largely in the Dimapur area -- are not accepted by some Nagas as 'indigenous Naga'.

So how do we define shared sovereignty? After all, to rephrase the Bard, what's in a word? It boils down to a matter of interpretation, not even of law, but of language.

Do you share my sovereignty or do I share yours? Or do we share each other's, rightfully, legally, dutifully, fully or in part, and for how long?

Till death do us part? But isn't shared sovereignty part of the way the Constitution has been written and how the Union of India is constituted -- a Centre and states in a federal structure?

Whether the states have a fair share or not is not the issue here. What matters is that even small states like Nagaland can make their own laws and impose taxes.

Nagaland is protected by Article 371A of the Constitution which says that no law passed by Parliament will be binding on the state unless it is passed by the state legislature.

This is unique, but it has been around for decades. Shared sovereignty is not a new concept. It is seen in the daily practice of Constitutional functioning in India.

It's a catchy phrase for an old process. Trust the mandarins in New Delhi to cook up something as sweet-sounding as this. But the taste can't be terrific and it has taken more than a year to digest.

Is it all about a Republic within a Republic? Or is there something more?

It boils down to a simple question of how we live with others. This is especially challenging in a predominantly rural society where 80 to 90 per cent of the population lives in villages where groups and individual family units depend on each other for help and interaction, both economic and social.

One of the byproducts of urbanisation, structured living -- with guilds, religious and State origin groups as well as ethnics dominating specific neighbourhoods -- is still a slow phenomenon.

The issue of living peacefully with one's neighbours, whether close or distant ones, is an issue that engaged the ancient Romans and Greeks, the Indian and Chinese civilisations as

well as the Native Americans, Africans and the Aborigines of Australia.

It is that simple, yet so critical and difficult.

Excerpted from Strangers No More: New Narratives from India's Northeast, by Sanjoy Hazarika, Aleph, 2018, with the publisher's kind permission.

© 2025

© 2025