In the crazily complex cauldron that is India, where caste, community, class and cash are just the primary ingredients, no one has yet come up with a fool-proof method to ascertain how voters make up their minds, on which button to press, in the privacy of their 'confessional' booths, notes Krishna Prasad.

After watching Indians at a polling booth and failing to read their mind on which way they were inclined to vote, James Reston, the late executive editor of The New York Times, grandly concluded that an election was a secret communion between a voter and democracy -- it is sacrilegious to pry.

Now, where 'Scotty' Reston wrote this is unclear because you cannot find it in his memoirs, Deadline. And a Google search shows the same writer quoting the line on three different platforms over 20 years. No one else. Still, it is a fine quote, and even if the NYT legend didn't say it, he ought to have said it.

But Reston does say something like this about the Truman-Dewey faceoff in 1948.

Based on early trends, the Chicago Daily Tribune's veteran correspondent Arthur Henning -- who had correctly predicted the winner in four out of five presidential contests in the previous 20 years -- reported that the Republican challenger Thomas E Dewey had won an upset victory over incumbent President Harry S Truman.

'Dewey Defeats Truman', screamed the banner headline in early editions of the newspaper.

Wrong.

After all the numbers came in, it was the other way round.

Truman beat Dewey.

James Reston, who got a 'D' grade in his journalism course, writes: 'I felt that it was somehow right that we were wrong; that this great act of decision by millions of people was intensely private; and that we were properly punished by presuming to guess how the people would vote.'

***

That gigantic journalistic screw-up 70 years ago, which would have been filed under 'fake news' today, has never stopped anybody -- journalists, psephologists, newspapers, TV channels, academics, analysts, astrologers, think-tanks, bankers, nobody -- from peeping into the 'secret communion'.

Praveen Chakravarty of the Congress data analytics department has put out a tweet that 80% of all published exit polls since 2014 have turned out to be wrong. Still, everybody wanted to know who's winning #GeneralElections2019, a couple of days before the actual results come out.

Even if it is wrong.

Is it really going to be 177 for NDA as an 'India Today' screengrab showed? Or, is it 234 as 'independent psephologists' predicted for IANS?

Will BJP get 50 seats in UP as Subramanian Swamy says? Or, is it going to be a 'rout' as the Web site anthro.ai that uses Artificial Intelligence predicts?

A hung Parliament as Swaminathan Aiyar feels, or an 'overwhelming majority' of 300 for the BJP as a traders body claims?

And who is this Salil Shetty who is giving 287 for Congress and its allies?

The simple truth is no one knows, for sure.

In the crazily complex cauldron that is India, where caste, community, class and cash are just the primary ingredients, no one has yet come up with a fool-proof method to ascertain how voters make up their minds, on which button to press, in the privacy of their 'confessional' booths.

Any guess can be right or wrong; sometimes even right and wrong. Any wonder that as respected a landscape artist as the Centre for Study of Developing Societies has not got a single exit poll right since 2014?

But let no one say no one has tried.

Jawid Laiq was 34 and a reporter at The Indian Express in Delhi, when he arrived in Allahabad with his soon-to-be wife Bharti Bhargava, also an Express reporter. It was February 1977. Indira Gandhi had called off the Emergency after 21 months and announced fresh elections, confident that she would be returned to power again.

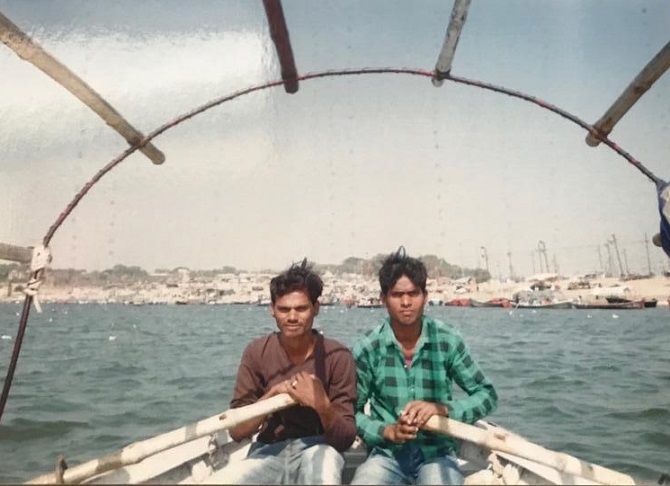

"We hired a boat and went to the 'Sangam', the confluence of the Ganga, Yamuna and the mythical Saraswati rivers. At first, when we asked how they were going to vote, the boatmen and the passengers feigned ignorance: 'Hum to jahil hain.' After a while they opened up and said they would never vote for Indira, and trotted off the many brutalities inflicted on common folk like them," recalls Laiq, now 76.

Indira Gandhi lost and lost spectacularly, heralding independent India's first non-Congress government.

'The words of the crowd proved to be a more accurate forecast of the electoral battle than all the complex opinion polls engineering by various organisations,' Laiq wrote later in his book Maverick Republic.

That experience has proved to be the inspiration for a 42-year-old personal exercise.

For eight elections running, Jawid Laiq, who after the Express went on to work for the Economic & Political Weekly in Bombay and Amnesty International in London, has made his own private pilgrimage to the 'Sangam', where not just the waters, but millions from every part of the country converge for a dip, to feel the proverbial pulse.

Each time he has reported the 'hawa', the straws in the wind, for publications ranging from the Hindustan Times to Outlook. And each time, he has had far greater success in judging the direction of the election than pundits and psephologists with sophisticated 'tools'.

"The humble mallahs (boatmen) row thousands of yatris every day. The devotees and their families talk; the boatmen quietly listen to the chatter. This happens through the year. The mallahs have no axe to grind. They can see which way the breeze is blowing," says Laiq.

Elections like the 1984 one after the assassination of Indira Gandhi were obviously too easy to gauge. But it is the on-point accuracy of the complex ones, like the 2004 election after the 'India Shining' campaign of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, or the 2014 poll at the peak of the "Modi wave", that underlines the wisdom of the crowd.

The 2017 elections in Uttar Pradesh, the only assembly election Jawid Laiq has tested at the 'Sangam', is a particularly good example.

"After demonetisation, I was convinced people would be against Narendra Modi," says Laiq. "I was surprised. I met pilgrims from seven districts of UP and they all said they would vote for the BJP. 'Is mein kya hain? Unka sab paise gaye (what's there in this, they all lost their money),' the yatris said, exhibiting what the Germans call 'schadenfreude' (pleasure at the pain of others even if it pains you)."

Result: When the BJP walked away with 325 seats in a House of 403, Jawid Laiq was probably the only journalist in Lutyens Delhi who could have said, 'Didn't you read what the Nishads (boatmen) said in my story?'

***

Admittedly, you can't make too much of this quaint, quirky, even quackish personal journey. Unlike actual opinion polls with elaborate questionnaires, statistical models and 'margins of error' built into them, what Jawid Laiq catches at the 'Sangam' is a general trend, not a precise number.

But there is a method to it, even if it is all too mundane.

He hires a boat and when he reaches the 'Sangam', he hops over from boat to boat. If you have seen him, it is easy to visualise the soft, avuncular man standing at the top of a ramshackle boat and shouting in the breeze -- 'Aap kidhar ke hain?', 'Kya karte hain?' -- before introducing himself, 'Hum patrakar hain, Dilli se aaye hain'.

If he suspects the yatris are South Indians, the transaction is in English.

The people Laiq meets at the 'Sangam' -- the bus owner from Andhra; the landlord from Punjab; the retired government officer from Karnataka; the kirana store owner from Maharashtra; the farmer from Madhya Pradesh -- are a far cry from those that populate TV studios, and that probably accounts for the overall humility of the claim.

"I ask very basic questions. 'Who did you vote for? Why? What is the general mood in your part of the country?' I carry a big note pad and take notes so that they know I am serious. I don't make any suggestions, I never prompt them for an answer. I spend a couple of hours doing this in the mornings, a couple of hours in the evening, for two or three days. About a dozen boats each day," says Laiq.

That done, Laiq visits a couple of villages near the Bamrauli airport in Allahabad -- the Brahmin-dominated Barwah; the Dalit-dominated Bhagwatpur -- and meets a set of people he has met since 1977. A dhobi and his wife. The retired food inspector.

Along the way he meets the ice seller on Noorullah Road.

"There is something aesthetic about the 'Sangam' exercise. All the colours of India at the holy confluence. The notepad dampened by the splashing waters of the Ganga," he says. "The practical wisdom of the village peasant, labourer and artisan is in stark contrast to the convoluted, deceitful and self-serving ramblings of the metropolitan sophisticate."

***

Like those who will stick their necks out for a living on May 19, Jawid Laiq is worried of getting it wrong although he has got seven of them right. He is in dread of the 2019 election, which, as he points out, came too soon after the Kumbh Mela, when the boatmen would have had their reasons for bias.

He went to the 'Sangam' after the fifth phase of polling, and has come back despondent.

"If the hysterical and aggressive personality cult howling for Modi that seems to be apparent in most regions of the country -- except perhaps in the southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Telangana and Tamil Nadu -- annoints him as prime minister with an enhanced majority, the country is heading for a rough ride with so much power in the hands of one forceful figure," he wrote on The Wire.

Privately, Jawid Laiq says the boatmen are suggesting that the BJP could end up with more seats than in 2014, perhaps more than 300 as BJP President Amit Anilchandra Shah has been saying.

'Modi beats Rahul', is the headline a latter-day Arthur Henning would have shot off before the polling had closed.

But who knows if, after the seventh phase, it is the other way round?

'Rahul beats Modi'.

When the final results come in on May 23, even Jawid Laiq, who correctly predicted trend in seven elections in 42 years, will have reasons to be on edge.

If Laiq's surmise turns out to be right, there is nothing to be embarrassed. If it doesn't, it would be useful to remember 'Scotty' Reston: 'I felt that it was somehow right that we were wrong; that this great act of decision by millions of people was intensely private; and that we were properly punished by presuming to guess how the people would vote.'