'Galbraith had a powerful ally in Washington -- not as blunt and direct as the ambassador -- but committed to see Krishna Menon go.'

'This was President Kennedy himself.'

A revealing excerpt from Jairam Ramesh's brilliant new book, A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of V K Krishna Menon.

V K Krishna Menon was India's defence minister when China went to war with this country in October 1962.

The Indian military was routed by the Chinese, a military debacle that was attributed to Krishna Menon's poor leadership at the defence ministry.

Congress and Opposition politicians asked Nehru to sack Menon and take charge of the defence ministry himself.

Pressure was also building on the prime minister from a different quarter, as Jairam Ramesh discloses for the first time:

V K Krishna Menon came back to India in the first week of October 1962. On October 5, 1962, Nehru wrote to the army chief, General P N Thapar:

I have just received a letter from the President which runs as follows:

'I am surprised and pained to see this morning a press report [in the Times of India] that a special task force was being sent to NEFA charged with pushing the Chinese out. Such secret military information is not given out. It will give previous warning to the other and endanger the lives of men.'

I was myself greatly surprised and distressed to see the report in the press this morning ... I am having an investigation made as to how this leakage in the press took place...

We don't know what that investigation revealed, but what we do know is that the same day Krishna Menon got a press note issued officially. The note denied that a special task force had been created to deal with the Chinese intrusion in NEFA, but acknowledged that 'reorganisation of the defence arrangements in the area had been under consideration for some time...', which had led the Indian Army corps in north-east India to be split into two units: One to be led by Lieutenant General B M Kaul, to be responsible for the border facing China, and the other to be led by Lieutenant General Umrao Singh, to be responsible for Nagaland and the border with East Pakistan.

It did not escape attention and comment that it would be the 'first time that Lt General Kaul will be holding a senior command in an operation theatre'. Many years later Major General D K Palit, who was then director of military operations, would reveal that Kaul himself had been the source of the leak of his assignment that had so infuriated the President, prime minister and defence minister.

History will always judge Nehru, Krishna Menon and Thapar most unkindly for Kaul's NEFA appointment. One view is that Krishna Menon and Thapar had orchestrated it, but Nehru had supported them fully.

The situation, from India's point of view, worsened by the day with territory and men being lost -- the latter in substantial numbers. India's defence preparedness and lack of military equipment stood woefully exposed.

On October 25, 1962, the man who had first made Krishna Menon an MP nine years earlier spoke out and echoed the sentiments of a very large number of Congressmen themselves.

C Rajagopalachari suggested that the 'present Defence Minister should be relieved and the Prime Minister should take up the responsibility of the country's defence himself by calling on a suitable General or ex-General to assist him as Minister of State'.

A state of national emergency was declared on October 26, 1962, and urgent requests were made to the US, the UK and Canada for urgent military supplies.

On October 29, 1962, Krishna Menon made a flying visit to Leh and Srinagar to boost the morale of the troops while in New Delhi his ministry put out an official denial that he was resigning.

But on October 30, 1962, Krishna Menon would send in the first of his three resignations to Nehru.

Just as Krishna Menon was resigning his senior colleague and minister without portfolio T T Krishnamachari also wrote to Nehru:

'Whatever your views might be, and ultimately they count, your colleague, the Defence Minister, has demonstrably showed his utter incapacity to act. I am told you think that he is the most intelligent man inside and outside the Cabinet. It might even be true. But intelligence in the abstract is of no use to anybody, least of all the possessor... The Defence Minister's methods of going about things will not yield results. You cannot forget the fact that the Defence Minister is persona non grata in most quarters, or at least in quarters that count for us at the moment...'

Krishnamachari then went on to speak of 'Krishna Menon and his minions' and their incompetence, and gave Nehru some suggestions for improving defence management. He ended the letter with great anguish:

'Please do something: Something to prevent this atmosphere of a Greek tragedy deepening.'

On the evening of October 31 1962, an official announcement was made that Nehru was taking over as defence minister and that Krishna Menon would continue as minister of defence production.

That morning, Krishnamachari met Nehru and complained that his phone was being tapped. Nehru was taken aback and promptly asked the home minister and the director of the Intelligence Bureau, B N Mullick, to conduct an inquiry. Krishnamachari would write to Nehru on 2 November 1962:

'It was just like you to write so promptly regard to my complaint about the tapping of my telephone. The DIB [Mullick] saw me in this connection today. The subsequent information that I got is that the tapping was done at the instance of the military authorities and the persons doing the tapping were withdrawn at 8 o'clock on the night of the 31st October, presumably because of the change in the direction of the Defence Ministry -- though it is asserted that no real change has taken place.'

Krishnamachari was alluding to an assertion reported to have been made by Krishna Menon. As soon as he took over as minister of defence production he flew to Tezpur in Assam, which was the headquarters of the north-east army corps. He addressed a public meeting there which, by all accounts, was 'mammoth'.

If he had done just that he would not have got into further controversy, but then he would not have been Krishna Menon. The Hindu carried this news on November 2, 1962 from Tezpur:

'Mr V K Krishna Menon said in Tezpur today that Prime Minister Nehru's taking over the Defence portfolio from him was 'merely a move to bring more strength into the administration'. He said the decision had not come to him as a surprise... Replying to a question whether the changes that had come into effect today [November 1, 1962] had been under consideration for some time, Mr Menon said 'yes'.'

'He added, however, 'Nothing has changed. I am still a member of the Cabinet and I am still sitting in the Defence Ministry'.'

That very morning, President Radhakrishnan conveyed his displeasure to Nehru, sending him a clipping from another newspaper. The Prime Minister shot back at once:

'The Statesman cutting is not quite correct. Probably Krishna Menon said something casually which does not give the right impression. I am in charge of Defence and am dealing with it myself directly and am going to the Defence Ministry daily. Krishna Menon has got a limited responsibility in regard to production matters which are under the Defence Ministry...'

Technically, Krishna Menon was right, but it was hardly the thing to say under such tense circumstances, especially when his exit as defence minister had been widely welcomed.

On his return to the capital he denied having made any such statement, but the damage had been done. His critics, both within the Congress and outside, now bayed for more blood.

November 7, 1962, Krishna Menon sent not one, but two letters of resignation. This may have been prompted by Nehru.

Subsequently, Nehru forwarded Krishna Menon's resignation to the President:

'I enclose copies of two letters I have received from Shri Krishna Menon offering his resignation from Government. I have already shown you these letters. I propose to write to him accepting his resignation after I learn your wishes in the matter. These wishes have been conveyed to me orally by you already. But I would be grateful if you would kindly repeat them in writing.'

This was a curiously worded letter, and what it implied was to be highlighted 27 years later by Radhakrishnan's authoritative biographer, his son, the eminent historian S Gopal, who was also Nehru's pre-eminent biographer. Gopal would write:

'In other words, Nehru wished to leave the responsibility for the final decision to the President, with perhaps a subconscious hope for at least delay in, if not abandonment of, Menon's departure. Certainly the recognised procedure of the President acting on the advice of the prime minister was reversed.'

Radhakrishnan in his reply did not communicate his wishes, but took a firm decision:

'As you said, in the circumstances, for the sake of national unity we have to accept Shri Krishna Menon's resignation with regret. On hearing from you a formal announcement will issue from the Rashtrapati Bhavan'.

Till his death Krishna Menon would continue to say that he had not been 'sacked' or 'fired' or 'asked to go'. He would insist that he had resigned. The evidence does support this fine distinction he drew on the manner of his departure as defence minister. But it is also true that many Congress MPs were challenging Nehru.

Pressure from within the Congress party apart, there was another factor at work that made Krishna Menon's departure inevitable. Right from the time Nehru asked for American military assistance, Krishna Menon was a marked man.

There had always been mutual antipathy between him and the US ambassador in India, John Kenneth Galbraith, which had been exacerbated after Goa's liberation. Galbraith seized this opportunity to start a campaign for Krishna Menon's ouster. He was to later discuss this episode in his memoirs that appeared in 1969.

But Galbraith left out crucial details of what he had done and how he had ensnared the British and the Canadians in his 'plot' to get rid of Krishna Menon as a condition for receiving military assistance.

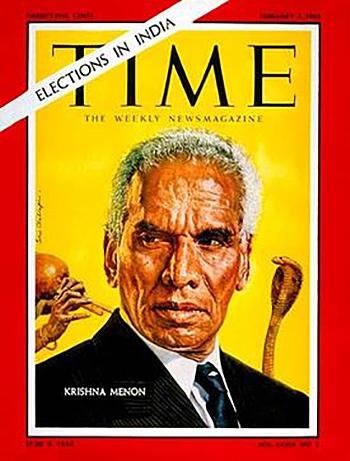

IMAGE: V K Krishna Menon on a Time magazine cover.

IMAGE: V K Krishna Menon on a Time magazine cover.

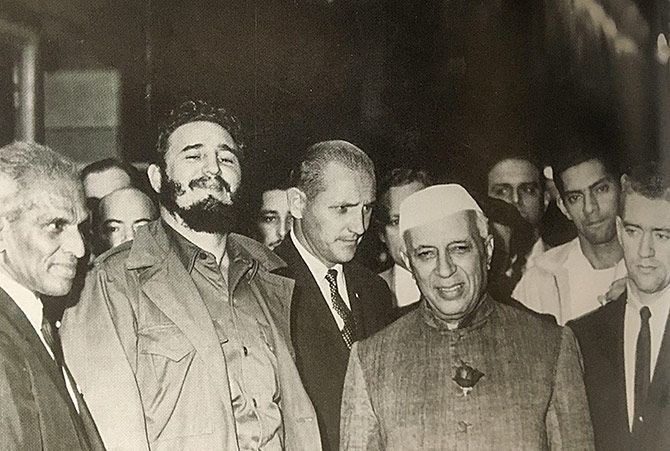

Galbraith had a powerful ally in Washington -- not as blunt and direct as the ambassador -- but committed to see Krishna Menon go. This was President Kennedy himself. He had met with Krishna Menon a year ago at the White House but now the situation had changed completely.

On October 26, 1962, he met with the Indian ambassador to the US, B K Nehru. The official US record of that meeting on Krishna Menon was anodyne, but in reality, what Kennedy had told the Indian ambassador was this:

'The President then said that, on a purely personal basis between himself and the Ambassador, and not speaking governmentally, he wished that Krishna Menon were not Defense Minister.'

In that conversation, Kennedy had also asked the Indian ambassador whether 'Krishna Menon would continue to be the Grand Moghul presiding over the American military supply line'.

During the war, Krishna Menon had tried, till the very end, to avoid seeking military help from the US. On October 27, 1962, Nehru wrote to him:

In the course of a letter from the President [Radhakrishnan] to me he says: 'USA Ambassador Galbraith was here last evening and said that the USA were willing to supply us with any equipment we need, but that they had not been asked. We should not lose time in getting equipment from any source. I entirely agree with the President.'

The same day Carl Kaysen, a Kennedy aide, sent an 'Eyes Only for Ambassador Galbraith' telegram from the White House:

'... We here agree with your assessment of the value of getting Menon out . . . We again urge the importance of avoiding the slightest appearance of US initiative and responsibility in removing Menon. Our efforts with Ayub [Ayub Khan, President of Pakistan] will be such as to prepare the way to take advantage of Menon's disappearance without requiring it as a condition for forward motion...'

Parliament convened on November 8, 1962. Normally, a minister who has resigned is allowed to make a personal statement. This is what C D Deshmukh, Nehru's finance minister, had done in July 1956. Deshmukh had used that opportunity to lash out at Nehru and some of his colleagues, who had all heard him in silence. But Krishna Menon chose to keep quiet. He made no such statement.

In any case, it was hardly the time for him to speak since there was only a pause in the war. Predictably, his resignation was widely welcomed both in India and abroad.

The heat was off Nehru, who emerged stronger after Krishna Menon's departure. But Krishna Menon got hundreds of letters of sympathy as well, including from those who had been at his receiving end.

Excerpted from A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of V K Krishna Menon, by Jairam Ramesh, Penguin, with the author and publisher's kind permission.

© 2025

© 2025