'As we finished the operations on 15th December, the word was already in that the Pakistanis were capitulating and some kind of peace and surrender was in the offing.'

Air Commodore Ram Mohan Sridharan -- 'Doc' Sridharan, as he is popularly known in the Indian Air Force -- was commissioned as a helicopter pilot in the IAF in June 1969.

A young helicopter during the 1971 War, Air Commodore Sridharan tells Air Commodore Nitin Sathe how IAF helicopters ferried troops and guns into then East Pakista, which played a crucial role in the Surrender at Dacca.

The third segment of a fascinating four-part feature:

- Part 1: How IAF choppers helped General Sagat liberate Bangladesh

- Part 2: 'The boys were so fired up to fight the enemy'

The first-day missions for Doc Sir had seen a fair amount of adrenalin rush and now he was ready and confident for subsequent missions.

The unit was now tasked to carry out further troop insertions across the Meghna river to tighten the noose around Dacca and force a surrender at the earliest.

This is the first time that the Indian Air Force's Helicopter Fleet carried out Special Heliborne Operations (SHBO) by night.

Now that the crews had gone through a few, their confidence levels were high and they were rearing to go for more missions.

SHBO by night requires much more piloting skills and has its risks especially when being flown in dark nights without the moon.

Navigation is difficult and the stress levels for making the time over the target as well as making the correct Drop Zone are high.

The makeshift grounds from where the helicopters were taking off and landing in enemy territory had no aids but for a few 'goosenecks' and 'glim lamps' that were placed around the landing ground.

"These had to be made ready by our own troops available on the ground. Also required was some degree of protection of the area from enemy attack. As the troops kept coming in, the security became less of a problem," remembers the IAF veteran.

"Despite all this," he adds, "we did suffer a few bullet hits over the next few days. Luckily for us, these were minor injuries to the aircraft and our ground crew did an excellent job of keeping all the 10 helicopters serviceable for the missions."

Goosenecks are oil-filled lamps with large wicks which can burn for a long time. But with the rotor downwash, these tended to extinguish and as the first of the helicopters landed, it was not possible in operations to get them going again.

Secondly, the flights were undertaken without external lights and it became difficult for the trailing aircraft to maintain formation.

Luckily for the crew undertaking these missions, the weather was good and the moon shone bright which made things a bit easy.

Glim lamps are little portable battery-operated lights that can barely be seen from the air.

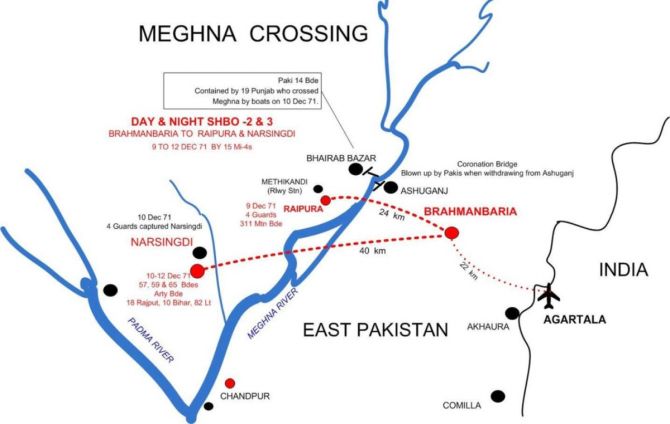

The helicopters were positioned from Agartala to Brahmanbaria in East Pakistan now held by our troops.

In phase 2 and 3 of the operations, the helicopters were required to lift troops from Brahmanbaria to Raipura and Narsingdi across the Meghna river.

The distance to the LZ (Landing Zone) was between 25 to 40 km and meant flying over enemy territory for about 30-35 minutes," Air Commodore Sridharan recalls.

"While we flew at treetop level most of the time, the threat from small arms could not be ruled out," he remembers. "We also had to be careful while flying over water bodies since the Pakistanis were known to have gunboats patrolling the river."

Sorties began on the morning of December 10, 1971 for phase 2 and 3 of the operations and continued non-stop till December 12th.

"In three days we had got across the Meghna river 2,856 troops and delivered almost 113,000 kgs of military hardware to help our boys fight the war to Dacca," the air commodore recalls.

The artillery's wheeled guns were the most problematic to carry. They took a long time to load and offloading required ramps to be put at the rear of the helicopter to wheel them out of the cabin. This meant more time on the ground in enemy territory.

In Doc sir's recollection, "Our crew and the Army guys trained on the job and were very good. They developed excellent understanding amongst themselves and ensured that we spent the least time on the ground."

Air Commodore Ram Mohan Sridharan.

"For some reason, I was always given the artillery guns to carry and sometimes had to split from the formation and get back to base alone!" the IAF veteran exclaims.

"And yes, the locals (Bengalis in then East Pakistan) came in large numbers to help us offload. They were willing to brave the bullets for a good cause!"

"On the way back, we always had injured soldiers to be carried to safety. We heard from them how the retreating Pakistanis weren't sparing the locals. Besides the looting and mass rapes being carried out, the Pakistanis were on a killing spree," the air commodore remembers with clarity events of 49 years ago.

A large number of Mukti Bahini -- the rebel Bengali army in then East Pakistan -- soldiers had been found with their hands tied behind their backs and shot in their heads. "The Pakistanis were not very kind to our soldiers too. Similar treatment was meted out to some of our guys," the air commodore reveals.

In the fourth phase, operations shifted south to a place called Daudkhandi. "From here we were to carry troops and equipment to Baidya Bazar, just south of Dacca," he says.

"On the 14th and 15th December, we carried about 2,400 troops and 73 tons of equipment into the area."

"Once again, the operations went off very smoothly and we were happy that barring a few bullet holes, we were all in one piece to take the war further."

"As we finished the operations on 15th December, the word was already in that the Pakistanis were capitulating and some kind of peace and surrender was in the offing."

"We had helped the army tighten the noose around Dacca. There was no way that the Pakistanis could give us a fight anymore or so it seemed," he says.

"Our task force commander Group Captain Chandan Singh came over and gave us all a pat on the back for a job well done."

"'The war will now be fought on the streets of Dacca. Get ready for some action from now on. These are going to be dangerous missions and we should be ready for the worst. So, keep your wits about you, don't get overconfident and get ready for some hot action!'," he said, briefing us.

"Thankfully, this was not to happen. The Pakistanis agreed to an unconditional surrender which was to be held at the Dacca racecourse on the evening of December 16,1971."

"We breathed a sigh of relief. War had taken a fair amount of toll on our nerves and we longed for some relief. We were glad we had ended on the winning side and there was a lot to cheer about."

"Colonel Behl of the Artillery Regiment fired the first shot into Dacca garrison on the 13th December from one of the guns dropped by us."

"The impact of the subsequent shelling was too much for the Pakistanis and their end was almost near."

During the entire operations, the IAF lost one helicopter, but its crew were safe. The loss was not due to enemy action.

"While returning to Kumbigram from the operations area for major servicing, one helicopter had an emergency of transmission failure light coming on and the crew landed in the fields."

"While they were switching off the machine, a fire in the engine compartment was noticed which quickly engulfed the machine. While the crew ran to safety, the aircraft was completely gutted," the IAF veteran remembers.

"You see, we had been landing on unprepared grounds for a fair amount of time. A lot of dried grass was being sucked into the engine compartment. Although it was being cleaned before every flight," the air commodore adds, "I suspect that the fire was due to some of this grass igniting due to the hot engine which quickly spread; and in the absence of any firefighting close by, we had to lose the machine".

"Our technical and logistics crews did an excellent job through the short duration of the war," he says. "The serviceability state was kept high and we never had an instance of a machine not being available for flying."

"The fuel and oils, which are expended quite rapidly, had to be brought to the forward operating grounds and supplied to us in time."

"It was time when a lot of innovations and jugaad were done so that we achieved our task."

"For quick refuelling of the aircraft, the gasoline was brought in drums and we used to put the booster pumps of the aircraft itself for rapid refuelling."

"The bullet holes had to be fixed before every flight and also the thorough check-up of the aircraft was required so as to see to it that no vital component had been damaged under the skin."

Air Commodore Nitin Sathe retired from the Indian Air Force in February 2020 after a distinguished 35 year career.

The author of three books, you can read Air Commodore Nitin Sathe's earlier features here.

© 2025

© 2025