'India should today tell China to provide proper facilities in Minsar for Indian yatris visiting Mt Kailash,' says Claude Arpi.

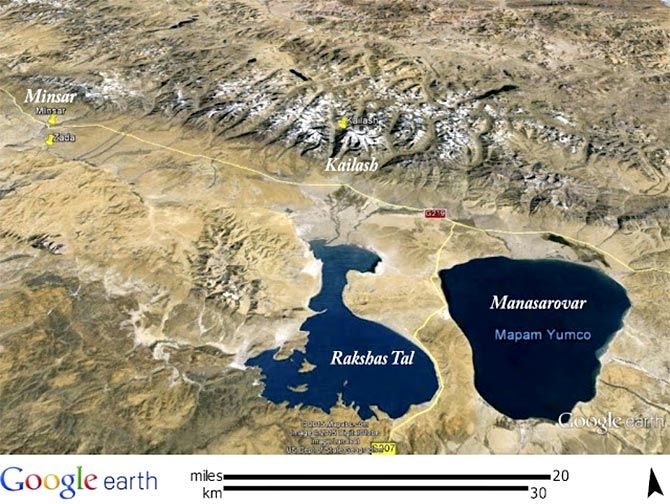

IMAGE: A Google Earth capture of the Indian village of Minsar in Tibet.

At his monthly press conference, Senior Colonel Wu Qian, the spokesperson for China's ministry of national defence, answered a question about China maintaining a high military presence close to the Doklam area.

'Dong Lang area is Chinese territory, and, therefore, we will decide the deployment of our troops on our own,' Wu said.

Beijing is always quick to claim territory which is not its own; in the present case, it belongs to Bhutan.

It is probably not in Indian genes to claim other nations' territory; but worse, in some cases, India has been unable to claim its own territory.

Here is the story of a small parcel of India in Tibet: A village called Minsar.

For centuries, the inhabitants of Minsar, although surrounded by Tibetan territories, paid their taxes to the kingdom of Ladakh.

During the 19th century, when Ladakh was incorporated into Maharaja Gulab Singh's state, Minsar de facto became a part of Jammu and Kashmir state.

In October 1947, after Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession, Minsar became Indian territory. This lasted till the mid 1950s.

John Bray, the president of the International Association of Ladakh Studies, who wrote about the Bhutanese and Indian (Minsar) enclaves in Tibet, noted: 'Both sets of enclaves share a common origin in that they date back to the period when the kings of Ladakh controlled the whole of Western Tibet.'

'The link with Bhutan arises because of the Ladakhi royal family's association with the Drukpa Kagyupa sect,' Bray pointed out.

This school of Buddhism, different from the Dalai Lama's Gelukpa, has been influential in Ladakh and Bhutan for centuries.

The rights to the small town of Minsar were inherited from the Peace Treaty between Ladakh and Tibet signed in Tingmosgang in 1684.

Besides the confirmation of the delimitation of the border between Western Tibet and Ladakh, the Treaty affirmed: 'The king of Ladakh reserves to himself the village of Minsar in Ngari-khor-sum (Western Tibet).'

For centuries, Minsar was a home for Ladakhi and Kashmiri traders and pilgrims visiting the holy Mount Kailash.

A report of Thrinley Shingta, the 7th Gyalwang Drukpa, head of the Drukpa school of Tibetan Buddhism, who spent three months in the area in 1748, makes interesting reading:

'Administratively, it is established that the immediate village of Minsar and its surrounding areas are ancient Ladakhi territory. After Lhasa invaded West Tibet in 1684, it was agreed and formally inscribed in the Peace Treaty between Tibet and Ladakh, signed in 1684, that the King of Ladakh retained the territory of Minsar and its neighbourhood as a territorial enclave, in order to meet the religious offering expenses of the sacred sites by Lake Manasarovar and Mount Kailash.'

This arrangement continued for the following nearly three centuries.

I recently came across a fascinating report sent by the special officer appointed by the government of Jammu and Kashmir who visited Minsar in the summer of 1950.

Just after he had left, the external affairs department in the J&K prime minister's secretariat wrote to the ministry of states in Delhi to explain the circumstances of the special officer's trip to Western Tibet.

The communication from Srinagar states: '...the State Government have already deputed a Civil Officer, Mr N Rigzen Ghagil Kalon, with an escort of armed police to visit Minsar village. From the last report received from Mr Kalon it appears that the Tibetan Government have put restrictions on people entering their territory with arms.'

'His report further indicates that he reached Rudok on 3rd June, 1950 leaving the police escort behind at Chuchhol (Chushul) a border village on the side of the Jammu and Kashmir State.'

'At Rudok the Civil Officer was informed by the Tibetan officials that he could proceed to Minsar without an armed escort... the Civil Officer along with some constables in civilian dress and without arms are on their way to Minsar.'

Kalon was permitted by the Tibetan authorities to visit Minsar. He had to, however, follow Lhasa's rules which stipulated that no arms could be carried by foreigners in Tibetan territory.

Lhasa had no issue with India's sovereignty over the village near Mount Kailash.

On September 13, 1950, after his return to Srinagar, Rigzen Ghagil Kalon sent a report to the J&K government and Delhi.

It is worth noting that a few weeks later, Chinese troops would invade Western Tibet; the fate of the Indian village would then change.

Kalon mentions the village of Demchok, 'the last boundary of the Tehsil Ladakh from which begins the Chhangthang Plateau of Lhasa Tibet.'

'The route from Demchok to Minsar passes through Gartok which is the headquarters of Garpons (governors of Western Tibet),' he further explains.

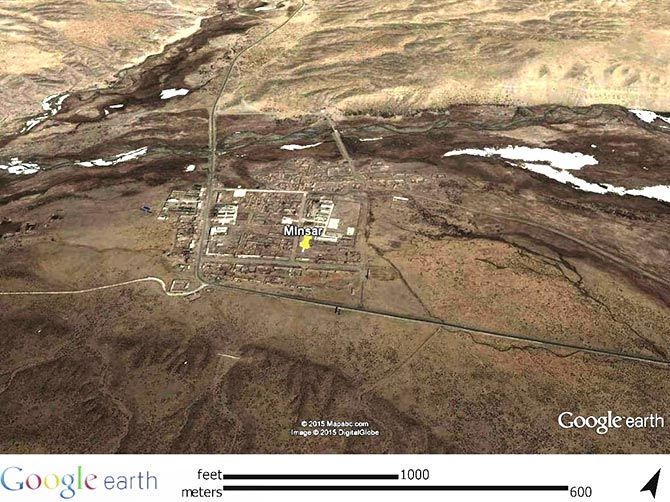

The report describes the Indian village: 'Minsar is situated to east of Gartok and about 32 miles west of Mount Kailasas (Kailash). It is a broad valley with vast plains in it. There are 68 families with 271 souls of which 120 are males and the rest females and are all adherents of Buddhism.'

'The entire population depends on livestock which is the only source of subsistence and deal in the trade of sheep, wool, and pashmina. The economic condition of the people is neither much satisfactory nor so much frustrated.'

Kalon then recounts his meetings with the Garpons at Rudok. They discussed the issue of 'taking my Police Constables to Minsar and installation of a Chowki there. They told me that it would create some consternation in Minsar and its suburbs if the whole quota of six constables along with rifles were permitted to accompany me and so two constables were permitted to accompany me and the rifles were kept concealed under our saddles.'

The governors had no issue with the J&K representative visiting Minsar, only arms were not permitted.

'I directed the other four constables to stay at Demchok,' Kahol notes. Incidentally, Demchok, today claimed by China, was then undisputedly part of Ladakh tehsil.

During his stay in Minsar, the special officer interacted with the headmen and the population.

'They expressed that this attitude of our government had extremely disgusted them and they wanted an immediate redress before payment of revenue.'

'No help was extended to them at the time of the incursion of the Kazaks (in 1941, tribes from Kazak invaded Western Tibet). The Kazak raid had wholly ravaged their villages and looted and ruined their monasteries.'

'The figures of personal properties of the people leaving aside the monastic wealth were cash Rs 25000/-, horses 140, yaks 404, and sheep 4,889.'

Another complaint was that they had to pay double taxation, to Srinagar and to Lhasa.

'The people are subjected to the payment of puggur dues (goods sold by the Tibetan officials to their subjects at exorbitant prices) which is a gross injustice of the Tibetan government on the people.'

Minsar's residents requested that 'an official from our Government should stay there annually at least for three months in summer who will look after the general situation of the place.'

The conclusions of the special officer, as well as of the political officer in Sikkim overall in charge of Tibet's affairs was this should be possible to satisfy the inhabitants of the Indian enclave in Tibet.

The situation remained the same in the following years.

IMAGE: Another Google Earth capture of the Indian village of Minsar in Tibet.

In 1953, wanting to sign his Panchsheel Agreement with China, Jawaharlal Nehru decided to abandon all Indian 'colonial' rights inherited from the British.

Though he knew that the small principality was part of the Indian territory, he felt uneasy about this Indian 'possession' near Mount Kailash in Tibet.

Nehru was aware that Minsar had been providing services to pilgrims visiting the sacred mountain and the holy Manasarovar lake, but he believed that India should unilaterally renounce her rights as a gesture of goodwill towards Communist China.

He instructed the diplomats negotiating the Panchsheel accord in Beijing: 'Regarding the village of Minsar in Western Tibet, which has belonged to the Kashmir State, it is clear that we shall have to give it up, if this question is raised.'

'We need not raise it. If it is raised, we should say that we recogniSe the strength of the Chinese contention and we are prepared to consider it and recommend it.'

Minsar was even not discussed during the talks for the Tibet (also known as Panchsheel) Agreement.

It means that the fate of this enclave was never negotiated or settled. It remains so today.

Nehru's perception that old treaties or conventions could be discarded or scrapped greatly weakened the Indian stand in the 1950s (and later when China invaded India).

Nehru's wrong interpretation made it easy for the Chinese to tell their Indian counterparts 'Look here, McMahon was an imperialist, therefore the McMahon Line is an imperialist fabrication, therefore it is illegal'.

India should today tell China to provide proper facilities in Minsar for Indian yatris visiting Mt Kailash.

It would be a good confidence building measure.

© 2025

© 2025