'There was the indisputable fact that Savarkar knew Godse, Apte and Karkare well, he had corresponded with them closely, and funded their extremely provocative newspaper, and they looked up to him as their icon.'

A revealing excerpt from Vaibhav Purandare's Savarkar: The True Story Of The Father Of Hindutva.

Appalled by the bestiality, Gandhi began a fast unto death on 12 January 1948, at Birla House in New Delhi, where he was a guest of the industrialist G D Birla and where the rioting had spread, with refugees huddled in Purana Qila.

This fast -- the fifteenth and last in the Mahatma's life -- was to call for an end to the insanity, and built into it was the demand for the release of Rs 55 crore to newly created Pakistan.

On 14-15 August 1947 the cash reserves with the central bank of India came to Rs 220 crore, and out of it India had agreed to give Rs 55 crore to Pakistan as part of the spoils of division.

But early in October, Pathan tribesmen commanded by Pakistani forces infiltrated into Jammu and Kashmir, a state whose Hindu ruler still had not decided on acceding to India or Pakistan, and Nehru and his deputy and home minister, Sardar Patel, decided to withhold payment.

Until mid-January 1948, by which time Kashmir's Hindu maharaja had acceded to India, the money had not been released, but Gandhi's fast impelled the Cabinet to give in.

Nehru accepted it was a volte-face but felt it would work, as a 'goodwill gesture', to ease tensions with Pakistan, India having recently sought UN intervention on Kashmir, and burnish India's image abroad.

Patel was less amenable than Nehru to releasing the money, but that was the least of their differences. Other sharp divisions had arisen, and Gandhi was requested to play the role of reconciler.

The critical difference was over Hindu-Muslim relations. Nehru was incensed over violence against Muslims by the Hindus in India, and in a secret note to his Cabinet asked irately if India wanted to 'make secure and absorb as full citizens the Muslims who remain in India' or 'do we wish to make it, as certain elements appear to desire, definitely a Hindu or a non-Muslim State?'

Patel and some other close Congress colleagues such as Purushottam Das Tandon and J B Kripalani faulted Nehru for not recognising the reasons behind Hindu fears and believed that the prime minister was unfairly singling out Hindus as the aggressors when fanatical hordes were running riot on both sides.

They blamed Nehru for what they saw as his ignorance of the plight of the Hindu refugees who were the victims of much violence, and for erroneously dismissing their concerns as 'communal'.

Nehru swore by what he called the country's 'composite culture', while Patel, by no means communal, had a certain faith in the Hindu underpinnings of Indian culture.

There were other contrasts and differences too, which built up quickly once they began work as prime minister and deputy prime minister amid the mayhem unfolding all around.

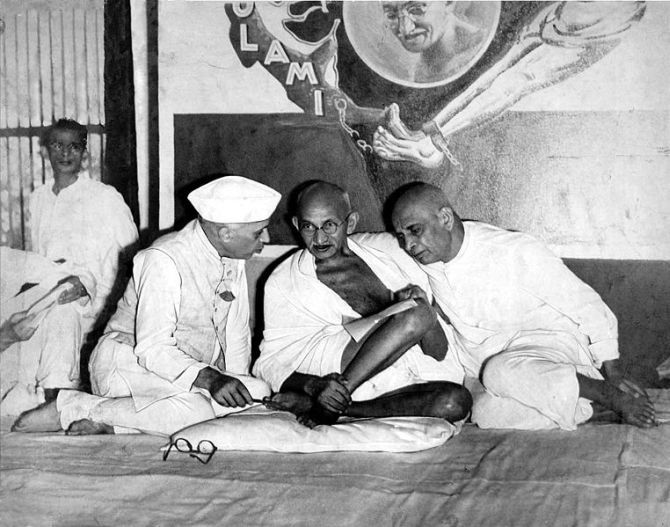

Naturally, the warring twins turned to Gandhi to try to find a way out. Gandhi did not take sides immediately, but it was decided that he would see Nehru and Patel together so that issues could be thrashed out face-to-face.

On 30 January 1948, minutes after one such meeting with Patel in Birla House to try to effect a workable peace between his two illustrious disciples, Gandhi stepped out on to the garden lawns on the premises for his evening prayer meeting.

He had hardly reached the lawns, with arms around his grand-nieces Manu and Abha, when a man in the crowd bent down to touch his feet and rose up in a flash and pumped three bullets into the Mahatma at point-blank range.

It soon emerged that the man who carried out the assassination that shocked the world was a Marathi-speaking Brahman from Pune.

His name was Nathuram Godse, he was 37 years old and he was the editor of Dainik Hindu Rashtra, on whose masthead he carried a picture of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

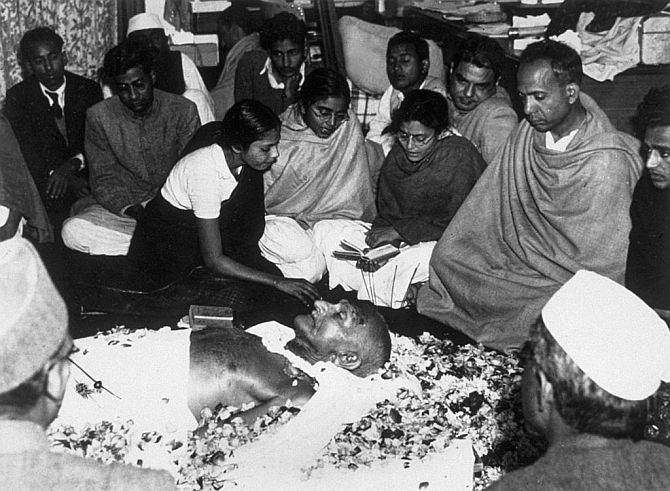

As Gandhi was cremated amid colossal public grief, more facts came to light from the assassin's interrogation by the Delhi police, who had taken him into custody from the murder scene after he had made no attempt to escape.

Godse, born in 1910, hailed from a modest middle-class household; his father Vinayak was a postmaster with a transferable job.

He had failed his matriculation exams but later studied history and sociology and had first met Savarkar when he was 19 when the Godse family travelled in 1929 to Ratnagiri where Savarkar was then interned.

This was a defining moment for Godse, who would be a lifelong follower of Savarkar and his ideology.

In the early 1930s, Godse, who started out working as a tailor, became one of the early recruits to the RSS, but once Savarkar rejoined politics in 1937, he joined the Hindu Mahasabha.

When Savarkar launched his civil resistance campaign against the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1938, Godse led the inaugural group of protesters, courted arrest and spent a year in prison.

Another man who joined the Mahasabha around the same time was Narayan Apte. A year younger than Godse, Narayan was the son of Dattatray Apte, a Sanskrit and history scholar based in Pune.

After acquiring a bachelor's degree in science, Narayan moved to Ahmednagar, about 110 kilometres from his home town, to take up a job as a teacher in a missionary school.

Here he joined the local Mahasabha unit headed by one Vishnu Karkare. Having lost his parents early in childhood and pushed into penury, Karkare, of about the same age as Godse and Apte, had studied at an orphanage in Mumbai before he moved to Ahmednagar to open a tea and puri shop.

Gradually the small shop was converted into a smallish hotel and then into a sizeable one, where needy students were often given rooms either free or at nominal rates. In 1943 Karkare was elected civic councillor on a Mahasabha ticket.

Through him Godse, who was living in Pune, got to know Apte, and when Apte moved back to Pune, having obtained a job as an assistant recruiting officer in the army, the two became good friends.

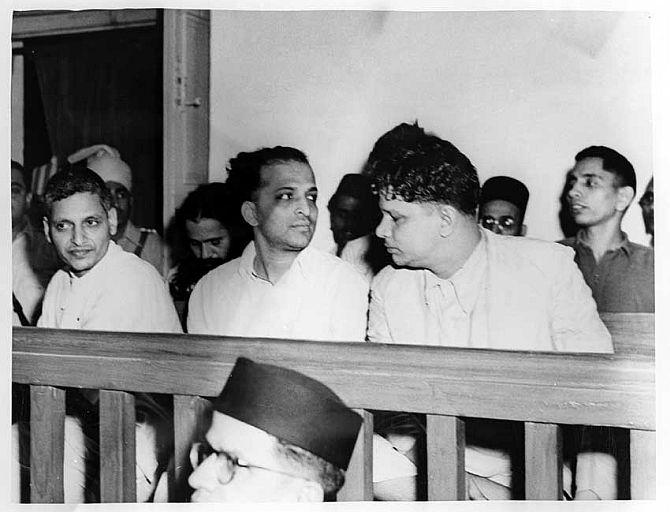

Front row, left to right: Nathuram Godse, Narayan Apte and Vishnu Ramkrishna Karkare.

Seated behind, left to right: Digambar Badge, Shankar Kistaiya, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (wearing a black cap), Gopal Godse and Dattatraya Sadashiv Parachure. Photograph: Photodivision

All the three Mahasabha men were, like their hero Savarkar, Chitpavan Brahmans, and all three were implicated in the murder plot.

Apte and Karkare had mixed in with the crowds on the lawns of Birla House when Godse pulled the trigger.

Godse had made it clear to them that he wanted to do the deed himself and they should not directly participate, because Apte had a wife and child to look after, and Karkare had the resources that would help run their paper.

Savarkar had given Godse a loan of Rs 15,000 in 1944 to start a newspaper called Agrani (Forerunner). With his friend Godse as editor, Apte had agreed to be the paper's manager.

That year the Agrani ran, with evident pride, a story on its front page with a picture of Apte, saying he had led a group of nationalist youths who had heckled Gandhi when he was visiting the hill station of Panchgani, 80 kilometres away from Pune.

As the communal temperature soared from 1945 onwards, Agrani was accused by the Raj of violating the Press Act with its inflammatory writings that incited communal hatred.

In letters written to him, both Godse and Apte implored Savarkar to write for their daily, from its first issue onwards. But Savarkar did not contribute, except for allowing them to carry all his public statements, issued from time to time.

When the government asked Godse and Apte to shell out Rs 6,000 as a security deposit in 1946 to stop them from putting out any more incendiary writings, Savarkar made a public appeal to every family that believed in Hindutva to contribute one rupee to show solidarity with a paper that was 'truly the forerunner of the ideology of Hindutva'.

That deposit was forfeited as the paper refused to mend its ways, and it was quickly thereafter renamed Dainik Hindu Rashtra.

The morning after Gandhi's assassination, anger against the Brahman community took the form of violence in many parts of the Bombay Presidency.

In the afternoon, a tall and handsome police officer raided Savarkar's Shivaji Park residence. He was Jamshed Dorab Nagarvala, the Parsi head of the Bombay police's Intelligence Branch.

Nagarvala's team searched the place and seized all of Savarkar's papers, 143 files and some 10,000 letters. Savarkar was not apprehended that day.

Five days later, another police team sent by Nagarvala knocked on Savarkar's doors, and when he went forward to meet them, told him he would have to go along with them.

'So you've come to arrest me for Gandhi's murder?' he asked. The cops nodded.

The police had no material to produce in the magistrate's court for his arrest and remand. Among the letters they had seized were almost twenty from Godse and a dozen from Apte, but none that contained anything that directly implicated him in Gandhi's murder.

But there was the indisputable fact that Savarkar knew Godse, Apte and Karkare well, he had corresponded with them closely, and funded their extremely provocative newspaper, and they looked up to him as their icon.

Indeed, the three men were not merely Hindu Sangathanists or Mahasabha members; they could truly be described as Savarkarites, so totally did they echo his word, his ideology, his philosophy and intense dislike for Gandhi.

They were also pretty convinced that Gandhi's alleged pandering to and humouring of Jinnah was responsible for India's Partition.

So Savarkar was arrested and booked under the Preventive Detention Act, a draconian colonial legislation. Thus made a 'detenu', he was taken to Arthur Road jail in central Mumbai.

Over a month later, he was arrested by the Delhi police for being part of the conspiracy -- though he was already under arrest under the Preventive Detention Act and already in Arthur Road jail, where he remained even after his arrest by the Delhi police.

In mid-May the government issued a notification naming nine persons, including Savarkar, as accused and declared that the trial in the assassination case would be held in the Red Fort in Delhi, with Special Judge Atma Ram presiding.

Excerpted from Savarkar: The True Story Of The Father Of Hindutva by Vaibhav Purandare, with the kind permission of the publishers, Juggernaut.

© 2025

© 2025