More noticeable than the hue of his shirt was his mast style in the witness box.

He seemed to be reinventing the truth every few minutes.

He yarned on and on, navigating his testimony further and further away from the facts, but he never lost his aplomb.

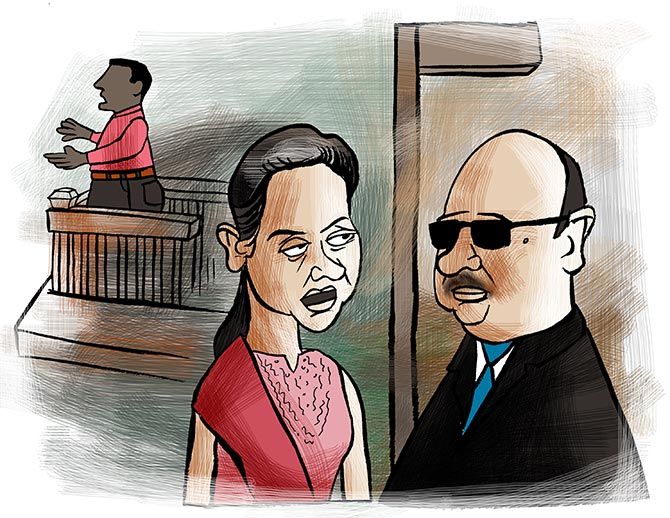

Vaihayasi Pande Daniel reports from the Sheena Bora murder trial.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

The extended Panchatantra Season continues in the Sheena Bora murder trial.

Three more panchas, witnesses to the series of panchnamas (testimonies) created during the police investigation into Sheena's 2012 death, have through late April and May, in monotonous succession, hit the witness stand at Courtroom 51, Mumbai city civil and sessions court, located at Kala Ghoda, close to the baking Oval Maidan in the southern part of the city.

The mood inside the court complex these past weeks has been quite different from what has been unfolding beyond its windows.

The excitement and colour that has enveloped most of India, and briefly Mumbai, as the country votes, seemed to stop short at the doorway of the court. Like a court, it would appear absurdly, is unaffected by elections. It is certainly a sanctuary from the bitter, vindictive election season of 2019.

The day after Mumbai voted on April 29, crossing 55 per cent, the courts were deserted with many cases adjourned.

The courtyard below, where hundreds of prisoners, and their khaki security, arrive daily from different jails, was that day empty of it usual bustling flow of people. And desolate.

No relatives with their bags of tiffins and fresh clothes and their string of little children filled the corridors.

This was because police escorts, recovering from strenuous election duty across the city, and part of the state, had not been available to bring any of the accused into court on April 30.

Elections, such a special opportunity for all of India, are, in any case, a process that jails, prisoners (serving sentences) or the accused are not at all affected by. And it probably is the same for the policemen and policewomen, who likely don't get a chance to vote, given their long shift hours on election day.

India is one of the few (or maybe only) democratic countries in the world that does not allow either any kind of felon or more importantly an undertrial to vote in its 1,400 jails, even though undertrials may rot in jail past two elections before getting their date in court or their next chance to vote, if found innocent.

According to the 2014 figures of the National Crime Records Bureau, India has 282,879 undertrials and 131,517 convicts in its prisons, a population equivalent to some of India's Lok Sabha constituencies, actually roughly equal to the number of people who went to vote in Mumbai South in the last election.

Though as per Article 326 of the Constitution, every person who is a citizen of India and who is not less than eighteen years of age shall be entitled to be registered as a voter at any such election.

But Section 62(5) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 prohibits all those who are confined in a prison or are in lawful custody of the police from voting.

This provision has been challenged before in cases that went up to the Supreme Court. India's highest court ruled the restriction imposed by the ROPA was not unconstitutional and was in public interest. A subsequent ruling in the Patna high court in 2004 on felony disenfranchisement spelled this out further and stated that 'the right to vote is a statutory right. The law gives it, and the law can take it away'.

A few days ago, the courts broke for summer holidays and the hours are shorter. That and the temperatures look to have also contributed to the sluggish vibe around there.

Proceedings in the Sheena Bora murder, reflecting this general torpidity, have been slow-footed too ever since the period of panchas began in this courtroom in mid-March. There appears to be some sort of connection to the elections for this slowdown, but no one can explain why.

Since panchas are procedural kind of witnesses, background non-characters, more part of the stage props, who have very little to say, who never knew/met either the accused or the victim, each pancha hearing lasts a bare half hour or less and only a few lawyers attend.

None of the big guns are needed.

It is hard to remember even what Indrani Mukerjea's lawyer Sudeep Ratnamberdutt Pasbola looks like anymore. Or recall the sound of that gravelly, gruff voice as he attempts to bring a witness to his knees (or tears) during a 'cross', considering one hasn't seen him in action since early March.

One is beginning to miss his stern presence and the playful little tussles between him and CBI Special Prosecutor Bharat Badami.

Lawyers for Accused No 2 Sanjeev Khanna, Indrani's ex husband, and No 4 Peter Mukerjea, Indrani's soon to be ex-husband, hardly show up since they have no plans to cross-question the smaller witnesses, which are only of relevance to Accused No 1 Indrani.

Add to that the fact that Peter, who was denied medical bail by both the lower court and on May 8 by the Mumbai high court, is still recovering from extensive bypass surgery in Arthur Road jail, central Mumbai, has not been able to make it to court. In his absence, naturally, neither his relatives nor his friends have been attending either.

The courtroom has not been half full during the last two panch dates -- a Sandip Pawar, an unemployed Santa Cruz youth testified April 24, and Ganesh Shivaji Patil, a lottery seller turned Navi Mumbai auto driver, testified May 4 in connection with the murder vehicle -- with less than 10 people in the room for each hearing.

The electricity is definitely missing (the 2 RPM fans are feeling its deprivation too).

And even Indrani with her new hair dos or cool summer style or CBI Special Prosecutor Kavita Patil's graceful saris (the last was a breathtaking black and gold cotton one) cannot make up for that.

It seemed the hearing of Friday, May 10 was destined to unfold in the exact same way when panch Sushant Shivram Sawant, Prosecution Witness 44, came to Courtroom 51 on a hot, sultry, summer day to depose.

But Friday's hearing finally brought back a few moments of astonishment and liveliness to Courtroom 51.

First off, on entering the courtroom one discovered Sawant's testimony, instead of being conducted by Patil or Badami, was being handled by a tall, balding, bespectacled man, with a burly build, heavy jowls, officious-looking but dapper in black suit and blue patterned conservative tie.

He, it turned out, was CBI Special Prosecutor Ejaz Khan, who had been transferred back to Mumbai from Delhi and would now assist in a few CBI cases like the Sheena Bora trial.

His official designation, he said later, was additional legal assistant. A senior prosecutor, who has worked earlier on cases like the Adarsh housing scam, among others, Khan, had a stern, no-nonsense appearance and a crisp, practised manner in the courtroom.

Sawant was a surprise too.

As panchas go, he was matchless.

There was very, very, very little that was believable about him at all.

Or true to life.

Once a driver but now a self-styled social worker, who went to the police station off and on help people with their police work "NOCs, license," he happened to be summoned by the Khar police, north west Mumbai, to be a panch.

But it was not entirely clear how he came or rather waltzed into the picture.

Initially, via his testimony, it appeared that like most other Khar police station vintage panchas, he was hanging about the station on some footpath outside and was approached.

Later, while being cross examined, he said -- though he knew no police personnel even though he went regularly to the police station, they knew him -- and that was why he had been called from his home at the Gangubai Kalu Kapse Chawl, Khar, north west Mumbai, to stand as a panch.

A dark, large bulky man of short stature, with a Teletubby gait, clad formally in a natty pink shirt and black pants, polished shoes, Sawant's age also varied between different testimonies – 25 in 2015 and 48 in 2019.

More noticeable than the hue of his shirt was his mast (carefree) style in the witness box. He seemed to be reinventing the truth every few minutes.

He yarned on and on, navigating his testimony further and further away from the facts, but he never lost his aplomb.

As his account cruised along, before the astonished court, often ending up in a pretty treacherous cul-de-sac or two, Sawant simply picked it up, shook it out and took it another unheard-of direction.

Sample:

When he was asked how he could have regularly visited the Khar police station to do 'social work' and not gotten to know any of the police personnel there, his answer, which CBI Special Judge Jayendra Chandrasen Jagdale translated in English, meandered on in Marathi stunningly, thusly:

"I have been involved in social work for more than 15 years. It is not correct to say that, to do social work, I have to visit the police station. I have visited the Khar police station only to do social work and not for any personal work. I cannot exactly state when I first visited the Khar police station."

"The policeman visited my house and told me to come to the Khar police station. I cannot recollect prior to that, when I had last visited the Khar police station."

"Whenever, I visited the police station, I never met police officers for social work. I never met anybody in the police station. I never disclosed my social work to the policemen in the police station."

Sawant had been called to the police station on August 30, 2015, to act as a panch, along with another panch named Hasim Shaikh, in the case of "an accused", who would be revealing certain information before the police that he had not been done so before.

The accused was Sanjeev Khanna, who had apparently confessed.

Sawant said he had no idea which case Sanjeev was connected with nor had he heard of the Sheena Bora murder case.

Sawant in Marathi: "Sanjeev Khanna disclosed that, they have killed Sheena Bora..."

Gunjan Mangla, Indrani Mukerjea's feisty lawyer interrupted immediately and sharply. She raised an objection that the alleged confessional part was not admissible in this evidence.

The judge agreed and said he would note her objection.

The Social Worker continued: "He disclosed that he would show the police the place where the body parts of Sheena Bora were burned (at Gagode Khurd, near Pen, Raigad district)."

There was an awkward pause. This looked to be a significant misstep as the prosecutors all exchanged wary glances.

Sawant ploughed on, hamming it, pretending like he hadn't said that: "He said he would show the petrol pump where they had purchased petrol (that day)."

It transpired that Sawant and Shaikh had agreed to act as spot panchas when Sanjeev took the police to the Indian Oil pump on the highway beyond Panvel where Indrani, the Mukerjeas' driver Shyamvar Pinturam Rai and Sanjeev had filled petrol in a can on April 25, 2012, on their way to Gagode Khurd to dispose of Sheena's corpse.

A half hour later, Sawant recounted, on August 30, 2015, he and Sanjeev were loaded into a jeep along with a police officer, Hasim Shaikh, and two constables and a police driver.

They took off, with Sanjeev, who knew no roads of Mumbai since he was a resident of Kolkata, miraculously navigating and getting the whole jeep load miraculously to that very petrol pump, that had he with Rai and Indrani visited three years before, among the 10 or so that dot this stretch of the highway, on his first try.

At the pump, Sawant said, the police interrogated the staff and asked for the owner who was not on location. The owner was asked to meet the police at a later date.

Half an hour later, The Great Pump Expedition was over and Sawant headed home in the jeep with the group. They did not visit Gagode Khurd in spite of Sawant's reference to that spot in his testimony.

At the end of his 'examination in chief', Sawant was asked to identify his signature on the panchnama. He was also asked if the said accused was in court. Sawant scanned the room momentarily and his eyes fastened on a disbelieving but resigned-looking Sanjeev Khanna, who later said he had never set eyes on Sawant in his life, let alone picnic with him on a Sunday morning in Panvel.

In absence of Niranjan Mundargi, Sanjeev's trial lawyer, his spunky young assistant Keral Mehta, wearing over-sized glasses, took Sawant over for his cross examination, with Mangla at her side assisting her, a testimony to young women power in court.

Pasbola, who had arrived on Friday too, after a long hiatus, with the objective of cross-examining Sawant after Mehta, supported them.

Mehta asked Sawant if she could speak to him in Hindi, but the ex-driver said he was not comfortable in Hindi and didn't know much of the language.

The lawyer, whose Marathi wasn't top drawer, nevertheless started off in that language, confidently and boldly, making some initial enquiries of Sawant.

Mehta in Marathi: "Do you remember what day of the week it was?"

The prosecutors immediately objected saying how could the witness possibly remember that.

Judge Jagdale intervened gently: "Given his memory of (the facts) she is asking..."

Sawant could not recall.

Mehta asked him about his social work.

Sawant began expansively about his desire to help "needy people."

Sotto voce, Pasbola, smiling broadly, muttered something amusingly about the calibre of social work Sawant was engaged in.

Mehta, being Mundargi's true assistant, like he would have, pulled up some geography to corner Sawant with.

She asked about the time taken to reach the petrol pump, their arrival time, how many toll nakas they crossed, where it was located on the highway and its name.

Sawant tentatively said it was called Balaji and they took 45 minutes to reach, arriving at 12, 12.30 pm, that it was on the left side of the Mumbai-Pune highway and he couldn't remember any toll naka apart from the Vashi one.

The young lawyer then smartly and deftly asked a series of questions that adroitly piloted Sawant, unbeknownst to him, into quite a sticky spot.

She first checked if Sanjeev had been wearing a mask when they left the Khar police station, as the accused customarily do.

Sawant said he had not.

She then checked Sawant's knowledge of the Sheena Bora case.

Sawant, shaking his head from side to side dramatically, in Marathi: "I was not aware about this case through the news on television before my visit to the Khar police station."

Mehta in Marathi: "When you came out of the police station were media persons were standing outside waiting?"

Sawant in Marathi: "Yes, there were."

There are no pictures recorded of Sanjeev Khanna leaving the police station that day for Panvel.

Mehta wrapped up her cross-examination, asking Sawant who had served him summons to come to the hearing Friday.

Sawant rambled off on a tale about a policeman arriving and scaring his family.

Pasbola took over from Mehta.

The judge complimented Mehta approvingly: "Nicely conducted."

Pasbola agreed warmly: ";Well prepared."

Indrani's lawyer, in total Demolition Man mode, started work on Sawant, asking him, in a sarcastic, sceptical tone, about his "samaj seva (social work)."

That was when, Sawant, after sizing up Pasbola, offered the long, nowhere answer (quoted earlier) about being the Magical Invisible Social Worker who knew no policemen.

Pasbola cannily delved about further to unearth Sawant's connections with the police, that he felt sure Sawant had.

He wondered if Sawant knew if he had been called by Dinesh Kadam, the police officer handling the murder case. And how many times Sawant had acted as panch before for the police. Or if he had ever met the policeman who summoned him either inside or outside the Khar police station.

Sawant played dumb, insisting laboriously that he knew no one nor had he seen any of the police officers that he met at the Khar police station that day, declaring slightly pompously that they knew him. Not the other way around.

Plenty of body language went with the narrative as he extravagantly closed his eyes, exaggeratedly shook his head or threw up his hands, palms face up and took sips of water, never looking at the advocate.

Pasbola resorted to a bit of Geography 2.0 too. He first determined that Sawant hailed from Mandangad tehsil in Ratnagiri district and the road to his home traversed the same route as the one Sawant took with the police and Sanjeev to that Sri Balalji pump.

Pasbola in Marathi: "Didn't you used take the same route to go to your village?"

Sawant first declared he hadn't been back to his gav since he was in school. Then he said he had not used that route to go to his village.

His moustache bouncing with laughter, Judge Jagdale pointed out to Pasbola that Sawant said he hadn't used that route to go to his village, which did not imply he had't used the route before.

In answer to all Pasbola's geography questions, Sawant played a student who must have always scored zero on his geography exam.

He denied knowing that they had been headed to Panvel when they left Khar on August 30, 2015 with the police and it was only when they reached Panvel that he realised they were in Panvel. Nor did he know, remember or believe they had crossed either Maruti Temple or the Panvel bus station.

He did know, however, that there were many petrol pumps along this route.

Interestingly he did remember that while the police were questioning the petrol pump attendants about Sanjeev's identity and if they had seen him before, they did not ask about the use of a plastic cans to fill petrol that day in 2012. Nor did he see people filling cans at the pump or know that cans can be filled with petrol.

Pasbola ended his cross examination of Sawant with a flourish, roundly telling Sawant off in his trademark gruffest voice, that this courtroom has sorely missed: "You did social work only for the police and signed on a false panchnama without going anywhere (to that location, the particular petrol pump). In the name of social work you give false testimony in court."

Sawant heard him out, not terribly bothered. Or riled. He offered a namaste to the judge and left.

Peter's lawyers put in an application for a medical bed at Peter's cost in his cell. At the previous hearing, Sanjeev's lawyers requested a special chair for the lavatory for Sanjeev since he had in issue with his leg.

Sanjeev had sandwiches with his cousin before heading back to jail. He said Peter looked much better and he had come to meet Sanjeev before coming to court.

Indrani, all in pink, sat with her lawyers for a bit. As she was exiting, she stopped in front of Badami and Khan, who were standing outside Courtroom 51.

Giving Khan her sweetest, most beguiling smile, she asked if he would now be supervising the case. She also enquired of Badami if he would still be on the case as well.

Not used Indrani's high-voltage charm, Khan agreed, looked mildly taken aback. Or maybe nonplussed.

Badami assured her he would still be around and that he and Khan would both be handling the trial.

Giving them another big smile, Indrani sailed off.

The next hearing is set for May 29.

© 2025

© 2025