'Can we even protest against this judgment?'

'We'll be called terrorists and told to go to Pakistan.'

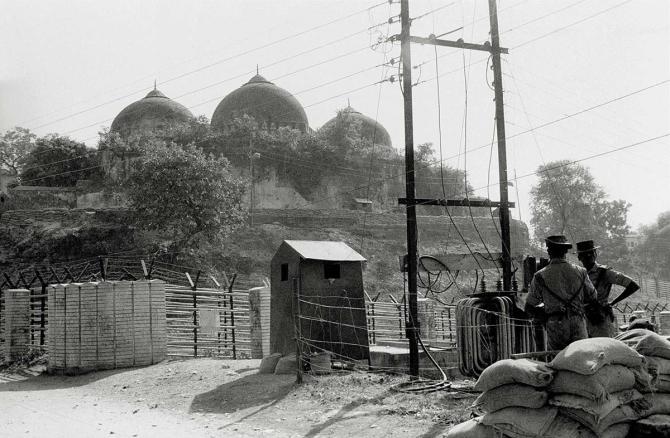

Victims of the horrific riots that engulfed Mumbai after the Babri Masjid demolition share their shock about the CBI court's September 30 verdict wioth Jyoti Punwani.

Victims of the Mumbai riots of 1992-1993 are tied willy-nilly to Ayodhya's Babri Masjid because the communal violence that affected them began hours after the Masjid was demolished on December 6, 1992. They haven't forgotten Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray's boast that his 'boys' brought down the masjid in Ayodhya.

The Justice B N Srikrishna Commission of Inquiry into the riots blamed Bharatiya Janata Party leader Lal Kishenchand Advani's rath yatra for increasing communal tension in Mumbai in the period prior to the demolition.

As one Mazgaon, south central Mumbai, victim testified before the Commission, 'Such was the atmosphere as a result of the VHP processions in October (1992), that people who would otherwise be friendly, became distant, and an atmosphere of distrust was growing.'

Jogeshwari, north west Mumbai, resident Asif Sheikh (name changed) had heard Sadhvi Rithambara urge Hindus to break the Babri Masjid at a Delhi rally. His area was badly affected during the 1992-1993 riots and Shaikh was himself implicated in a rioting case.

That trauma, coupled with keeping track of court dates for 22 years before being finally acquitted, never left Sheikh: He still wakes up at night hallucinating that mobs are chasing him.

So when CBI Special Judge Surendra Kumar Yadav said on September 30, 2020 that some nameless 'anti-socials' had brought down the masjid, it became for Sheikh and other Mumbai victims a turning point: Loss of faith in the judiciary.

Ironically, this faith had been revived by the Srikrishna Commission.

After having been targeted by mobs and the police during the riots and then disbelieved by the authorities whom they turned to for help, these victims had given up on ever getting justice, till they found a sitting judge not only giving them a patient hearing but also vindicating what they narrated in his own report.

"People would laugh at me for going on fighting in one court or another," said bank employee Farooq Mapkar hours after Wednesday's judgment. "But I would tell them I knew I'd get justice one day, I have faith in our courts. Today I can no longer say that."

Mapkar, then only 27, was bending down for namaaz in Wadala's Hari Masjid in north central Mumbai on January 10, 1993 when he was shot in the shoulder from the back.

The firing, ordered by then police sub-inspector Nikhil Kapse, killed six namaazis, four of them inside the masjid.

The Srikrishna Commission recommended 'strict action' against Kapse for his 'unjustified firing (and) brutal and inhuman behaviour'.

Mapkar had testified before the Commission and his struggle to get Kapse punished began the day this reporter handed him a copy of the Srikrishna Commission Report soon after it was tabled in August 1998. He was then 32 years old, and an accused in a case of rioting and attempt to murder -- charges levelled by the police on all those present inside the Masjid when the firing took place.

All of them were acquitted after 13 years by the sessions court.

IMAGE: Farooq Mapkar.

IMAGE: Farooq Mapkar.Meanwhile, the Special Task Force, appointed by the Maharashtra government to act on the Justice Srikrishna Commission report, exonerated Kapse wthout giving his victims a hearing. Mapkar then filed his own complaint against Kapse, immediately inviting a fresh charge against him by the police.

Acquitted of that too, Mapkar's day in court came in 2008 when the Bombay high court, acting on his petition, ordered the CBI to investigate the Hari Masjid firing, describing it as a case which 'affects the very soul of India'.

Immediately, the then Congress-Nationalist Congress Party government in Maharashtra rushed to the Supreme Court in appeal. Describing the case as an 'extraordinary case', the apex court dismissed the appeal.

In 2010, the Central Bureau of Investigation exonerated Kapse and closed the case, dismissing the consistent testimony by other Hari Masjid victims against Kapse as unreliable only because they had been framed by him in a rioting case.

That's when Mapkar lost faith in the CBI.

Wednesday's judgment only confirmed his worst suspicion: "Not just in my case, the CBI did nothing in the 2006 Malegaon bomb blasts case too, where Muslims were falsely accused. And now this Babri Masjid case. It seems the CBI is determined not to get justice for Muslims," said the 54 year old.

For a decade now, Mapkar has been trying to challenge the CBI's closure in different magistrates' courts. Now he wonders if he should keep trying. "I doubt I'll get justice," he said for the first time in his 27-year-old fight.

This isn't about one victim losing faith in courts. Mapkar is the only riot victim who is still fighting, making him the face of the Mumbai victims.

When he gives up, it means the fight for justice for Mumbai's victims is over; the police and the State have triumphed.

***

IMAGE: Abdullah Qasim.

IMAGE: Abdullah Qasim.Unlike Mapkar, 40-year-old Abdullah Qasim lost faith after his very first attempt to get justice.

Qasim was only 12 when his father, a madarsa teacher, became one of the eight innocents to die at the hands of then additional police commissioner Ram Dev Tyagi's 'commandos' during their raid of the Suleman Usman Bakery and adjacent madarsa.

In 2001, when the STF charged Tyagi and 17 other policemen with murder for this raid, Qasim, then a final year student at the same madarsa, opposed the policemen's anticipatory bail applications as an intervenor.

He lost because, as the special public prosecutor told the court, the government didn't want custody of these murder accused; it was concerned that their careers would be affected. That blow was bad enough, but it reflected on the government, not the court.

Qasim's disillusionment with the judiciary came two years later, when Tyagi and nine other co-accused were discharged without a trial by the sessions court.

When the trial of the remaining policemen began in 2019, Qasim refused to intervene. "Nothing will come out of it," he told this reporter dispiritedly, "except that old wounds will re-open."

His scepticism got strengthened after he was summoned as a witness in the trial four times, and sent back every time without his testimony being recorded.

The CBI court's September 30 judgment has put a seal on his disillusionment.

"I had lost faith in the courts last November itself, when despite the Muslim side having stronger evidence, the Supreme Court gave the disputed land to those who'd demolished the mosque. The world was watching then. Compared to that, this acquittal is trivial."

Qasim showed this reporter videos from a television news channel where two of the accused in the demolition case boasted as they came out of court, that they had gone to Ayodhya to demolish the Babri Masjid and had succeeded in doing so.

"This is justice for Muslims," he commented dryly.

Some Muslims felt that the accused were too old to be punished, said Qasim.

"Ask those who had to grow up without their father or brother, those who lost their son in the riots, whether they'll agree with this," he said angrily.

Zaid and Hina (names changed) Qureshi lost both their father and their elder brother in January 1993 to a mob whom their mother identified as Shiv Sainiks in front of the Srikrishna Commission.

The bodies of the two were never found.

The siblings grew up seeing their mother struggle to educate them, often fainting in the heat as she went from house to house to teach the Quran, the only means of earning she was qualified for.

Today, their lives are geared to supporting their mother, now a heart patient. Hina, who has a low-paid job, can't contemplate marriage. Zaid has gone from one job to another: In his desperation to start earning, he didn't wait to finish his graduation. The lockdown has left him jobless.

Brother and sister hate talking about the past because it disturbs their mother, but the CBI judgment made them break their silence. "So nobody demolished the Babri Masjid?" asked Zaid bitterly. "Can we even protest against this judgment? We'll be called terrorists and told to go to Pakistan."

"Now what will stop the BJP from demolishing the masjids in Kashi and Mathura?" wondered Hina. "That's what they'll focus on, instead of curbing the corona pandemic and providing jobs."

Amid this cynicism, however, were voices of hope.

IMAGE: Shaheen Kadri.

IMAGE: Shaheen Kadri.Shaheen Kadri, whose home was destroyed and looted in the riots, had expected this acquittal after the Supreme Court's decision on Ayodhya last year. However, while she had no faith in the judiciary any more, this retired government officer had not lost her faith in two things.

One was divine retribution. "Look at how Vajpayee spent his last years. Advani and Murli Manohar Joshi are in the political wilderness today."

The other factor that kept her spirits up were the bonds between communities which she could witness in her own building . "My Hindu friends feel as helpless as we Muslims do. Do you think the woman with whom I shared my dabba for years wanted the Babri Masjid demolished?"

Shivaji Khairnar certainly didn't. He was a child when the 1992-1993 riots engulfed his Jogeshwari neighbourhood; Muslims he'd played with were suddenly referred to as dushman".

Last year, anticipating trouble before the Supreme Court verdict on Ayodhya, he got together with Muslims and other Hindus to form Baatein Aman Ki, a group that would dispel rumours and ward off communal trouble.

"Fortunately, we didn't need to; there was no tension at all," he said, adding however, that the Supreme Court judgment had left him unhappy.

"They should have told both parties to build a hospital on that land; not given the judgment they gave."

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025