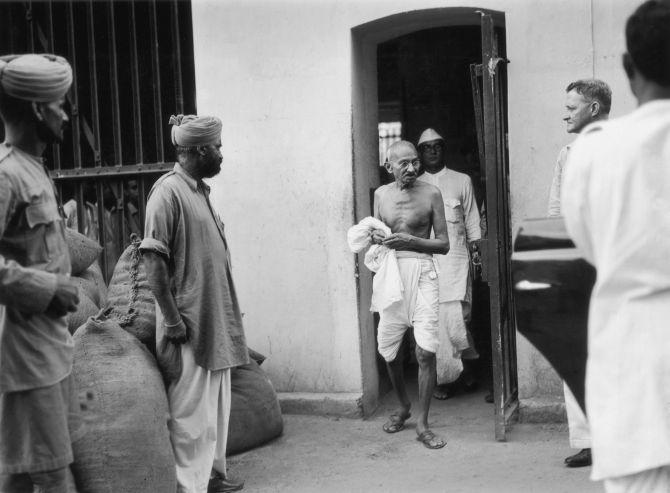

On January 30, 2019, 71 years after he was murdered, Hindu Mahasabha workers tastelessly re-enacted the crime in Aligarh.

Television channels, which conducted prime time debates when a portrait of Jinnah was discovered on the AMU canvas, were predictably silent about this distasteful assault on the Mahatma's memory.

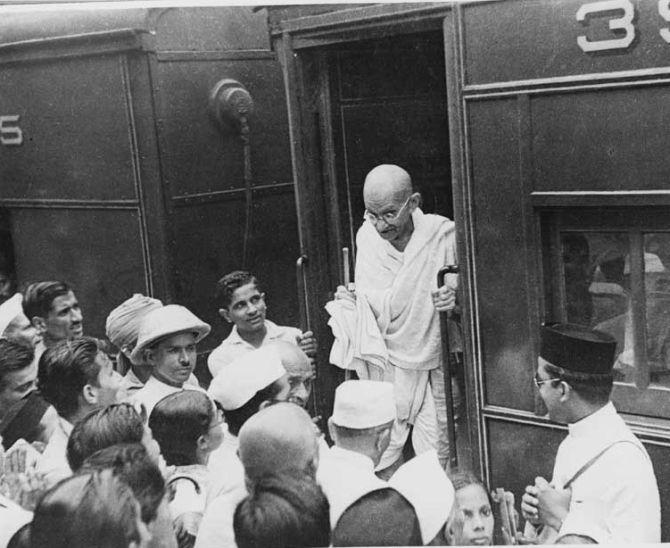

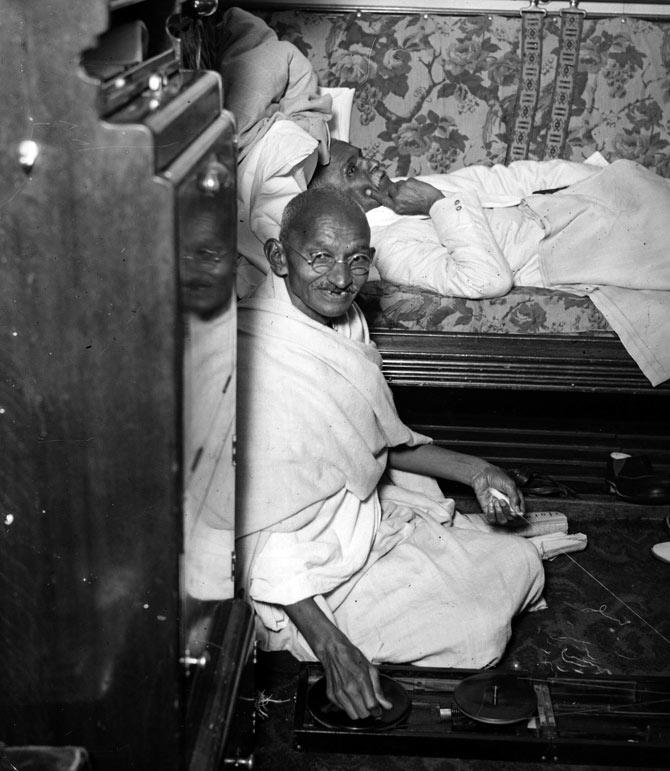

'Gandhi turned his life into a counter-intuitive experiment in old ideas like non-violence and swadeshi.'

'He offered numerous universal ideas that talk to the human condition.'

'His ability to take risks was outstanding,' says Sopan Joshi, explaining why the Mahatma's ideas are as relevant as ever.

It was a common sight late in the evening: Parents looking for their children from door to door, not knowing where they had eaten, played or slept all day.

For us children, all the homes were ours. We could enter and exit almost any house, expecting to be loved and indulged, and sometimes scolded. No, this was not a tightly knit, caste-based community in a rural idyll.

The residents came from across the country -- food, language, customs and clothing changed from house to house. Often, foreigners came and stayed, sometimes making furniture for our spare households, or playing cricket with us. Hardly anybody knew English, and it didn't matter.

Each family battled poverty with its own interpretation of frugality. Groceries were obtained on credit, school fees never paid on time. It didn't seem to matter much, though. There was music, drama, sports, art, books -- all for free.

We had no money to buy comics, so an old bachelor called Menonji bought comics with his small income and lent them to us; returning dates were sacrosanct.

Delhi was a sanctuary, a secure and entertaining place. We lived in a house inside the compound of the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi (GSN, or the Gandhi Memorial Trust), New Delhi.

We didn't know then that the trust (both literal and figurative) was created on 13-14 February, 1948. Following Mahatma Gandhi's murder, his closest friends and associates met after the stipulated 13-day mourning period.

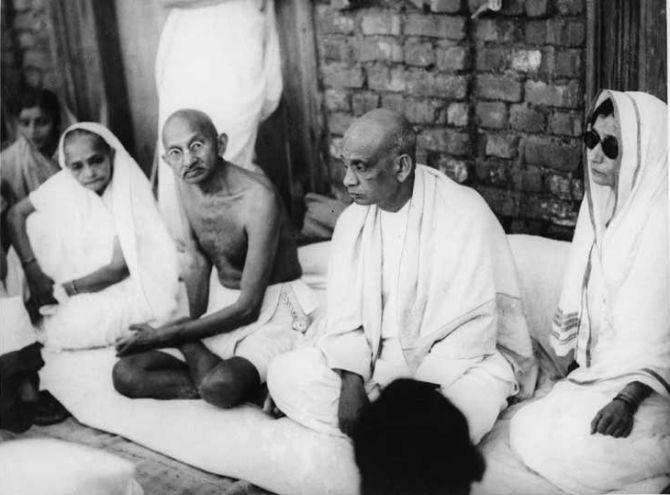

They created the trust to carry forward his memory and legacy. The list of founding signatories is a who's who of the freedom struggle, people who occupied top government positions of the day: Rajendra Prasad, S Radhakrishnan, Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, Abdul Kalam Azad, C Rajagopalachari...

The trust, however, had nothing to do with the government; it did not receive government funds. Perhaps the biggest such trust of the time made in one person's name, it was created through personal donations.

Gandhi's associates were well aware that while he took part in politics, he was, essentially, a social activist. About six months earlier, while they celebrated India's freedom, Gandhi had been busy dousing the flames of communal violence in Bengal.

Rajendra Prasad issued requests for fund collection. A separate post office was created to manage donations, along with separate wings in banks. There were large donations from industrialists and wealthy people. But most came from ordinary people, in small denominations.

The accountant had a story: An old woman came to offer small change, totalling about a rupee. When she was asked to give an address for the receipt, she said she didn't have one.

She lived on the footpath around Delhi's India Gate, where she sold peanuts. She was donating a day's earnings, deciding to fast for a day in Gandhi's memory. There were several such stories.

I tried to find out from old-timers if they had been recorded. I was told they were too numerous to record.

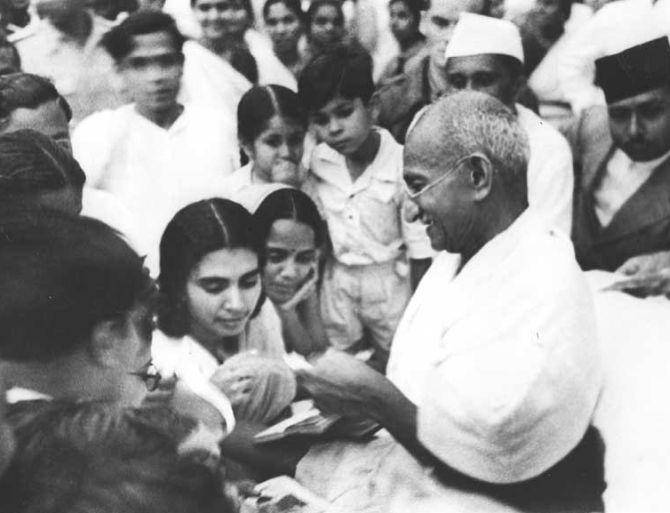

We saw more of our neighbours than our parents and blood relations. There were plenty of old-timers who had worked with Gandhi and lived in his ashrams.

Their personal stories emerged only when we asked for them. They were anecdotes of little things he did: How he dealt with people, how they were transformed by his presence, his humour, his overwhelming love.

The old-timers handled us with a similar love, with patience and tolerance. If we made a mistake or hurt somebody, the reproach always began with a loving hand placed on our heads.

Ordinariness was paramount, even among the extraordinary. Gandhi brought about an ethical shift among the well-heeled, inspiring them to serve ordinary people. It is a story of service, not entitlement.

My parents arrived in Delhi in 1968 from Indore. My father had left professional journalism to work with the editorial team of the Gandhi Centenary Committee.

The Gandhi Centenary (in 1969) was a major event at the time, with programmes and camps across the country and the world. The chairperson of this committee was the President of India, and its executive arm was headed by the prime minister.

But all the work was left to organisations like the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi and the Sarva Seva Sangh (in Wardha, Maharashtra). The government's role was participatory, not controlling.

Under the centenary programmes, capable people had been gathered from across the country to work for social programmes. These were the people we lived with.

In the 1970s, as the centenary programmes began to end, the country was entering a period of political turmoil. The movement against the Emergency was led from the same Gandhian institutions, especially the Gandhi Peace Foundation, created by the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi in the early 1960s.

Our family moved out of the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi when I was little; my father took a job with a daily newspaper. But the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi campus continued to be the centre of our social life. If we went anywhere in Delhi, we went to the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi before going home.

I struggled to adjust to life outside this secure world. None of us went to expensive schools. I adapted to survive, but I was a reluctant student. It was an extraordinary old-timer who gifted me a copy of Divaswapna (Daydream), a 1920s book by the Gujarati educationist Gijubhai Badheka. In simple, child-friendly language, it details the surreal banality of our education system.

I read it at the age of 10 and became certain that formal education was not for me. Since I could not opt out of school -- I lacked the courage -- I was going to hack my way through. This is how I got through school, college and university. I found short-cuts. I have the degrees. It doesn't matter.

Education happened outside of school and college. I picked up names of writers and poets in conversations with my favourite old-timers, and read them in my free time.

Maths and the sciences were too complex, the teachers were uninterested, and I could not summon the courage to ask my parents to spend money on tuitions (knowing that school fees were a monthly challenge).

I gravitated towards the humanities and literature. And ecology, because the National Museum of Natural History (now burnt down) was a refuge. It screened films on wildlife, it had DIY kits on ecology, it was everything school was not.

I cannot say how environmental themes became important. But I know who made them interesting and engaging. The celebrated Hindi poet Bhawani Prasad Mishra, who had spent three years in jail during the Quit India Movement, lived in the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi; he was our de facto grandfather in Delhi.

His son Anupam Mishra was a journalist and photographer known for his writing on the environment. He was the first journalist to write about the Chipko movement in 1972, when the villagers'ds struggle to save their forest from government contractors had not acquired that name.

In the mid-1970s, he wrote about the Mitti Bachao Andolan in the Narmada valley, which segued into a larger anti-dam movement later. He was like a directory of popular environmental movements; also their telephone exchange, connecting people with each other. Traditions of rainwater harvesting, efforts to conserve pastures...

His office in the Gandhi Peace Foundation was a gateway to constructive programmes and protest movements across India and the world.

It was perhaps only natural that environmental movements found an echo in institutions created in Gandhi's memory. For he had warned about the consequences of unfettered industrial development much before the dawn of a new environmental consciousness.

He made it clear repeatedly that humans were merely a part of the natural world, not its masters.

In our age, as we witness the unfolding of the Sixth Mass Extinction and debate whether to rename our age the 'Anthropocene', Gandhi's warnings seem prophetic.

It has become fashionable to dismiss Gandhi's warnings about mechanisation and technological fixation, but a lot of such criticism is based on selective reading. Gandhi was ahead of his time in understanding several aspects of technology.

Isabel Hofmeyr, a South African academic, produced a lucid book in 2013, titled Gandhi's Printing Press: Experiments in Slow Reading. It describes Gandhi figuring out the link between speed of information and imperialism.

He had begun to ask his readers (and future satyagrahis) to slow down the reading and sharing of information to a human speed, to a humane speed.

If your teenage child is struggling with #FOMO and getting swayed by online trends, you might find useful Gandhi's understanding of the speed of information and how it affects us.

Likewise for intellectual property rights. Gandhi did not assert copyright, believing copyright laws were imperial in nature; his readers were free to share his writing.

But in the early 1940s, he changed his mind. An American law professor has analysed Gandhi's use of IPR in a detailed academic paper. He says even this was a way to subvert copyright, because -- being a lawyer -- his position was informed by a 'practical idealism'.

'He also came to deploy copyright law to curtail market-based exploitation when he could. In many ways then, Gandhi's approach did with copyright law what open source licensing and the Creative Commons Project would begin doing with copyright in the twenty-first century.' Leaders of the Free and Open Source Software movement have cited Gandhi as an influence.

Gandhi was very keen on Indian languages. He firmly believed that primary education should be in a child's mother tongue. And yes, he championed the cause of Hindi becoming a national language. But his Hindi was not the pure Hindi of the "Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan" variety.

Gandhi learned Hindi very late, perhaps in his late 40s. Besides, his Hindi was syncretic, a hybrid born of Indian languages trying to talk to each other. Gandhi's Hindi embraced Tamil and Odiya and Maithili and Braji as a child embraces its grandparents.

It never would have tried to impose itself on others. It would have been the "Hindvi" of Amir Khusrau and Mir-Taqi-Mir. Gandhi knew several Indian languages to varying degrees of competence: Gujarati, Marathi, Tamil, Urdu, Hindi and Sanskrit, apart from English and some French and Latin.

During the freedom struggle, it was common for jailed protesters to learn each other's languages. Their love of India was built on a love for its cultural variety. The poet Bhawani Prasad Mishra learned Bengali and Persian during his incarceration, which I learned from his daughter when I was trying to learn Persian.

In fact, it was my interest in the environment, FOSS and Indian languages that made me read Gandhi. That's when I realised I had actually not read him before, because we tend to take him for granted. I was surprised by the nonsense that circulates freely in his name.

So many quotable quotes are attributed to him in words he never said nor wrote. By people desperate for somebody else's grand quote to elevate their mediocrity.

And the institutions bearing his name, once so full of life and love, are bereft today. Mired in disputes over control of positions and property, out of sync with their mandate, living in a time warp.

In stark contrast to the excitement and social outreach of the 1969 Gandhi centenary, the 150th year of Gandhi's birth in 2019 is littered with irrelevant programmes on Gandhi's 'relevance'.

A person's relevance ends with his life; Gandhi is no exception. One person's ideas, however, become relevant the moment somebody else finds a new context for them.

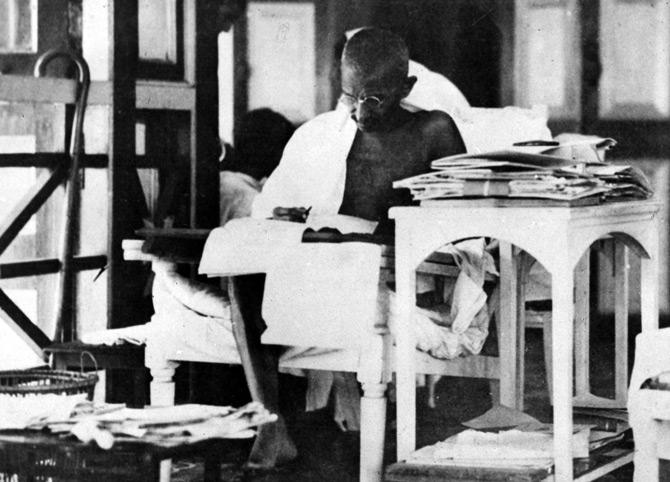

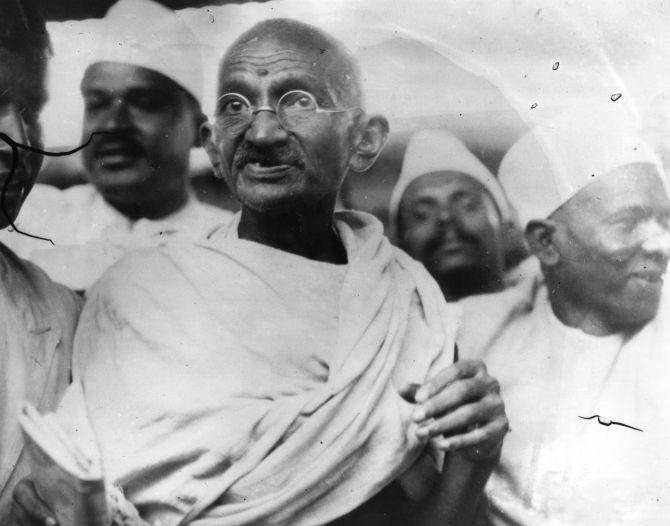

Gandhi turned his life into a counter-intuitive experiment in old ideas like non-violence and swadeshi. He offered numerous universal ideas that talk to the human condition.

His ability to take risks was outstanding. He was always willing to understand something afresh, to put hard labour into his investigation; he was never in a hurry to define and analyse.

For anybody willing to experiment at any point of time, his ideas offer a fresh, counter-intuitive edge. Gandhi is a useful sparring partner.

Sopan Joshi is a journalist and the author of two Hindi books for children on Gandhi, Ek Tha Mohan and Bapu Ki Pati, both published in 2018.

© 2025

© 2025