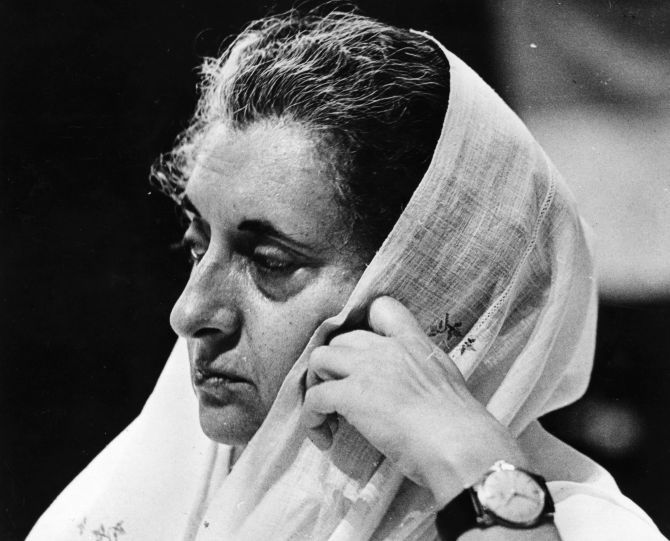

Pupul Jayakar, her friend of long standing, remembers her encounters with the woman people loved and disliked in equal measure in that fortnight before her tragic death.

I went to see Indira Gandhi on 13 and 15 October, I arrived with a tape recorder; now she was not speaking to me alone, but to history. I was to be her ambassador, representing her to an unknown future. She spoke at length of her childhood and her growing up.

Towards the end of that morning I asked her what she considered the basic problem of this country.

Her response was immediate. 'The basic problem is poverty. If that is solved, nothing else matters.'

Again she stressed that in the process of improving the level of living, that special quality which gave the Indian people an inner strength should not be lost.

I commented that with development, in most countries, there was an end to serenity.

Did she think it would happen to India?

'I don't really know, but we have to try and preserve it. However carefully we try to separate what is really worthwhile and eternal in our values from the many superstitions which have gathered around them, we cannot always succeed.'

'Most people see religion not as a basic philosophy or the essence of life but as the mantras that they may have learnt to utter at a given time. That is why my father spoke up so strongly about the scientific temper and against astrology.'

'People must go back to the very roots, to the source of faith. Our philosophy says that the divine is in each one; there is light and strength in each one of us. We have to find a way of discovering the energy that is within us.'

Later, when we were alone, we spoke of her marriage to Feroze Gandhi.

I asked her 'When you were 16 or 17 years old, didn't you feel the desire to be admired?' 'Pupul, I was so sure that I had nothing in me to be admired.'

She then recalled that the first time she had been openly admired was at Shantiniketan, and how she responded in anger, feeling that she was being made fun of.

'Even with Feroze, it was not at all sex. I tried to explain to him that I wanted children and companionship.'

In the sixties, when Indira was living in her father's house, or even later, stories had circulated in the gossip circles of Delhi, that she had relationships with other men.

I myself had heard these stories, some spread by her close relatives. I knew Indira well, saw her frequently and felt that these rumours had no basis in fact.

She delighted in being admired, liked to be surrounded by good looking, witty, intelligent men, but the sexual side of her was underdeveloped. She appeared to confirm this that autumn afternoon.

'A part of the problem is,' she said, 'that I do not behave like a woman. The lack of sex in me partly accounts for this. When I think of how other women behave, I realise that it is a lack of sex and with it a lack of woman's wiles, on which most men base their views of me.'

She did not think she could have married anybody except Feroze, 'even though they fought like wildcats' and he had asked her for a divorce.

She recalled the occasion -- how she had been very upset at the time, had resisted and wept so that her face was swollen.

'Finally I said to Feroze that if "it (a divorce) is what you want, all right".'

'He turned and said, "Do you mean to say that you will let me go like that?"'

'Then I lost my temper and said, "This is the limit. I say -- we have our differences, but there are the children; all you say is separation. When I say -- all right, you blame me".'

'Feroze was very attached to me, but he listened to what other people said. You know Pupul, I have never carried on with anybody. But they would spread all kinds of stories and Feroze would believe them. I said to him, "How can I ever prove anything? I hardly go out except with my father and you, and when I am touring I always have someone with me".'

I asked her whether Feroze was upset when she came to live with her father. 'It was Feroze's idea. My father asked me to set up his house. I discussed it with Feroze and he said go. But by then he already had an eye on somebody.'

After 1950 Feroze was a member of Parliament and lived in Delhi. The situation seemed to have become more complicated.

Feroze had made her feel very possessive. 'He said to me, "Don't strangle me with your love." It was very difficult,' she said, 'to strike a balance in our relationship.'

On the evening of October 26, I was at the prime minister's house with some urgent papers relating to the future of handloom weavers.

She made some notes on her memo pad which was always with her, put it aside and turned to me. I could see that she had laid aside all her problems.

There was an openness, a mellowness in her as she watched from her study the leaves on the bushes respond to changing light of the setting sun.

Suddenly she turned to me to say that she had decided to fly to Srinagar the next morning. Governor Jagmohan was reluctant and unhappy over her visit.

He spoke of unrest in Srinagar and of unruly crowds wandering through the city. He was perplexed by her persistence, but she was determined to undertake the trip to see Srinagar in autumn when the chinar leaves explode in colour: From a deep vermillion through tones of burnt sienna to pale amber.

'Have you visited the valley in November?' she asked me. I said yes and suggested that she visit Gandharbal to see the great grove of chinar trees turn autumnal red.

She said she wanted to sit under the trees, to drink in the colours, to watch the chinar leaf reach its maturity and drop from its stem. Her two grandchildren, Rahul and Priyanka, were to accompany her.

She was to lunch with me a week later, on November 3, to meet J Krishnamurti and the Dalai Lama. I asked her whether she remembered the engagement. 'It will be a historic occasion and I look forward to it,' she replied.

'You remember, Pupul,' she asked me, 'that ancient chinar tree in Bij Bihara? I have just heard that it had died.' She spoke as if she was referring to an old friend.

'Once again', she said, 'a feeling is arising in me, Why am I here? And now I feel I have been here long enough.'

I had rarely seen her in such a mood, her thoughts entangled with death.

'Papu used to love rivers, but I am a daughter of the mountains and my heart is free of care. I have told my sons,' -- for an instant she appeared to forget that Sanjay was dead -- 'that when I die, to scatter my ashes over the Himalayas.'

It was a strange remark, strangely made.

'Why do you speak of death?' I asked. 'Isn't it inevitable?' she replied.

Excerpted from Indira Gandhi, by Pupul Jayakar, Viking, Rs 295, with the publisher's permission.

This feature was first published on Rediff.com on November 19, 1997.