'Our biggest problem has been keeping this country together.'

'Nation building is never easy. It is a very difficult task.'

'Even 70 years is not too long a time.'

An old time civility distinguishes Lieutenant General Anand Sarup, Mahavir Chakra.

Decorated with the nation's second highest gallantry award for bravery in the 1971 War, the war hero is remarkably humble about his many military achievements.

Just as India became free, he joined the Indian Army and has journeyed with the country from her days of captivity to its freedom to its 70th year as a nation.

On a quiet summer evening, the 88-year-old general, graciously shared his memories of August 15, 1947 with Rediff.com's Archana Masih.

The captivating conversation revealed how we understand our past better when we hear it from those who have lived, seen, heard and felt it.

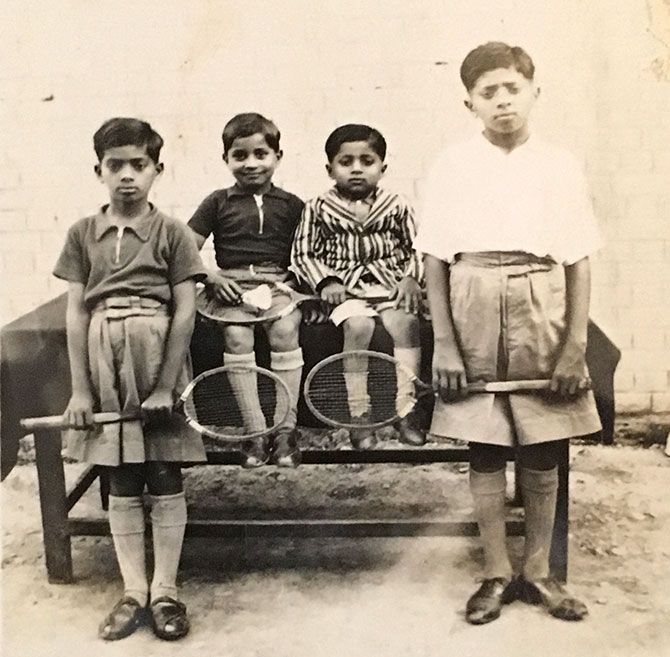

Photograph, Kind courtesy, General Anand Sarup.

'My birthplace on the Indus'

I was born in Dera Ismail Khan in the frontal tribal area (bordering Afghanistan) in 1929 and spent the first eight years there.

My father was in the army. He was posted in Kohat and Thall which were among the forts built by the British to provide cover to British troops in order to maintain law and order.

Although families were not permitted, my father had requested the commanding officer to let me come for 15 days.

As a boy I did go and stay in both Kohat and Thall.

These forts were not grand like the Rajasthan forts or Lal Quila -- these were fortifications built by the British.

The British fought three Afghan wars.

In the First Afghan War, only one man came back.

The rest were killed by the Pathans (It was Britain's worst military defeat in the 19th century).

'I have never been back to Dera Ismail Khan'

My father used to tell me that once he was on a patrol along with an officer on a horse and two other ranks.

A Pathan was following them. After a little while, the officer asked why he was chasing them and he replied, 'I have one bullet; I am waiting for the opportunity that you three get in line and I get you all in one bullet. Otherwise I'll get killed by you.'

The Pathan was a very good shot.

Since it was very hilly terrain, they (the Pathans) used to sit on top of the hill and people travelling on the roads were very vulnerable.

The British sent the Second Expeditionary Force into Afghanistan, which was also defeated, and so was the Third Expeditionary Force.

Finally, the British decided never to send troops to fight a war in Afghanistan, but undertake punitive expeditions.

Like when the tribals looted Dera Ismail Khan and went back -- the British used to make punitive expeditions, destroy whatever infrastructure they had, but never stayed back or went with the intention of occupying the land.

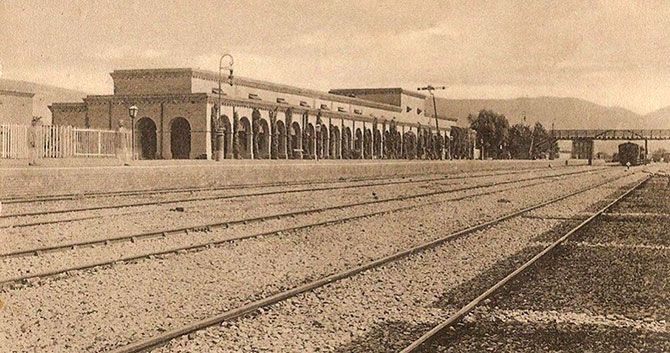

Dera Ismail Khan was on the banks of the Indus.

During the summer, the river became very wide and steamers would take you to the other bank.

During winter, the river split into 10 to 12 small channels, boat bridges were built over them and we travelled on tongas over the river.

I have never been back to Dera Ismail Khan. I had hoped I would some day, but it didn't happen.

'The first time I saw the Indian flag go up was in school'

In 1937 my father got posted to Ambala. He was with the mountain artillery which had guns that could be broken into 3 to 4 parts and loaded onto mules as opposed to field artillery which is carried on vehicles.

He was a junior commissioned officer, an educated man who got his emergency commission in 1942 and retired as a captain.

I was in Class 4 when I came to Ambala and shifted to the King George's Royal Indian Military School in Jalandhar after Class 8.

By 1942, the British had realised they couldn't stay any longer.

World War II had emptied their treasury. There were other factors like the mutiny in the Royal Indian Navy in 1946.

In the same year, the election took place and when the interim government was formed with Jawaharlal Nehru, it was obvious we were going to get our independence.

Until then the state governments had their chief ministers, but the Centre didn't.

The first time I saw the Indian flag go up was in school in Jalandhar. I saw the Union Jack lowered. I have a photograph from that day.

Photograph: Photo Division, Government of India.

'Independence was not bloody against the occupier, it was bloody against ourselves'

The emotion for freedom was building, but it was dampened by the trauma of Partition, the migration of kith and kin, loved ones getting killed on either side.

The death, carnage and massacres that took place at that time diminished the spirit.

Those who came from the other side went to their relatives. We had four families besides our own in a three bedroom house in Ambala cantonment.

My father had retired after 30 years of service and had to vacate his army bungalow.

We hired a bungalow a little distance away and relatives started coming in July, August, September.

Soon after, the deputy commissioner sent a notice that our rented bungalow was required, therefore we had to vacate it.

They said they would allot land in a village in lieu of the property so there were a lot of anxieties.

I remember receiving my sister in Jalandhar. Massacres were taking place in the trains.

Trains were coming with rotting bodies. The news, also rumours resulted in anger and retaliation.

You didn't know if your dear ones were going to arrive safe on this side or not.

Consequently, all trains were stopped in Indian Punjab.

Independence Day was dimmed for many of us with such anxieties.

Those were hard times for some people, we were lucky that we were on this side, but many suffered badly.

Independence was not bloody against the occupier, it was bloody against ourselves.

'This great human tragedy unfolded before my eyes...'

My school was located on the Grand Trunk Road and everyday and night we used to see caravans, carrying the old, rich and poor who were displaced from their homes. They travelled in bullock carts or trudged on foot.

For me, the greater imprint of August 1947 is of these caravans and seeing this great human tragedy unfold before my eyes.

I had applied to the Indian Military Academy and had to appear before a selection board in Meerut.

The trains were not running and I was worried about what the future held for me and anxieties about the family.

The school arranged for him and another friend to travel to Meerut to appear before the board. They made their way in vehicles carrying a British colonel and his luggage for transfer to England.

From Delhi the boys travelled to Meerut and since they reached three days before time, they spent the first night in the waiting room.

The next two days were spent in the first class compartment of a waiting train. They had managed to pry open that compartment.

After the last test at the selection board, there were still no trains or buses. An officer arranged transport in an army vehicle up to Roorkee. From there they hitched a ride in a third class bogie carrying labourers to repair a railway bridge 10 km short of their school in Jalandhar.

On the last lap of the journey, they had to wade through waist deep water with dead bodies -- some bloated, others putrid -- flowing down the river. (Paraphrased from General Sarup's account in a magazine commemorating his course at the IMA).

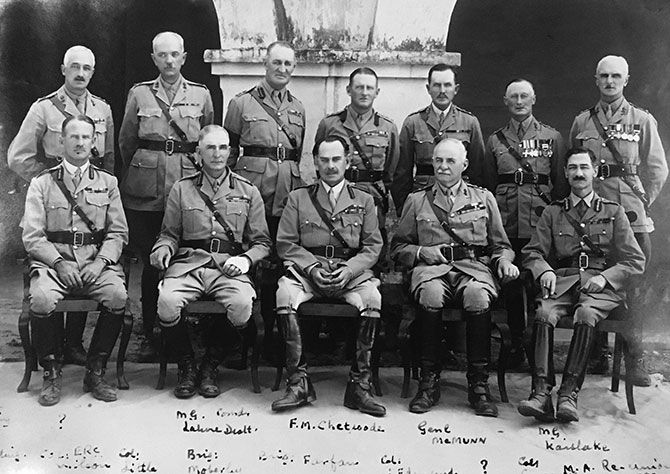

The IMA motto is taken from Field Marshal Chetwode's address delivered at the formal inauguration of the Academy in 1932 -- 'The safety, honour and welfare of your country come first, always and every time. The honour, welfare and comfort of the men you command come next. Your own ease, comfort and safety come last, always and every time.'

Photograph: Kind courtesy, General Anand Sarup.

'The British did greater damage to us by damaging our psyche'

The British acted on our psyche, anything Indian was useless, so much so that even today people think anyone who has a gori chamdi (fair skin) must be a very learned man.

The British did greater damage to us by damaging our psyche than our physical self.

The effects of Independence and Partition can be felt even 70 years later.

One doesn't know what would have happened if there was no Partition.

Who knows there may have been a civil war and Partition was a better alternative than civil war.

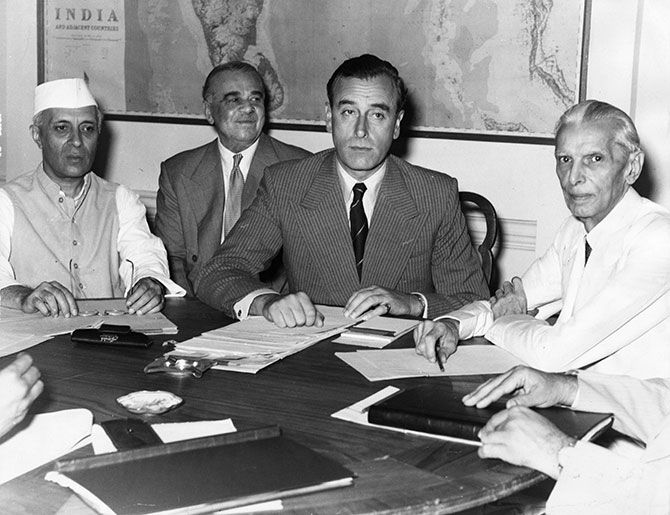

Left to right: Jawaharlal Nehru, Lord Ismay, the adviser to Mountbatten, Lord Mountbatten and Mohammad Ali Jinnah. Photograph: Keystone/Getty Images

'What kept this country together was the charismatic personalities of leaders like Nehru, Gandhi, Patel, Azad'

Sometimes the personalities of individuals can change the destiny of nations, like the clash of personalities between Jinnah and Nehru.

I saw Sardar Patel, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Pandit Nehru...

In 1951, we gave a guard of honour to the prime minister of Nepal at New Delhi railway station and I have a picture with Pandit Nehru.

What kept this country together was the charismatic personalities of leaders like Nehru, Gandhi, Patel, Azad.

People were prepared to listen to what they said.

When the Calcutta riots started in 1946 -- they were the first riots really; before that there were killings, but not riots as such -- Gandhi went to Calcutta. He fasted and stopped the rioters.

These leaders had sacrificed so much that nobody could doubt their integrity.

When these riots were going on, the armies on both sides were busy protecting the trains and they continued to be friendly.

There was no animosity or hatred between one unit of the Indian army or a unit of the Pakistan army.

The armies and civil servants helped the governments maintain order.

It was only later, under Zia-ul Haq, that the Pak army became radicalised.

I did a course in the US with a Pakistani army officer in 1961. I still have 2, 3 photographs of him.

'To sustain freedom, you need a Constitution'

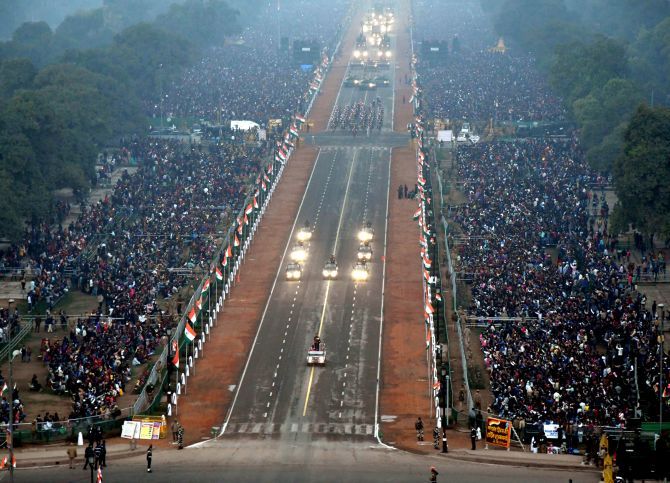

I have often thought why Republic Day was given precedence over Independence Day.

At 18, I thought Independence was the first step and hence the most important, but in retrospect I realised that to sustain freedom, you need a Constitution.

A law to keep the integrity and security of all who have a stake in that society.

Look at American history, they got independence but a civil war followed because they did not have guiding principles and a law under the constitution to keep the nation together.

Our biggest problem has been keeping this country together.

Nation building is never easy. It is a very difficult task. Even 70 years is not too long a time.

INDIA 70 SPECIALS

© 2025

© 2025