'If a doctor is kind of trying to say that there's an urgency, relatives should definitely get a second opinion.'

Respirologist Dr Lancelot Pinto, from the start of the pandemic, has been diligently and conservatively putting out information, whenever he can, via media interviews and through his Twitter feed, on the correct medical protocol for COVID-19 treatment.

An epidemiologist and consultant pulmonologist at the P D Hinduja Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mahim, north central Mumbai, in Part I, he provided a four-point checklist that could help you decide if you need to seek hospital admission or not, if you have caught the disease.

In the vast majority of cases hospital admission is not required, stressed Dr Pinto.

In Part II, Dr Pinto puts forward some facts on the drugs prescribed for COVID-19 and how much of a say the patient or his relatives have in their administration. He also explains to Vaihaysi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com why staying at home is often the best option.

Why you should not admit your COVID-19-ill relative if s/he is not showing any of the red flags on Dr Pinto's four-point checklist:

"I tell people that, if you're having a loved one get admitted to be monitored it, may not be in their best interest. You are isolating them from the rest of the family. It's a very scary place to be at," he says.

"If you go by the book -- I go by the book and at my hospital, we tend to go by the book -- if somebody gets admitted early on, we pretty much admit them and just monitor them, you are not giving them anything in terms of drugs.

"If you can manage that kind of monitoring at home, why would you not want the person to be in a familiar environment with your loved ones around you, rather than be in an isolating hospital."

If you have a choice, be careful to choose either a private or a public hospital with a good COVID-19 care track record

Once your relative is in the hospital, their care -- good or bad -- is beyond your control. So, opt, if you can, for a hospital and an attending physician you can trust for yourself or your COVID-19-ill relative, while/when you have a choice and beds are not scarce.

Dr Pinto: "The way COVID-19 is, there is a great deal of trust that is part of the equation, once a person gets admitted. You are not going to be able to get a second opinion, for example, that easily."

"You are not going to be able to have a clinician -- somebody from another hospital visit and oversee, or get another opinion. You will have to intrinsically trust the system (at the admitting hospital).

"That's the case, unfortunately, the world over -- everyone wants to limit exposure. You wouldn't want multiple doctors going in; you wouldn't want anybody who's not needed to go in, right? It's a very controlled situation in that sense, which will take a lot of trust.

What say does a patient or her/his relatives have in her/his treatment (for tests, expensive medication or second opinions)

How should relatives or the patient handle decisions a hospital plans to take?

These decisions could be to administer certain very strong or expensive drugs. Or for a new course of treatment. Or for special tests.

What questions should relatives ask.

Are second opinions, by phone, possible, even in a fast-moving situation like an attack of COVID-19?

Confirms Dr Pinto: "(Speaking to another doctor or two, before relatives or a patient okays a medication) is an option.

"At least at my hospital, that's always an option. Like I don't think anybody holds back from (allowing a patient to) seeking a second or a third opinion. That's never an issue. Again, if you talk about my hospital, there's transparency -- we have iPads on the floor. We click photographs of the patient's notes, etc and send it to the patient's relatives, if they want to show it to somebody else.

He further clarifies: "Unless a person is in the ICU, most decisions that are made for medicines for COVID-19, don't have a very short window. It's not like a few hours generally.

"As a take-home point, there is never an emergency where you have to make a big decision about a medication within half an hour or within 45 minutes or something like that. As a broad rule, a 24-hour window should be okay to make major decisions for most things in COVID-19, especially when the person is not in intensive care.

"In intensive care, it's a different story altogether. If somebody had a pneumothorax (collapsed lung), for example, if a tube has to be put in that needs to be done soon.

"In the ward, especially as far as the expensive drugs etc are concerned, if a doctor is kind of trying to say that there's an urgency, relatives should definitely get a second opinion. Even, for example, for Regeneron it's a seven-day window, from the point of infection, or from when your symptoms start manifesting."

"So, it's never like: Give it now or never. If a doctor is doing that, then yes, I would definitely (take a second opinion).

About the right of a patient or his relative to enquire about the purpose or reason for a test: "Absolutely. It's a patient's right to ask those questions. It's a doctor's responsibility to kind of explain himself or herself to the patient as well. I don't think it can ever be didactic or paternalistic in that sense. I don't think that's the right way. But I do know that there are doctors out there who don't necessarily encourage questions."

But Dr Pinto goes on to explain that correct patient care protocol may get neglected in many hospitals when doctors, hospital staff and hospitals are overburdened by too many COVID-19 cases.

In pre-COVID days, when a doctor was on his rounds -- "the questions get asked, the answers are given, that conversation happens a lot more" about the planned medical course of action -- and would happen with the patient or family at the patient's bedside.

That's not to say, as per Dr Pinto's standpoint, that even in a COVID-19 situation, a patient or his relatives should not insist on knowing the exact reason for a special medicine being administered or an important test, like a CAT scan, being done.

"For the administering of the COVID-19 drug Regeneron, for example, I deal with this on a daily basis. I kind of lay out the scenario in terms of probabilities in front of the person and the person makes an informed choice.

"But that may not be how medicine is always practiced in the country. We all know that there are shortcomings in communication -- sometimes in terms of how things are told or how (the manner in which) people are just offered a choice.

The root cause for that "the badly skewed doctor-patient ratios" and doctors see too many patients on a daily basis.

Dr Pinto adds: "The lack of time sometimes makes it very difficult to have a detailed conversation on risk versus benefits. This is not a perfect situation for sure and I'm not condoning it. But as a person working on this side of the fence, it's difficult to have a detailed conversation, when you are handling something like 20 patients in a ward, and you are making phone call after phone call to every relative, and at the same time, you are running your own practice."

"None of us had added hands on board when it came to COVID-19."

The COVID-19 positive can come home from the hospital:

As Omicron case numbers mount, like it happened with Delta in the second wave, there will be many people who are admitted to a hospital for some other illness/treatment/child birth, who could turn out to be COVID-19 positive too

Dr Pinto's advice: "If the primary illness has been sorted out, then just because they turned out COVID-19 positive in the hospital, shouldn't be a reason to unnecessarily prolong their stay. Encouraging people to take their family members home is important."

Even if relatives can take the patient home, they may be prevented from doing so, in Mumbai, for instance, perhaps by BrihanMumbai Municipal Corporation rules, or by housing society rules or lack of capacity to care for the person.

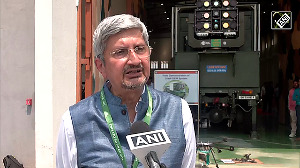

IMAGE: Dr Lancelot M Pinto. Photograph: Kind courtesy Dr Lancelot M Pinto

IMAGE: Dr Lancelot M Pinto. Photograph: Kind courtesy Dr Lancelot M PintoHow can you reduce hospitalisation costs

Treatment costs for COVID-19 can be astronomical at private hospitals. Medical insurance coverage runs out and patients go out of pocket handling hospitalisation expenses.

The best option available is to opt for a public hospital. Numerous city municipal corporations opened special COVID-19 care centres during the pandemic and some of the city public hospitals considerably upgraded their standards of treatment.

Many of these special COVID care centres, especially in Mumbai, are world-class and are doing a great job. "Absolutely," confirms Dr Pinto. "A lot of people have been managed in these hospitals, like in Mumbai, there is Seven Hills, a huge government hospital managing COVID-19 patients and the jumbo centres have ICUs, as well."

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025