Sheela Bhatt reports from Firozabad, the country's centre for glass bangles, on what life is like for its workers in the wake of the lockdown.

Photographs and videos: Sheela Bhatt.

From Agra I drive down to Firozabad, an industrial city in Uttar Pradesh famed for its decades-old business of chudiyas (glass bangles). The city sustains more than 800,000 people directly and indirectly in the age-old business of making glass bangles.

In highly inhuman conditions, amidst unbearable heat, poor workers make glass bangles that are supplied all over India.

Every other household in the poorer localities of Firozbad is involved in making bangles. At Shyam Nagar in Karbala, Vinod Kumar is sitting in an open area outside his home.

"Shyam Nagar is a 100 per cent chudiya kamgar colony. Yahan log roz kamakar roz khate hain (we are all daily wage earners). Everybody works on an hourly basis," says Vinod Kumar.

"Our income is based on buffing bangles. Our entire family is engaged in the bangle industry. To all of us, this lockdown is unbearable, unsustainable. On a regular day, we skip lunch even, because the more we heat two ends of bangles the more we earn."

Seeing us speak, more than 30 people encircled us in no time.

Looking at my concerned expression, Vinod Kumar says there is no social distancing inside the colony.

"Ghutan hoti hai (it feels claustrophobic)," one woman says.

Het Singh, who works for the Samajwadi Party, is unhappy with the UP government. "Since the lockdown, no sarkari officer has entered our colony. We have 8,000 voters in the area, and more than 5,000 work in bangle factories or earn from it," says Singh.

"Chakka jam hai, majdoor pareshan hai (the factories are closed, workers are troubled). I met our area's additional district magistrate to give us rations. He said the ration supply will start after the survey," Singh adds.

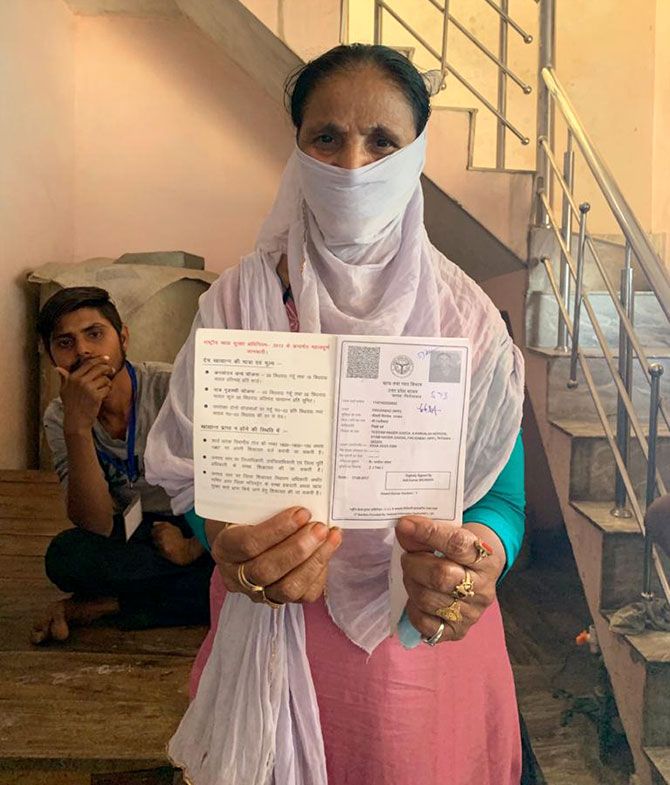

Mithilesh, below, shows me how, four months ago, the government without notice cancelled her ration card.

A widow, she asks, "How will I get the ration provided by the government now? With no work, I don't have money even to buy milk."

Everyone in Shyam Nagar is angry with local traders who, they allege, sell milk and foodstuffs at hiked prices.

Mithilesh's son Govind is worried about another issue.

In the cities, particularly in New Delhi, people were extremely disturbed to see visuals of migrant labourers at the Anand Vihar bus stand after the lockdown was enforced.

On the other hand, the same visuals have created tension in UP, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar.

Govind, speaking from inside his home, says, "They should not have been allowed to leave Delhi. The government should have been strict with them. Only after a medical check-up should they have been allowed to visit their villages."

"But what would they eat in Delhi without a job? They would have remained hungry," I tell him. "Even neighbours don't help in Delhi."

Govind, a young man who is engaged in bangles buffing and earns Rs 200 daily, cuts short my argument.

"Bhukha toh pura desh hai! Bhukh kahaan nahi? Bhukh gaon main hai, kasbe main hai. Har jagah bhukhmari paida hui hai (the entire nation is hungry, where is there no hunger? Hunger is there in villages, in districts. Everywhere, hunger is an issue)," he says.

"Aadhi roti kha lete. Shahar main hi rehna chahiye tha. Coronavirus ka dar toh hai (they should have eaten a little less in Delhi, but stayed back. There is a real fear of coronavirus)."

"Coronavirus se nahi toh bhukh se mar jayenge. Hamara chudiyo ka kaam sharu karva dijiye (if not from coronavirus, we will die of hunger. Please help us restart our work of buffing bangles)," says a woman who has joined the discussion.

The UP government, they say, is giving food packets in some areas, but that is only for lunch. What would families eat for dinner?

All of them are unanimous that if they get free grain and edible oil through the public distribution system, if the government opens community kitchens for the poor, only then will the villages and towns of India survive the lockdown.

"We find this time more difficult than demonetisation. We have a fear of health. We are afraid of coronavirus," says Het Singh. "But we have a family to feed too. At the time of notebandi poor people were allowed to walk on the roads. We got less work then, but we did some work."

"Yeh shanti to samajh hi nahi aati (this silence is incomprehensible)."

© 2025

© 2025