'It is advisable for Indian interlocutors to follow the Chinese tactic of repeating the Indian position, both for the record and to test the Chinese negotiator's resolve and intentions.'

A revealing excerpt from former foreign secretary Vijay Gokhale's The Long Game: How the Chinese Negotiate With India.

One of the favourite moves in the Chinese playbook is to play upon the emotions of the Indian interlocutor.

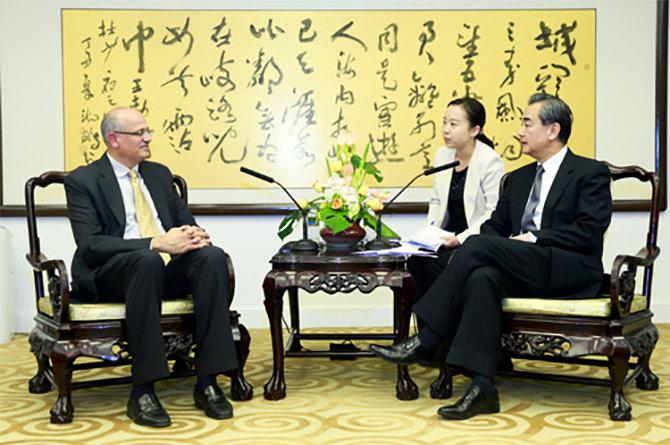

The Chinese head of delegation will indulge in flattery by telling her or him that they are an 'old friend' (lao pengyou in Chinese) of China.

This is intended to make the opposite negotiator not only feel special but also obligated to be sympathetic to the Chinese.

It almost always succeeds. The trick works best on Chinese home ground.

The Indian interlocutor is told that the venue for the talks or the banquet has been specially selected for her or him, or that the Chinese leadership knows how influential the individual is in her or his government, or that the interlocutor speaks the Chinese language just like a Chinese.

In rare cases, they 'break' protocol by granting a higher level of meeting than is usually warranted, to make the Indian interlocutor feel as if she or he is highly valued by the Chinese side.

The Indian negotiator is also flattered if the Chinese bestow a Chinese name upon her or him, usually consisting of Chinese characters with exotic meanings that are usually not used by the Chinese themselves.

The Chinese hospitality can be beguiling and, often, intoxicating as well, and the idea is to soften up the Indian negotiator.

Richard Solomon, who wrote an analysis of Chinese negotiating behaviour on the basis of the experience of US negotiators in the 1970s, said that the purpose of friendship that the Chinese offer to a foreign interlocutor is to manipulate feelings of goodwill, obligation or dependence to achieve their negotiating objectives.

At the commencement of the negotiations, the Chinese always invite the other side to talk first.

This, again, appears to demonstrate their graciousness and civility, but it is in fact intended to get the other party to lay out all its cards on the table first.

Once the Indian side has laid out its positions, the Chinese side asks questions or seeks clarifications, all with a view to having a clear idea of India's negotiating position before they reveal their cards.

It might be worthwhile for the Indian side to consider following a similar practice whenever the negotiations are held in India.

On any contentious issue, the Chinese side routinely follows the practice of enunciating 'principles' before tackling an issue in detail.

This lies at the very heart of the Chinese negotiating strategy.

If the Chinese suggest that both sides should first work out agreed principles, it should be seen for what it is, as the Chinese 'setting out the chessboard'.

Since principles are esoteric and general in nature, the Indian interlocutor is usually impatient to move towards a resolution of the matter, and tends to agree to the Chinese proposals. This is a mistake.

China uses 'principles' to create the framework for settling an issue in such a way as to build in China's core positions and to constrain the Indian side's negotiating flexibility when the specifics are discussed. In this process, China also always leaves a way out for itself, so that if they need to change their position, it can be explained in terms of the principle, and to avoid the embarrassment of making a U-turn.

The Indian side might, therefore, wish to closely examine the 'principles' proposed by China, and negotiate them in a manner that limits Chinese flexibility or does not allow the Chinese side to constrain India's position on the specifics of any issue.

If the Chinese are not able to secure their 'principles' early on, they use several tactics to goad the Indian side.

One tactic is to allege that the Indian interlocutor is not being faithful to the 'consensus' agreed at the leadership level.

The Chinese play on the sense of guilt to dampen the resolve of the Indian negotiator to negotiate the principles.

Another tactic is to question the interlocutor's sincerity.

The Chinese side will claim that the Indian interlocutor is not being constructive and may be the cause for the breakdown of talks.

This is an intimidatory tactic that puts the fear of failure into the Indian negotiator's mind and keeps her or him under psychological stress.

Yet another tactic is to demand explanations for things the Indian side may have said or done.

This is a form of harassment or 'shaming' that is aimed at embarrassing the Indian head of delegation in front of his or her delegation.

The Chinese also use threat as a form of psychological pressure.

Their usual tactic is to refer to unspecified consequences if India does not relent to the Chinese side, with the further caveat that the Indian side shall be responsible for the Chinese retaliation that follows.

Once the principles have been secured, the Chinese will enter into discussion on the specifics.

It is common for them to use incremental nibbling techniques (also known as salami-slicing).

This enables the Chinese to secure concessions from the opposite number at each step, usually leading up to substantive results when the final agreement is concluded, but without taking excessive risks at any point.

Paying close attention to the setting of the agenda could help avoid this situation.

Discussion on the specifics, in a step-by-step way, is usually a painful process.

The Chinese side tends to repeat its positions ad nauseam on each point.

This has two benefits. It establishes a 'record' for the future, and it wears down the Indian interlocutor in order that she or he may bring up alternatives simply to break a 'deadlock' which the Chinese have deliberately created.

Thus, it also serves the purpose of determining the opposite side's limits of flexibility or bottom line on an issue.

While the repetition of positions by the Chinese interlocutor has to be accepted by the Indian side, when the Indian side resorts to this kind of tactic, the Chinese side will allege that the Indian negotiator is faithless, dogmatic or unreasonable.

A favourite allegation that is levelled by the Chinese side is that the Indian side is not 'meeting us halfway'.

It is advisable for Indian interlocutors to follow the Chinese tactic of repeating the Indian position, both for the record and to test the Chinese negotiator's resolve and intentions.

One tactic used by the Chinese side is to reverse a complaint.

Thus, when the Indian interlocutor complains about Chinese action on the Line of Actual Control or certain Chinese actions in multilateral situations that are viewed negatively by India, the Chinese will make the same complaint against India.

The purpose is to blur the distinctions and to thus neutralize Indian 'asks' without addressing the specific concern at all.

On issues that are particularly contentious or important, it is vital to be mindful of two sorts of Chinese plays.

They will keep saying 'no' for as long as possible and, by doing so, keep all options on the table.

These include options that do not exist, such as refusing to recognise Sikkim as a part of India when the rest of the world had already done so and China had no means of changing the ground realities.

The purpose of saying 'no' to all the proposals made by the other side is to frustrate the Indian interlocutor to the point that she or he agrees to move on a step-by-step basis.

This gives the Chinese greater opportunities to extract concessions at each step.

An American negotiator who spent many days with the Chinese in trade negotiations had this to say: 'In the end what mattered more than logic, facts or force of argument was that, as the negotiations had begun, the US delegation placed the "loaded gun" of trade retaliation on the table and pointed to it occasionally...'

The option of ending a negotiation without a result should, therefore, always be available to the Indian negotiator.

The threat of walking out of the talks should be used only when the state of play is overwhelmingly to India's advantage.

The other Chinese play is to fall back on the power of silence.

This is a particularly dangerous weapon in the Chinese negotiating arsenal to which the Indian side has succumbed many times.

If there is no response from the Chinese side to an Indian proposal or contention, it would be fatal to presume China's acquiescence or acceptance of the idea.

China uses the power of silence in two instances -- if it wants to keep its real intentions hidden or if it wants to avoid taking a position.

This is grand deception. At any subsequent time, the Chinese can reverse course, and they have done so on many issues of importance to India, including the boundary question and India's sovereignty over Jammu and Kashmir.

It is critical that the Indian interlocutor not only should not presume that China's silence is tantamount to acceptance of the proposal, but it should also sound the alarm because China might be playing the deception game.

Therefore, the Indian interlocutor must also reiterate the Indian proposal more than once for the record in order to make it clear to the Chinese side that it has not fallen for the Chinese trick of silence.

Excerpted from The Long Game: How the Chinese Negotiate With India by Vijay Gokhale, with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House India.

© 2025

© 2025