On November 18, 1962, 114 soldiers of the 13th Kumaon fought till the last man, and last bullet, in sub-zero temperatures, to beat back the huge Chinese army.

We salute the Heroes of Rezang La.

India may have lost the 1962 war with China, but it was not completely a saga of defeat.

Hamstrung by an indecisive leadership and poor military equipment, the Indian Army put up a valiant resistance along the McMahon Line. It is another matter the political leadership of the day did not back them.

One such spot where our soldiers fought back, and repelled, the Chinese incursions was at Razang La near Chushul, in the Himalayan heights.

On November 18, 1962, 114 soldiers of the 13th Kumaon fought till the last man, and last bullet, in sub-zero temperatures, to beat back the huge Chinese army.

A grateful nation acknowledged their valour by posthumously conferring the Param Vir Chakra on Major Shaitan Singh.

Seven years ago, Tarun Vijay -- later a BJP member of Parliament -- undertook an emotional journey to Chushul and Rezang La, site of a memorial to commemorate the brave souls who died so we may live in peace and security.

On the 55th anniversary of the heroic counter-offensive by 13th Kumaon, we republish Tarun's feature.

'Sir, a national crisis has been created as a result of the Chinese attack on the northern border. China has expansionist designs, it has set its eyes like a vulture on 48,000 square miles of land belonging to India.

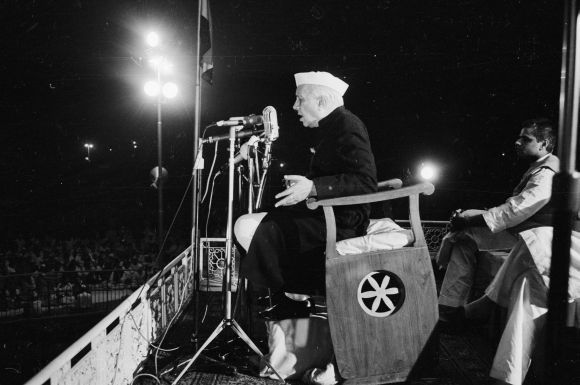

'On August 25, 1959, while speaking on the Kerala debates the prime minister (Jawaharlal Nehru) had stated that India would not remain India if per chance it becomes Communist. The same thing applies to China as well.

The defence minister (V K Krishna Menon) has a doubtful past and his present conduct is dubious. He has Communist leanings. In his message on the Territorial Army Day he said that India should not keep a large army because keeping a large army was not compatible with our morality.'

-- Atal Bihari Vajpayee in the Lok Sabha, December 22, 1959

The ironies of history take strange shapes.

In 1962, Nehru didn't listen to the warnings of the erstwhile Jana Sangh, believed 'the Chinese can never attack us' and lost face and land both to his 'bhai'-like friends.

Then the government arrested more than 400 top Communist leaders on charges of sedition and invited volunteers of the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh to participate in the 1963 Republic Day Parade at Rajpath in New Delhi in full uniform, recognising its services during the war.

Can the nation forget the 1962 war? Who were those who fought and died? For who? And to what avail?

One of the stories India can never forget is the battle we fought in the Indus valley, near Chushul village.

The battle of Rezang La, fought at an altitude of 17,000 feet, is one of the most incredible sagas of valour and courage that Indian soldiers have showed.

That was November 18, 1962. They fought and died for Indian soil.

The question remains still unanswered: Why did we have to fight a war, and why was it that the brave 114 soldiers of the 13th Kumaon had to offer their supreme sacrifice fighting till the 'last man and last bullet' in sub-zero temperature (minus 15 degrees Celsius) at Rezang La on November 18, 1962?

What were the causes of that war and what happened afterwards?

Who remembers them except a few ex-soldiers and the patriotic crowd at Rewari (Haryana), hometown of most of the martyred Ahirs who had fought at Rezang La?

Why does no politician think it a matter of honour to send his children to join the army?

Why do we have an important road in Delhi named after Krishna Menon, the disgraced defence minister of the '62 war, and nothing significant to honour the men who gave their lives to save India in Chushul?

These were the thoughts in my mind when I set out for Chushul to get a feel of 'November in Rezang La' and pay my homage to the bravehearts.

The 1962 war with China is a sad story of a completely incapable leadership, favouritism at the top echelons of the army, and a disregard of the nation's security needs by those who were hailed by the people as their saviours.

Neville Maxwell, a British journalist, writes in his famous book India's China War: 'At the time of independence, (B M) Kaul appeared to be a failed officer, if not one disgraced. But his courtier wiles, irrelevant or damning until then, were to serve him brilliantly in the new order that independence brought, after he came to the notice of Nehru, a fellow Kashmiri Brahmin and, indeed, distant kinsman.'

Not only did he hold the key appointment of chief of general staff but the army commander, Thapar, was, in effect, his client.

Kaul had, of course, by then acquired a significant following, disparaged by the other side as 'Kaul boys', and his appointment as CGS opened a putsch in HQ, an eviction of the old guard, with his rivals, until then his superiors, being not only pushed out but often hounded thereafter with charges of disloyalty.'

Those who didn't know their men, their land and the risks involved called the shots, yet our bravehearts stood firm for the honour of their motherland.

The Rezang La battle saga is among the most inspiring stories of soldiers dying in the line of duty, yet our schools, which proudly prescribe the age-old narration of Romulus and Remus, find it unworthy to insert a lesson on how India was defended at Rezang La by Indian soldiers of the 13th Kumaon.

They were ill-equipped, ill-prepared and heavily outnumbered by the Chinese. All the 114 jawans died in action, not a single soul retreated and neither did they let the Chinese intrude.

For three months the government didn't know about them, about their extraordinary sacrifice, till in January-end in 1963, shepherds from Chushul found bodies of jawans scattered on the Rezang La, after the snow had melted.

The dead bodies of the Chinese were far more in number, about eight hundred on our side, and it was estimated that more than a thousand might have fallen to the bullets of Indian soldiers.

It was an unbelievable feat and the government decorated Major Shaitan Singh with a Param Vir Chakra, posthumously.

The Param Vir Chakra citation awarded to him reads: 'Major Shaitan Singh was commanding a company of an infantry battalion deployed at Rezang La in the Chushul sector at a height of about 17,000 feet.'

'The locality was isolated from the main defended sector and consisted of five platoon-defended position. On 18 November 1962, the Chinese forces subjected the company position to heavy artillery, mortar and small arms fire and attacked it in overwhelming strength in several successive waves.'

'Against heavy odds, our troops beat back successive waves of enemy attack. During the action, Major Shaitan Singh dominated the scene of operations and moved at great personal risk from one platoon post to another sustaining the morale of his hard-pressed platoon posts.'

'While doing so he was seriously wounded but continued to encourage and lead his men, who, following his brave example fought gallantly and inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy.'

'For every man lost to us, the enemy lost four or five.'

'When Major Shaitan Singh fell disabled by wounds in his arms and abdomen, his men tried to evacuate him but they came under heavy machine-gun fire. Major Shaitan Singh then ordered his men to leave him to his fate in order to save their lives.'

'Major Shaitan Singh's supreme courage, leadership and exemplary devotion to duty inspired his company to fight almost to the last man.'

The battle fired the imagination of young soldiers and Bollywood alike. A successful movie, Haqeeqat, based on the Chushul saga was made by Chetan Anand starring Dharmendra and Balraj Sahni.

I was on my way to visit the same area, the village called Chushul and the Rezang La memorial, in the month November, 46 years after the battle had taken place.

The journey to Rezang La was the most scintillating pilgrimage for me, like the Kailas Yatra.

Interestingly, the best route to Kailas also goes through Chushul and connects Demchhok (on the Line of Actual Control, within Indian territory) to Nyari province of Tibet, running alongside the Indus river.

There has been a long-standing demand from Ladakhis, supported by J&K leaders like Dr Farooq Abdullah, to have this route opened for the Kailas Yatra.

The 80-minute flight from Delhi to Leh is itself a memorable one, and passes over Manali, the Rohtang pass and snow-clad mountains before touching down at Kushok Bakula Rinpoche airport, Leh.

The outside temperature was minus eight degrees and I straightway drove to a friend's house for a couple of hours of acclimatisation. At an altitude of 11,000 feet, it's mandatory to acclimatise before moving to another destination, and any violation may prove fatal.

'No Gama in the land of Lama', says the Border Roads Organisation's roadside advisory, meaning don't show undue haste and bravado in this land of high mountains and Buddhist lifestyle.

It would be seven hours to Chushul, said my guide Dorjey while putting my rucksack into the Innova. We left Leh early morning and passed through Stakna, the summer palace, Thikse Gompa, Sindhu Darshan, Upshi, Hemis Gompa, Karu and negotiated the tough Chang La Baba pass at 17,800 feet, saying hello at Chemday monastery.

At Chang La jawans offer a cup of 'love tea' free to all travellers -- a kahva with cashew nuts and roasted almonds. It's really invigorating.

Next was Tsoltak, and Luking was a further 65 km and Chushul another 124 km away.

Post Chang La, a continuous descent along the Tangtse took us to the breathtaking expanse of a mesmerising empire of salt water called Pangong Tso lake.

It's a magic God created for the gods. Tourists are allowed only up to this point, and all non-resident Indians need an Inner Line Permit issued by the district magistrate, Leh, to enter this area.

The lake is 134 km long and five km wide. Another 40 km, alongside this blue, turquoise green world of water, and we will be at Chushul.

The road is really a patchwork of scattered stones and pebbles, though a board announces that the Luking-Chushul road is under construction.

A little before dusk we finally arrived at Chushul, which looked every bit a sleepy, dreamy-eyed village. It has a population of 993 persons to be exact, as informed by its 'numberdar'.

The wind was getting wilder by the minute. It was chillingly cold outside and it seemed almost impossible to push the shutters of the camera with bare fingers, frozen and numbed they were.

At 4 pm the wind got ferocious and the waves it created in the lake were great fun to watch.

Chushul has hardly changed since 1962. There is no electricity, though solar power connection is given to the villagers with a dose of subsidies.

"But we can't run colour TVs on that low voltage connection," complained the villagers. Lights are off early, usually there is only one bulb lit in each home, for cooking, evening gupshup and studies for the kids.

So the usual schedule is to have a heavy peg of local rice brew, early supper and go to sleep. The dependable sources of news are transistors and B&W TVs, with Doordarshan's unchallenged monopoly. Though a few enterprising households have bought Dish TV receivers, and access other channels.

I had hardly taken the prescribed and mandatory rest at Leh, so the dreadful headache began at a deadly pace and soon the world turned colourless to me.

The wintry chill coupled with a lack of oxygen, and horrific wind, made my task truly 'adventurous'. I cursed myself at leaving the comforts of electioneering in Delhi and other states to reach a place that no one even thinks about in winter.

Suddenly 1962 flashed before my eyes.

It's 2008, we have better woollen jackets, comfortable sleeping bags, well-connected communication system, a strong political Opposition and an awakened and vocal leadership in the forces. But 1962 was different.

Ill-equipped jawans, bad communication system hardly worth its name, poor clothing; the Chinese attacked in this very month, in this chilly winter, in the wee hours of the day.

In a such sub-zero atmosphere I was unable to operate my camera, but they had to operate .303 guns, fire mortars and keep fighting! I was at a lower level in the village with comparatively warmer temperature.

They were at the top of Rezang La, facing Trishul, at 17,000 feet. They defeated death and kept the flag high, but New Delhi forgot them and sang in praise of the defeatists.

Do the inhabitants of Chushul remember that story, I asked with excitement and waited for a reply. No one could say yes or recount what perhaps was told by his father or grandfather.

There is hardly any remembrance of the battle the nation feels so proud of, in this village which once stood as the 'sword of the nation'. The army's valour has hardly been passed on to the villagers, to the new generation.

Like an unconcerned machine, some men in uniform come to the Rezang La memorial every year, perform rituals and go away. Without touching the lives of those locals who carry the burden of that great legacy.

It's a hundred percent Buddhist village and there is a permanent complaint that no one visits them from Delhi -- no politician, no minister has ever spoken to them about their lives and demands.

Sometimes a minister comes in an army helicopter, stays with the army officers and goes back immediately. An old village monk told me in the morning that his grandpa used to tell him stories about how they had brought the dead bodies of the Rezang La warriors from the mountaintop That's it. Nothing more.

Even the village doesn't celebrate November 18, Rezang La day.

"Sir," Sonam said, "before the Chinese attack in 1962 Chushul was the sub-divisional headquarters and the sub-divisional magistrate used to have his office here. He was shifted after the war, and it's causing great difficulty to the villagers."

The village depends solely on the army for everything; still the cordial touch is missing. It's too mechanised.

Do our soldiers at the mountaintop observation posts have heated bunkers to keep better watch on Chinese activities, I asked Sonam and the sarpanch. No one could answer. Perhaps I had asked a foolish question.

But the villagers had a lot to say. The Chinese look at them with contempt, and in flag meetings with their Indian counterparts they complain about how the Chushul villagers and shepherds often 'violate' the Line of Actual Control.

A dose of Paracetamol helped and the morning was a little comfortable. We set out for the Rezang La memorial at 6 am, bidding adieu to a hallowed village. I was thrilled and felt I should have taken some flowers to lay as a wreath at the memorial. But nothing was available.

Having taken the turn from Chushul, at every second mile I saw a board put up by the army showing the direction and miles to the memorial.

Dorjey indicated the beautiful Trishul mountains on my left, bathing in the first rays of a nascent sunrise. The fields are vast and grand, we were cruising in a sea of openness, roads are either invisible or it's a sporty challenge to you to create your own path!

Yet the danger looms large as the heights on our left are under Chinese control and they monitor our activities comfortably.

The Rezang La memorial is a simple marble pillar with names of all the 114 martyrs etched on two sides, in Hindi and in English. The third side has these inspiring words:

How can a Man die better than facing Fearful Odds,

For the Ashes of His Fathers and the Temples of His Gods,

To the sacred memory of the Heroes of Rezang La,

114 Martyrs of 13 Kumaon who fought to the Last Man,

Last Round, Against Hordes of Chinese on 18 November 1962.

Built by All Ranks 13th Battalion, The Kumaon Regiment.

This is a lightly edited version of the article first posted on Rediff.com in 2008.

© 2025

© 2025