Photographs: US Air Force Photo

It took one bomb to change the course of the Second World War. It took one bomb to obliterate an entire city and its residents. It took one bomb to redefine the meaning of the term super power.

Time stood still in the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, when the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, 'Enola Gay', piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets of the 393d Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, of the US Air Force, dropped the first atomic bomb to be used as a weapon.

The Hiroshima bombing left 80,000 to 140,000 people killed and 100,000 were seriously injured. The Nagasaki bombing killed 74,000 people and left 75,000 seriously injured.

Sixty-five years on, rediff.com reflects on the day 'Little Boy' unleashed havoc on Hiroshima.

When the clock stopped ticking in Hiroshima

Photographs: US Air Force photo

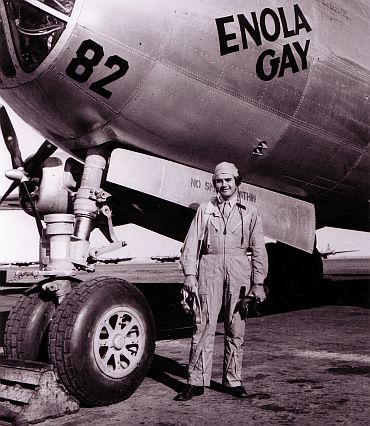

This photo taken in 1940 at the Roswell Army Air Field in New Mexico shows Col Paul Tibbetts, Jr posing in front of his B-29 Superfortress 'The Enola Gay' (named for his mother).

'The Enola Gay' is the same plane he piloted when his bombardier dropped the first atom bomb over Hiroshima.

When the clock stopped ticking in Hiroshima

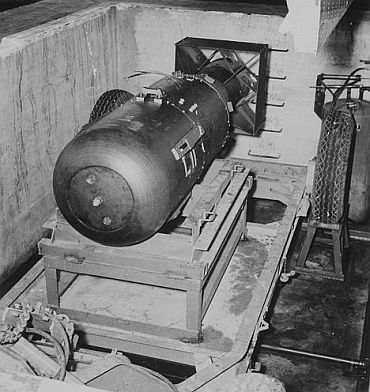

Image: The 'Lttle Boy'Photographs: US Air Force Photo

'Little Boy', the codename of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, was developed as part of the Manhattan Project during World War II.

It derived its explosive power from the nuclear fission of uranium 235.

Approximately 600 milligrams of mass were converted into energy. It exploded with energy between 13 and 18 kilotons of TNT (estimates vary) and killed approximately 140,000 people.

When the clock stopped ticking in Hiroshima

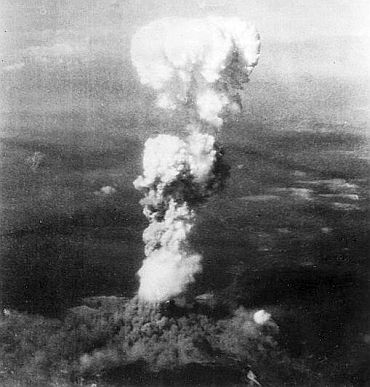

Image: The Hiroshima mushroom cloud, through a window in one of the three B-29s, which went on the bombing run.Photographs: US Air Force Photo

The bomber flew at low altitude on automatic pilot before climbing to 31,000 feet as it neared the target area.

At approximately 8:15 am, Hiroshima time, the Enola Gay released Little Boy, its 9,700-pound bomb, over the city.

Forty-three seconds later, a huge explosion lit the morning sky as Little Boy detonated 1,900 feet above the city, directly over a parade field where soldiers of the Japanese Second Army were training.

When the clock stopped ticking in Hiroshima

Image: The Enola Gay lands at the island of Tinian after the bombingPhotographs: US Air Force Photo

Though already eleven and a half miles away, the Enola Gay was rocked by the blast.

At first, Tibbets thought he was taking flak. After a second shock wave (reflected from the ground) hit the plane, the crew looked back at Hiroshima.

"The city was hidden by that awful cloud . . . boiling up,mushrooming, terrible and incredibly tall," Tibbets recalled.

When the clock stopped ticking in Hiroshima

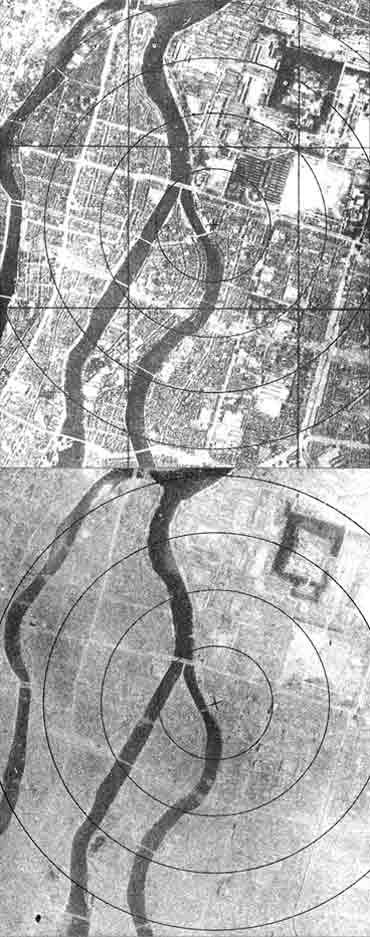

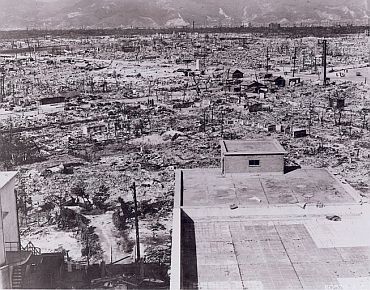

Image: Photos taken before (above) and after the Hiroshima bombing.Photographs: US Air Force photo

Nearly every structure within one mile of ground zero was destroyed, and almost every building within three miles was damaged.

Less than 10 per cent of the buildings in the city survived without any damage, and the blast wave shattered glass in suburbs twelve miles away.

The numerous small fires that erupted simultaneously all around the city soon merged into one large firestorm, creating extremely strong winds that blew towards the centre of the fire.

The firestorm eventually engulfed 4.4 square miles of the city, killing anyone who had not escaped in the first minutes after the attack.

When the clock stopped ticking in Hiroshima

Image: Photo taken from the top of the Red Cross Hospital in Hiroshima looking northwest shows the destructionPhotographs: US Air Force Photo

Those closest to the explosion died instantly, their bodies turned into black char.

Nearby birds burst into flames in mid-air, and dry, combustible materials such as paper instantly ignited as far away as 6,400 feet from ground zero.

The white light acted as a giant flashbulb, burning the dark patterns of clothing onto skin (right) and the shadows of bodies onto walls.

When the clock stopped ticking in Hiroshima

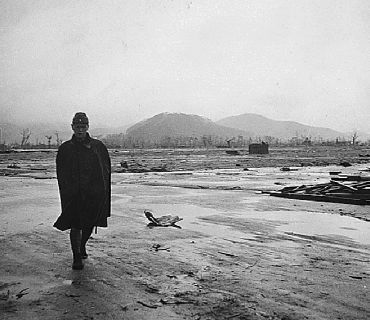

Photographs: US Air Force Photo

People farther from the point of detonation experienced first the flash and heat, followed seconds later by a deafening boom and the blast wave.

The first confirmation of exactly what had happened came only 16 hours later with the announcement of the bombing by the US.

Several days after the blast, however, medical staff began to recognise the first symptoms of radiation sickness among the survivors.

Soon the death rate actually began to climb again as patients who had appeared to be recovering began suffering from this strange new illness. Deaths from radiation sickness did not peak until three to four weeks after the attacks and did not taper off until seven to eight weeks after the attack.

When the clock stopped ticking in Hiroshima

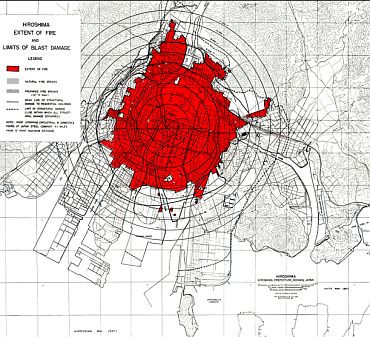

Image: Map of Blast and Fire Damage to HiroshimaPhotographs: US Strategic Bombing Survey

Survivors on the edge of the lethal area and beyond suffered injuries from radiation.

Some temporary survivors died soon afterward due to acute radiation sickness, but most of the radiation effects are evident only statistically, as increases in the incidence rates of cancer, leukemia and certain non-cancer diseases over the lifetimes of the survivors and their children who were exposed in uterus.

To date, no radiation-related evidence of heritable diseases have been observed among the survivors.

article