In October 2003, I wrote an article Diverting the Brahmaputra: a Declaration of War. At the time, I was told that it was a cheap journalistic gimmick; there was no 'scientific' proof!

My question then was: "What is the rationale for the project?" My answer was that the two most acute problems faced by China were food and water.

Seven years later, these issues are more acute than ever: Water is a rarer commodity in China and agriculture needs more water to sustain the increasing requirements of a wealthier population.

Twenty years ago, this led Chinese experts to look around for water. The answer was not far: Tibet is the water tower of Asia. About 90 per cent of the Tibetan rivers runoff flows downstream to China, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, Thailand, Burma, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Thus the idea to use Tibet's waters for Northern China was born.

One of the possibilities was to divert waters from the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo, north of the McMahon Line, by building a mega structure. There are different versions of the project, but the Shuotian Canal is the most elaborated. It is the brainchild of an engineer, Guo Kai, whose life mission is to save China with Tibet's waters.

Guo not only worked closely with experts from the Chinese ministry of water resources and the academy of sciences, but he also made several on-the-spot investigations and surveys, before coming up with the details of his pharaonic scheme.

From the start the Chinese military have shown a lot of interest in Guo's Great Western Route scheme. In November 2005, the Great Western Route project got a boost with the publication of a book entitled Save China Through Water From Tibet, written by a Li Ling; the writer used Guo's theme and arguments.

In November 2006, Chinese Minister for Water Resources Wang Shucheng categorically stated that the proposal was 'unnecessary, unfeasible and unscientific.' He, however, admitted: 'There may be some retired officials that support the plan, but they are not the experts advising the government.' It was not a point blank denial as he admitted that the project existed. As we know, governments change, so do their advisors.

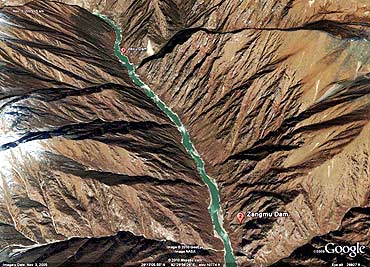

According to available information, the Chinese plan to build a series of five dams in the Shannan Prefecture (Lhoka) of Tibet at Zangmu, Gyatsa, Zhongda, Jiexu and Langzhen.

The Zangmu dam will be the first to be built. At an altitude of 3,260 metres, it is expected to generate 540 MW of electricity; its height will be 116 metres and length 390 metres, it will have a width of 19 metres wide at the top and 76 m at the bottom. The 26 turbines dam would cost 1.138 billion yuan.

The Government of India knew of the project for long, but seemed unwilling to forcefully question China.

During a recent question hour in the Rajya Sabha, External Affairs Minister S M Krishna informed the members that during his visit to China, Beijing had finally admitted to the existence of the dam. 'It is a fact that when we met in Beijing, the question of the power station did come up. The Chinese foreign minister assured me that there would be no water storage at the dam and it would not in any way impact on downstream areas,' Krishna said.

The latest developments and the Indian government's declaration raise several points:

At this stage it is difficult to link the string of five dams to the larger project of diverting the waters of the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra to northern China. The five dams, including the Zangmu dam, located upstream of the proposed diversion project are said to be a run-of-river project only.

The rationale to divert the waters of the Yarlung Tsangpo is more compelling as ever. Many believe it is only a question of time and one day China will have to go for it in order to survive.

For many months, the fact that China was building a dam in Zangmu was known and photographs were circulating on the Internet. Why did Delhi take up the matter with Beijing so shyly? It remains a mystery. Probably to not hurt Chinese 'sensitivities.'

The gorge of the Brahmaputra is a highly seismic zone. Most geologists agree that the area is prone to earthquakes. The South China Morning Post newspaper quoted Yang Yong, a Chinese geologist, saying that there 'is fresh evidence of violent geological movement. I cannot imagine a more dangerous spot to build dams.'

India and China have no water-sharing agreements. A meeting of experts from India and China took place between April 26 and 29, 2010 in Delhi to discuss the issue of sharing information on the Brahmaputra and the Sutlej. Hopefully the outcome will be made public. Indian and Chinese water experts have apparently inked an 'implementation plan' to share hydrological data on the Sutlej and Brahmaputra rivers.

Regarding the data of the Himalayan rivers, there is a major problem. The Indian babus are even more jealous of 'their' data than their Chinese counterparts. One wonders sometimes if these babus are really interested in 'national security'. How does it help to hide hard facts about the happenings on the Yarlung Tsangpo?

China has never consulted lower riparian States before undertaking dam constructions upstream, though it is considered as a trans-border water issue. As Indian scholar P Stobdan puts it: 'China has refused to join the Mekong River Commission, and has also not ratified the UN convention on Non-Navigable Use of International Watercourses (1997)'. This is an issue on which Delhi could insist when Indian officials meet their Chinese counterparts.

This lobby is very influential and advocates the diversion project. One should also not forget that several major Chinese banks have an interest in the mega-projects. Since the completion of the Three Gorges dam, these lobbies have not been able to undertake 'big' projects.

One of the main problems is that some Indian intellectuals (this word is not appropriate, because according to me, they lack intellect), believe that the Chinese 'are our friends' (if not brothers) and India cannot afford a conflict with the Middle Kingdom.

There was recently a talk at a reputed Indian think-tank in Delhi with the main Indian 'expert' arguing that even if the Brahmaputra is diverted, it will only be a mere 30 per cent of its waters which will be lost to India and Bangladesh, with no consequence for these countries. Frightful.

One can understand what is going to happen to India and Bangladesh (whether it is a diversion or simply a string of dams) when one looks at the fate of the Mekong. The 4,350 km river has its source on the Tibetan Plateau. It flows downstream to the Yunnan province of China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. During recent months, a severe draught has been experienced in the Yunnan province of China and the Indochinese peninsula.

The problem has been compounded by the fact that China has built several dams on the upper reaches of the Mekong river without consulting its neighbours. Environmental NGOs in the peninsula, however, blame China for 'drying' the Mekong and provoking the crisis. China, a dialogue partner of the commission, took the 'attack' seriously and sent a delegation led by Vice-Foreign Minister Song Tao to a two-day conference of the Mekong Commission in Thailand.

Liu Ning, the Chinese vice-minister of water resources argued that the dams and irrigation projects upstream have actually helped stave off some of the effects of drought. Facts speak otherwise. It is a fact that large dams have an influence on the ecology of the bioregion, whether it is admitted by the dam builders or not.

It is not that the Chinese are unable to bend and listen. In May 2009 Premier Wen Jiabao, himself an engineer by training, suspended the construction of a planned cascade of 13 dams on the Nu river (Salween in Burma). Already in 2004 Wen had blocked an earlier version of the cascade and asked for a serious review of the environmental impact to be carried out.

Wen's decision has been seen as the response to international and local pressure over the environmental effects of such a structure in an eco-sensitive region.

Last but not the least, there is a strong lobby in India which wants to build dams in Arunachal Pradesh. Ask any Arunachali minister, he will tell you: 'We are the richest Indian state, we will soon 'sell' 50,000 MW of electricity to India". The Assam Tribune recently reported: '(Arunachal Home Minister) Tako Dabi said international circles that did not want India to become energy efficient by tapping its natural resources had been behind such popular movements that were voicing opposition to the construction of mega dams like the one in Gerukamukh and the Dibang valley.'

This shows another aspect of the issue, more difficult to handle by a weak Centre.

One can only conclude that India is facing a complex and extremely serious problem; only by firm diplomacy and proper information of the public does India have a chance to force Beijing to change its plans, avoiding thus a regrettable fait accompli.