Photographs: Reuters

Our twisted minds may have justified the cruelty and inhumanity that Gujarat was witness to in 2002. A decade later, do we feel the need to reconsider our support for what we thought was 'right' back then, asks Urvish Kothari.

Here's the strange thing about facts -- some are so simple and self-evident that they elude us completely when they happen. Digesting them takes time -- two, three, seven, maybe even 10 years. By then, the passion and the anger have abated enough to allow a sense of composure to pervade our being.

This is what happened during the communal violence that gripped Gujarat in 2002.

Any mention of this shameful event is enough to raise the hackles of Chief Minister Narendra Modi's fanboys, even as their opponents ready a counterattack. But, after the passage of 10 long years, we cannot, and should not, first debate whether Modi was complicit in the crime.

As citizens, we have to put the first question to ourselves: Seen without the lens of party affiliation or religion, has whatever happened 10 years ago stirred feelings of unconditional embarrassment, regret and penitence in us?

...

Ten years later, how can we defend this madness?

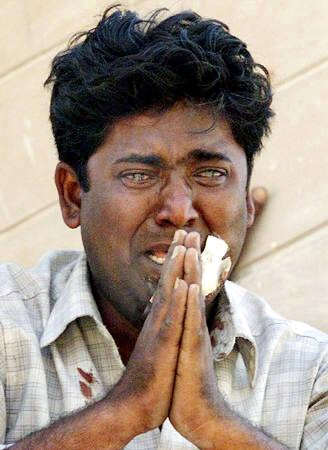

Image: The face of a Gujarat riot victim that went viral in the mediaPhotographs: Arko Datta/Reuters

There might have been reasons in our twisted minds to justify the cruelty and inhumanity that Gujarat was witness to. A decade later, do we feel the need to reconsider our mute or open support for what we thought was 'right' back then?

Unlike Amitabh Bachchan's unforgettable, angst-ridden dialogue from Deewar -- 'Jaao pehle us aadmi ka sign lekar aao... (First get them to sign...)' -- have we now developed a sense of calm that makes us look within and probe our own conscience for a change?

When a perfectly normal human being sets himself upon another just because he or she belongs to a faith not identical to his own... when he kills, burns, maims innocent people who could not even remotely be blamed for his blind rage.... Does the thought that we can't be doing this or even be seen defending this... this madness, come to our mind?

After all these years, do we find it within us to acknowledge that there is no way we can cling to this position any longer?

Or is our humanity satiated by an honest rickshaw driver who deposits a wallet full of currency that he chanced upon in his vehicle at the police station?

...

We are ordinary folk, not political foxes

Image: A file photo of the Godhra carnage sitePhotographs: Reuters

Supercop KPS Gill, who found himself in midst of the death and destruction that enveloped parts of Gujarat in 2002, mentioned years later that he had not seen any evidence of the 'Kalinga effect' in the people of Gujarat.

While that may certainly hold true for the state's powers-that-be, what about us citizens? Have we found any evidence of our awakening?

In the last 10 years, the realisation that they had indeed 'lost their heads then' does seem to have dawned on a small cross-section of troublemakers and a miniscule part of the police establishment. Journalist friends who know some of these worthies are witness to this happy turn of events.

The time has come for the rest -- who proudly refer to ourselves as 'We, The People of Gujarat' -- to speak the language of civility even if we, back then, openly supported the madness. We must do this without caring about what our trenchant critics would say about our volte face.

That we should never have suffered a momentary loss of reason is, of course, the ideal state of being. The fact is, we did. Now, the most honourable recourse available to us is to accept our faults and be vigilant about not repeating our mistakes. That will be our testimony to our humanity.

We are ordinary folk, not political foxes who trade in human lives. Why, then, must there be any shame in expressing fulsome regret for our appalling past?

...

Is there any way to forget that heinous crime?

Image: A man carries goods looted from a shop in riot-torn Ahmedabad while a policeman looks on.Photographs: Arko Datta/Reuters

Mention Gujarat 2002, and a whole army of people will instantly remind you of the Sikh massacre in Delhi that followed Indira Gandhi's assassination. Is there any way to forget that heinous crime? Especially when the victims are still awaiting justice?

The moment these two incidents of utter bestiality are simultaneously recalled, you have citizens neatly divided into two: On the one hand, we have party loyalists or those who wear ideological glasses or recycle the same old tired argument: 'The same level of carnage took place during the Congress's reign. The victims are still crying for justice. At that time, were you (read: you Congressi, you 'secular' farce of a man!) ashamed? No. Did you raise you voice? No. So why do we have to feel guilty for recalling what happened in Gujarat 2002? Why should we raise our voices?'

The Congress loyalists or, to use a quaint term, 'disciplined' foot soldiers (which is a short handle for those who have locked up their conscience and given away the key to the high command) will say: 'Let's talk about 2002. Our leaders have time and again expressed their apologies to the Sikh community. For consecutive terms, we have had a Sikh prime minister running our government. Your leaders still brazen it out without expressing the slightest remorse.'

The first of these arguments (Me? Ashamed? Huh!) was advanced with tedious regularity by a sizable majority during the political charged atmosphere that followed the violence in 2002.

...

Their very existence was dismissed!

Image: A protest against Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra ModiPhotographs: Reuters

Another argument that was widely propagated, and naively understood, was that there were only two sets of people: Congress leaning pseudo-secularists or the BJP chief minister's hardcore supporters.

Anyone who opposed the violence was immediately painted a dyed-in-the-wool Congressman, a pseudo-secularist, a rabid Hindu hater and a person who revels in double standards.

Anybody who was not an apologist for this brutality or who denounced the Gujarat-baiters -- and the statement, 'We need to be ashamed about the 2002 violence' -- immediately qualified as a 'true Gujarati.'

Between these two convenient and politically expedient extremes were a third set of individuals whose very existence was summarily dismissed. These people thought then, as they do now, that the crimes against the Sikhs in 1984 is a horrific stain the Congress can never wash away. It won't disappear by having a Sikh prime minister for two consecutive terms or by asking for forgiveness.

The only way to reduce this burden is to deliver justice to the victims and to punish the guilty.

...

Gujarat-hater, pseudo-secularist, Hindu-baiter, the epithets roll on...

Image: A riot-hit family from Ahmedabad outside their damaged housePhotographs: Kamal Kishore/ Reuters

In order to do so, the Congress party must co-operate with the judiciary in furthering the cause of the victims.

Even before the court announces its verdict, the Congress must pro-actively deal with the perpetrators of this violence within the framework of its organisation. Then, and only then, does an apology have any real meaning. Otherwise, it's akin to running with the hares and hunting with the hounds.

If the right-thinking citizens of Gujarat display such an awakening, it's admirable.

Any expectation from the Congress government in New Delhi is well-received, but the moment there is a similar expectation from the BJP government in Gujarat, all hell breaks loose: Gujarat-hater, pseudo-secularist, Hindu-baiter, the epithets roll on...

The massacre of the Sikhs in Delhi was criticised by citizens' rights organisations and public intellectuals from all walks of life. The relentless criticism of the then Congress government for its shamelessness and rigidity continues unabated to this day.

But when the same people and the same organisations critique what happened in Gujarat, they must face up to that idiotic riposte: 'Where were you when the Sikh massacre happened?'

...

Those who ask questions are not interested in answers

Image: A file photo of angry crowds on a rampage in Ahmedabad, killing Muslims, in reprisal for the Godhra incident.Photographs: Reuters

The trouble with those who monotonously parrot this question is that they are not interested in answers. They fling the question like a stone and run away!

What is conveniently forgotten is that, except for Rajiv Gandhi and some of his Congress leaders and goons, no one has defended the Sikh pogrom, leave alone justify it.

'We are not communal but we oppose double standards' is the other standard refrain used either to defend the violence that happened or level with the people who have spoken out against it. But these opponents of 'double standards' have never asked BJP leaders if they have done anything to help the victims after the Delhi pogrom.

If it is a question of 'double standards,' why did those who chose to keep quiet about the violence in Gujarat never ask a local BJP leader: 'Since you have been crying yourselves hoarse demanding justice for the victims of the Sikh riots, should you not be equally enthusiastic about demanding justice for the victims of the 2002 violence under your own administration? What exactly have you done to inspire confidence among the victims in their fight for justice?'

...

No party in this country truly wants justice

Image: Mourners surround the bodies of those killed when a mob burnt a train carrying Hindu devotees at Godhra.Photographs: Reuters

If a political party interested in squaring up its misdeeds limits itself to recounting its opponent's sins, that's acceptable. After all, there is not one party in this country which truly wants justice, not even the ones sitting in the opposition.

The 'fight for justice' is merely a tool with which to outmanoeuvre your opponent. None of the political parties have actually stood by the victims in a principled manner.

The contribution of the Congress in securing justice for the Sikh victims in Delhi is in direct proportion to the BJP's for the Muslim victims in Gujarat.

It's their fervent wish, therefore, that we as citizens neutralise their subsequent responsibilities for political crimes by taking adversarial positions favouring this party or that.

This is clearly a possibility when citizens, instead of speaking out on behalf of fellow citizens, indulge in arguments like 'You Congress, me BJP,' or defending the indefensible under the garb of party loyalty or a strange, mythical fear of the other.

...

The 'D' word!

Image: Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra ModiPhotographs: Reuters

The natural reaction one gets after 10 years is: 'How long do you want to remember this? Forget the past and move on.' (In the same breath, these worthies do not forget to recall the 28-year-old Sikh massacre, but that's par for the course.)

The fact is, be it Delhi's Sikhs or Gujarat's Muslims or, for that matter, victims from anywhere, they are in any case moving on without the need for such homilies. But 'moving on' cannot mean 'moving on without hope or expectation of justice.'

The tragedy, in this case, is that the present government in Gujarat is least interested in seeing that happen. Yet, its proud flag-bearers don't shy away from doling out such ill-timed advice.

Any talk of justice is muddled by dragging in the D word -- development.

There is certainly scope for an independent debate on Gujarat's progress. But, even if one assumes and accepts all the fancy theories on development, it still cannot be anyone's case that development can serve as a substitute for real justice. This is what We, the Citizens of the State, must understand.

...

The difference between reason and justification

Image: Poonam Ben weeps while searching for the body of her father-in-law at a morgue in a hospital in Ahmedabad.Photographs: Arko Datta/Reuters

As for the chief minister's role in the violence, without which no debate on this subject can culminate, there is one noticeable fact which exists sans all the theorising. This is the fact: it is, under his watch, that the Hindus in the Sabarmati Express and thereafter, during the riots, that the Muslims and others got mercilessly butchered.

For both these acts, the moral responsibility solely rests with the chief minister. Instead of mouthing platitudes -- such as 'It's natural for every action to have a reaction' and 'One does not want action, or a reaction' -- he could have acted as an elected leader should, and dealt with the rioters firmly. This would have sent a strong signal to the lumpen elements that no one was above the law.

The bureaucracy and the police administration are past masters at deciphering their 'chief's' unspoken orders. If a timely and unambiguous signal had been conveyed, the bureaucracy and the police would have stopped these crimes as they were happening, not as an exception, but as a rule.

A decade later, a sizable set of people still don't accept the difference between reason and justification.

If a biker who was not wearing his helmet dies in an accident, one can safely conclude that he died in an accident and he wasn't wearing a helmet. It can't stand to reason that he deserved to die because he wasn't wearing protective headgear and everyone who doesn't wear one also deserves to meet the same fate.

It's time for us, the vast majority, to think about Godhra, and the post-Godhra violence, and the nuanced difference between reason and justification from that lens.

The column was translated from Gujarati by Vistasp Hodiwala.

article