Xi's ascent to power and the quick consolidation of his leadership of the party with a shock anti-graft campaign securing the title of the “core leader” of the party bequeathed only to Mao has indeed forced his rivals in the party to submission and caught the attention of the world.

A decade ago when the powerful covert factions of China's ruling Communist Party chose Xi Jinping as a compromise candidate to lead the party in ending a bitter power struggle, few had an inkling that the suave and sedate "princeling" will cast himself on the mould of party founder Mao Zedong and bulldoze his way to become the leader for life.

At the 18th Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in November 2012 to choose a successor to then-President Hu Jintao, it was a toss between Xi, the then Vice President, and urbane and intellectual Vice Premier Li Keqiang.

Xi won the race following which Hu, who pitched for Li, made a quiet exit complying with the steadfastly adhered rule followed by all his predecessors handing over the reins to Xi, known as the “princeling” for being the son of the former influential Vice Premier of Mao era Xi Zhongxun.

Li, once Xi's rival, who became the number two ranked leader with the post of Premier in the ensuing months fell in line and endorsed Xi as the core leader, which made him the sole leader in terms of governing the party and the country.

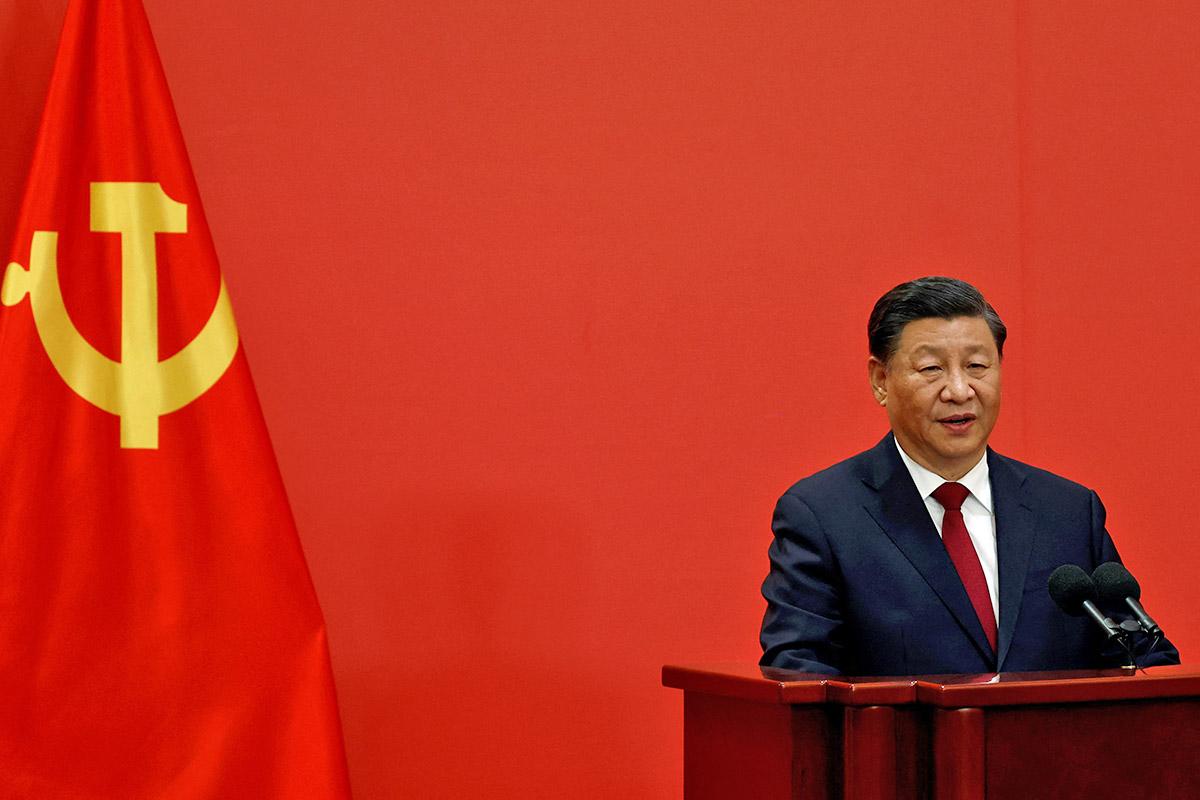

Ten years on at the 20th Congress in Beijing which concluded on Saturday, it was 69-year-old Xi's turn to hand over the reins to a successor as per the old norm but the CPC turned the page on its leadership transition to permit his continuation for a record third term and thereafter.

Xi's ascent to power and the quick consolidation of his leadership of the party with a shock anti-graft campaign securing the title of the “core leader” of the party bequeathed only to Mao has indeed forced his rivals in the party to submission and caught the attention of the world.

From day one after assuming power, Xi had launched a ruthless campaign against corruption, which besides striking a chord with people helped him systematically weed out political opponents, especially top Generals who posed a challenge to him.

"If there were only one lens through which to interpret Xi Jinping's remarkable rise over the past decade, then it would have to be his signature anti-corruption drive," said Wang Xiangwei, former editor-in-chief of the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post.

Since he came to power in late 2012, Xi and his supporters have deftly combined this ruthless effort with a relentless ideological campaign aimed at consolidating power by crushing political rivals and strengthening control over all levels of society, Wang wrote in his recent column in the Post.

"Xi has over the past decade investigated and disciplined nearly five million high-ranking and grass-roots officials, or tigers and flies," Wang said.

According to Xinhua, more than 400 officials at the ministerial level or above have been punished or investigated over the past nine years, including a former member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and two former vice chairmen of the Central Military Commission.

"Facts prove that if corruption is allowed to spread, it will eventually lead to the destruction of a party and the fall of a government," Xi said in a stern warning.

Unlike many Communist leaders, Xi who was born in 1953 saw the power in close quarters as his father Xi Zhongxun, a revolutionary hero, was appointed as minister of propaganda and education by Mao.

At a very early age, Xi and his family went through a painful period of suffering when his father was persecuted by Mao for his liberal views.

Xi spent his childhood close to Mao in Zhongnanhai, the official residential complex of the party leadership in Beijing, according to one account.

But at the same time Xi has seen his father lose all privileges after he fell foul with Mao and was exiled. At the age of 13, Xi had to leave school to go to the countryside during Mao's Cultural Revolution period, enduring hardships.

After repeated attempts, Xi succeeded in joining the CPC in 1974.

Years later, Xi was quoted as saying that attempts were made to prevent him from admitting to the CPC citing his father's alleged wrong acts.

"When a fault is committed, there is a verdict. But where is the one against my father? Who do you think I am? What have I done? Have I written or chanted counter-revolutionary slogans? I am a young man who wants to build a career. What is the problem with that?” Xi asked.

He was just 15 years old when he arrived in Liangjiahe in Shaanxi in 1969 as an "educated youth,", a recent write-up in the state-run Xinhua news agency said, highlighting his early life.

"It would take 38 years and multiple postings across various levels of the party's hierarchy until he would be elevated to the top job," the Xinhua write-up said.

From 1975 to 1979, Xi studied chemical engineering at Beijing's prestigious Tsinghua University.

Xi is married to celebrated Chinese folk singer Peng Liyuan. They have a daughter named Xi Mingze who studied Bachelor of Arts degree in psychology at Harvard and later returned to Beijing after Xi emerged as the top leader of the country.

Observers say an analysis of Xi's ten years in power, his systematic accumulation of power and contemptuous treatment of some of the top officials including military generals was born out of the suffering he and his family, especially his father had to endure.

"Xi Jinping, who grew up in the Beijing neighbourhoods inhabited by senior officials, did not seek wealth. It was the power that attracted," Francois Bougon wrote in his book “Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping”.

"According to the statements of the former acquaintance, gathered by the American Embassy (in Beijing) between 2007 and 2009, Xi was always “extraordinarily ambitious” and “never lost track of his goal” which was to reach the highest echelons," Bougon wrote.

During his decade in power, Xi's critics within the CPC have grown. One such critic was Cai Xia, a Professor at the Central Party School of the Chinese Communist Party from 1998 to 2012.

Xi was the principal of the prestigious ideological school of the party when he was the Vice President.

If the growing irritation among some party elites means that his bid will not go entirely uncontested, he will probably succeed, Cai said.

"But that success will bring more turbulence down the road,” Cai, who later turned bitter critic of Xi and managed to migrate to the US, wrote in her recent article in the Foreign Affairs magazine on Xi's continuation in power beyond his 10-year tenure.

"Emboldened by the unprecedented additional term, Xi will likely tighten his grip even further domestically and raise his ambitions internationally”, she wrote.

However, Xi's supporter argues that the party and the country need him.

Without a strong leadership core, the CPC would find it hard to unify the entire party's will or build solidarity and unity among people of all ethnic groups, Wang Junwei, a research fellow at the Institute of Party History and Literature of the CPC Central Committee, said.

It would not be able to achieve anything or carry out any of its "great struggles with many new historical features," he said.

For China and Chinese people, Xi's continuation in power heralds a new age with the trappings of the Mao era.

But for the world, Xi by now is a familiar figure, said a senior diplomat who preferred to be anonymous.

"Xi is China's new normal. Continuity in a way is good as the world has seen his ten-year rule. We know each other," he said.

But the zero-COVID policy could turn out to be a major challenge to the Chinese leader as he settles down for his prolonged rule, the unnamed diplomat said.

Scrapping the zero-COVID policy could turn out to be a moral, ethical and political dilemma for Xi as he blamed world leaders for neglecting their people while China cared for them.

Such policies could make or break any system, however strong it is because, for people, livelihoods are important just as their lives, he said.

© 2025

© 2025