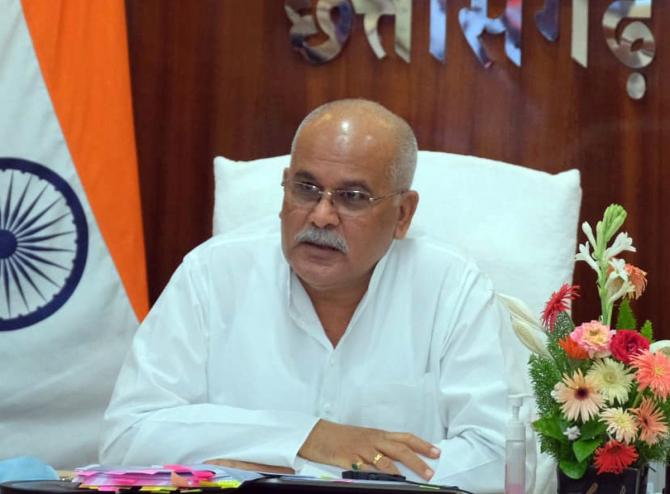

The Congress govt in Chhattisgarh is embroiled in a whole lot of controversies that enable the high command to continue acting as arbiter. Putting his father in jail is Baghel’s response to these complex power games, reports Aditi Phadnis.

Has a chief minister of any state ever sent his own father to judicial custody for making remarks that disrespect a community? It was a first. Chhattisgarh CM Bhupesh Baghel’s father, Nand Kumar Baghel, was sent to 15-day judicial custody by a court in Raipur for allegedly making derogatory remarks against the Brahmin community. He refused to seek bail.

In its complaint, the community alleged that Nand Kumar Baghel described the Brahmins as 'outsiders (foreigners) who should either reform or get ready to go to Volga from Ganga.' The police station in charge said, “The Brahmin community raised an objection to the statement made by Nand Kumar Baghel and complained to the police accusing him of creating tensions and spreading hatred in society.”

Bhupesh Baghel said about his father, “I respect my father as a son, but as a chief minister, none of his mistakes that will disturb public order can be ignored. No one is above the law in our government, even if he is the chief minister’s father.”

The senior Baghel, who is in his 80s, converted to Buddhism many years ago.

The cynical will dismiss this as a political drama. And it is true that the event came in handy at a time when the chief minister is facing political challenges from his own party.

But Bhupesh Baghel faces next to no challenges from the Opposition. The Bharatiya Janata Party has been comatose after the 2018 assembly elections when it could win only 15 of the 90 seats. Former chief minister Raman Singh has been drafted into party work as national vice president.

Andhra Pradesh leader and Congress import into the BJP, D Purandeswari, and four-time MLA from Bankipore in Bihar Nitin Nabin were designated as the Centre’s eyes and ears and to find out what was ailing the party. But it is work-in-progress.

But trust the Congress to create problems where none exists. Initially, after the Chhattisgarh elections were held in 2018, as part of Rahul Gandhi’s plan to introduce new Congress faces in the state, Tamradhwaj Sahu was chosen to become chief minister.

Baghel — and the other big Congress leader in the state, T S Singh Deo — had just returned from Delhi where they had each been given some sort of assurance of getting the top job when they landed in Raipur, only to find that Sahu’s supporters were letting off celebratory fireworks. Like the proverbial tortoise, Sahu had won the race. They returned to the airport and went back to Delhi where the man who made all contradictions disappear, Ahmed Patel, thrashed out a half and half arrangement for chief ministership. As part of that arrangement Sahu was made home minister.

Then came Covid-19, and it claimed Ahmed Patel. Now you had only Singh Deo’s word that he was given an assurance he would be CM for the second half of the term. When Baghel played the innocent and refused to budge, Singh Deo ratcheted up his protest a notch. And now Chhattisgarh has a leadership crisis on its hands, matching the one in the other two Congress-ruled states, Punjab and Rajasthan.

In between, reports of scams appeared: that the government was on the verge of deploying public resources to rescue a medical college in Durg that was in trouble. It was no coincidence that the college was owned by Baghel’s relatives.

Singh Deo, who is health and panchayati raj minister, keeps reminding the CM that promises in the Congress manifesto cannot be left unfulfilled. And the central government is after Baghel over the plot allotments in Durg in cases dating back to when Raman Singh was the chief minister.

As chief minister, Baghel is realistic and free of dogma. The rural economy is the centrepiece of his government’s economic policy.

The scheme of purchase of cow dung from farmers led to many theories about the government’s soft Hindutva. Godhan Nyay Yojana, or GNY, was launched in July last year. Since then, the government has disbursed Rs 64 crore to 1,40,000 cow owners for the dung collected from them. This is then transported to more than 3,500 government-run cowsheds where it is turned into fertiliser and other products.

And if Raman Singh’s triumph was the public distribution service (PDS) reform, Baghel’s promises to be procurement of grain: Chhattisgarh has set a record of procuring paddy under the minimum support price (MSP) scheme during the 2020-21 kharif marketing year. No Chhattisgarh farmer is protesting or demanding guaranteed MSP, secure in the knowledge that the state government will buy all his produce.

But with its genius for creating problems, the Congress government is embroiled in a whole lot of controversies that enable the high command to continue acting as arbiter. Putting his father in jail is Baghel’s response to these complex power games.