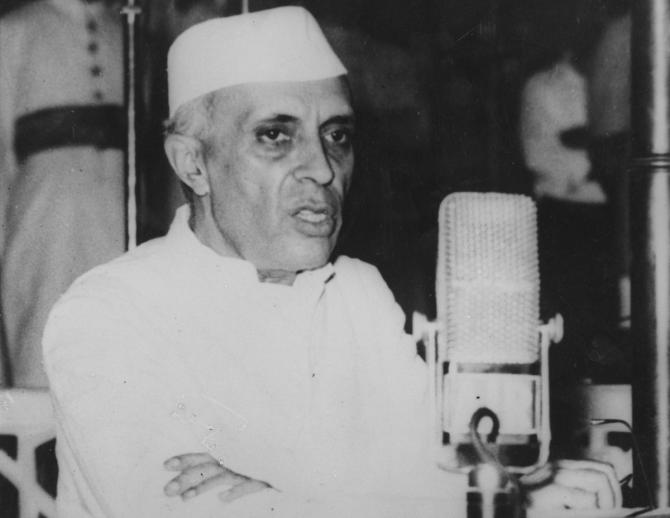

Hindu, Urdu, or something in between. That was the kernel of an argument between first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Hindi poet Harivansh Rai Bachchan over the translation of a presidential address from English to Hindi that was to be read by the then vice-president, Zakir Husain.

Nehru thought that Bachchan's translation of the then president Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan's speech was too complex and the Hindi poet was adamant it was not, says the book Nehru's First Recruits by journalist Kallol Bhattacherjee. Both were unwilling to relent.

Recounting what had happened, the book says Nehru lost his cool with Bachchan, whom he had recruited as an officer on special duty for Hindi at the ministry of external affairs.

Bachchan, who authored the landmark Madhushala, joined the Indian Foreign Service in 1955 on a monthly salary of Rs 1,000, a good Rs 250 hike from his previous job as a producer in the All India Radio , according to the book.

The major part of his responsibility in the MEA included translating speeches of the president and the vice president -- the commonly used Hindi name 'Videsh Mantralaya' for 'external affairs ministry' was, in fact, coined by Bachchan.

The argument with Nehru happened when Bachchan translated the president's speech in English into Hindi, which in accordance with regular practice was to be delivered by the vice president.

"Do you realise who is to read this speech? Dr Zakir Husain— and he won't even be able to pronounce some of the words you have used," the book quotes Nehru as saying.

"Panditji, language cannot be changed to suit the convenience of some individual's pronunciation; why don't you have the speech translated into Urdu?" Bachchan had replied.

The clash of egos between two men, held in high esteem in their respective domains of governance and literature, led to a full blown verbal spat and Nehru ran out of patience.

The book quotes in detail the conversation between the two luminaries.

"There is enough trouble in this country. Even if we get it translated into Urdu, we'd have to call it Hindi -- and what's the difference between the two, anyway?" Nehru said.

According to the book, Bachchan, in his endeavour, had forgotten the realities of India and was about to get the vice president of India into a difficult situation.

"The vice president stumbling over difficult Hindi words while reading a speech in the Parliament would not have gone down well before the media and the critics of the Nehru government."

"And Nehru was also right to some extent in his own way because the speech could not possibly have been translated into Urdu, as the Indian Constitution only allowed for the use of Hindi speeches in such sessions, and a Hindi speech with many Urdu words, therefore, would have to be called a ‘speech in Hindi' and not an Urdu speech," the book explains.

Ultimately, Nehru regained his composure and convinced Bachchan to produce a text that Zakir Husain would not find difficult to read. And Bachchan duly obliged.

Husain, who held the office of vice president from 1962-67, under the presidency of Radhakrishnan, later succeeded him as the third president of India.

Nehru knew Bachchan, both hailing from Allahabad, way before he recruited him in the IFS, says the book.

In fact, he had helped Bachchan receive a scholarship after he got admission in Cambridge and Oxford in the early 1950s. Bachchan had faced a series of rejections from then education secretary Humayun Kabir and education minister Maulana Azad.

"Bachchan sought time from PM Nehru and met him in the Parliament. Nehru remembered Bachchan, the poet, and gave a patient hearing. On learning that he had failed in securing a scholarship, Nehru called his personal secretary in Parliament, BN Kaul, and asked him to arrange a scholarship of Rs 8,000 for Harivansh Rai Bachchan," informed the book.

Nehru's First Recruits, published by Harper Collins India, uses stories and experiences of India's earliest diplomats to present the foundational history of the country's diplomatic corps and the beginning of the country's engagement in global affairs.

© 2025

© 2025