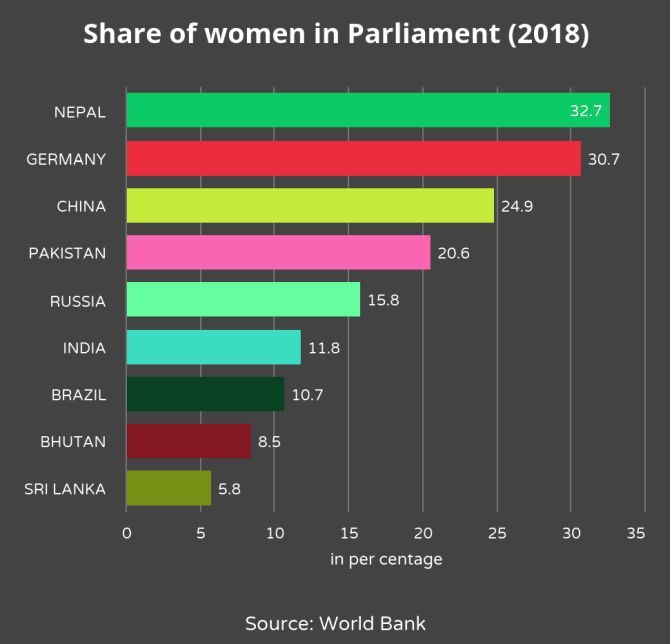

With just 11.8 per cent, the nation lags behind its neighbours and peers when it comes to women’s representation in national legislatures, report Sachin P Mampatta and Abhishek Waghmare.

Nearly a century has passed since the first time an Indian woman voted to elect her representative in British India: it was in Madras in 1920. With universal adult suffrage in 1952 and granting 33 per cent reservation to women in rural local bodies in 1993, it has come a long way over the last century.

However today, India lags behind its neighbours and peers when it comes to women’s representation in national legislatures, an analysis of global data shows.

The proportion of elected women representatives in the Lok Sabha touched its peak at nearly 12 per cent in 2014. At 24.9 per cent, China has more than twice the representation. While Nepal elected thrice as much women to the national legislature than India, Pakistan’s situation is nearly as that of China, with twice as much female representatives.

Evidence shows that quotas are, if not the only, a surely proven way of ensuring political gender balance. Countries without quotas had lower representation than those that mandated at least 30 per cent women’s representation.

Going further, those that sought parity -- half of the seats for women -- had the best representation, according to a report entitled ‘Women in parliament in 2018,’ from the Inter-Parliamentary Union, a global organisation of national parliaments.

In countries without reservations for women, the proportion of women representatives was 18.6 per cent in the lower house (or in the case the country doesn’t have two legislative chambers) and 16.2 per cent in the upper house.

In countries with reservation, it rises to 27.7 per cent and 36.1 per cent, respectively. Where parity is mandated, it improves further to 29.3 per cent and 47.1 per cent respectively.

“There are marked differences in the average share of women elected in legislatures without quotas, compared to those that require at least 30 per cent women. These differences are even greater when measures stipulate gender parity,” the IPU report noted.

Praveen Rai, a political scientist at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies said that reservation of seats for women is the only way for correcting gender imbalance. “The main reason for their exclusion is systemic failure and patriarchal fault lines in existing party system. Parties failed in including women in their ranks and file on stereotype belief that politics is the domain of men,” he said.

He added that the opening of party gates to men with criminal records further deterred women from politics.

Regional political parties such as Trinamool Congress and Biju Janata Dal have committed to fielding women in a third of seats they contest in 2019 general elections. The Congress has promised to bring back the women’s reservation bill, which was scuttled in 2010.

Global comparison shows yet another interesting trend. Though women’s share in Parliament improved from 8 per cent in the 12th Lok Sabha (1996-1998) to 11-12 per cent in 2014-2019, the gap with RoW is at its widest in at least 20 years, shows data from the World Bank.

Global agencies have pointed out underlying socio-economic conditions, which then translate into imbalance in political representation on the surface.

In 29 of 150 countries analysed by the World Economic Forum in its Gender Gap Report (2018), women spend twice as much time on unpaid work, housework, household care, than men. But in Japan, Korea and India, the time spent on house work is five times that of men.

At the deeper level, India is among the only four countries, where sex ratio at birth is below 910, the WEF paper shows. For 75 per cent of the countries, it is at the natural biological rate where 944 females are born per 1,000 males.

Data from the last few general elections do not imbibe hope. Though women candidates nearly doubled over the course of two general elections, male candidates have grown slower, yet by nearly 50 per cent in the period (2004-2014).

As a result, the proportion of women candidates has remained in single digits, between 6 and 9 per cent across the last three general elections, data maintained by Association for Democratic Reforms, a public advocacy, shows.

It also showed that richer women have disproportionate representation, narrowing the available arena for representation of women from more disadvantaged sections.

© 2025

© 2025