Investigative journalist and author Harinder Baweja, who was among the speakers from India participating in the International Kashmir Conference in Washington, has stated that when it comes to the issue of Kashmir it was hard to be objective.

Investigative journalist and author Harinder Baweja, who was among the speakers from India participating in the International Kashmir Conference in Washington, has stated that when it comes to the issue of Kashmir it was hard to be objective.

Baweja, editor (news) of Tehelka.com, who noted that she has been "in and out of Kashmir at least a 100 times in the last 20 years," since her first visit in 1989, said: "I keep going back to Kashmir because there's something about Kashmir problem -- and this is a huge admission to make -- that sometimes makes me lose my objectivity as a journalist."

"The reason for that is that Kashmir is a humungous human tragedy," she added.

Baweja argued that the main reason that a resolution of this problem had been elusive was because of "India's mind-set."

"Yes, India is a victim of terrorism, yes, there are foreign mercenaries who come into Kashmir, (and) the government of India loves to point a finger in Pakistan's direction, loves to point a finger at the ISI, but as journalists we know the ground realities. And, if there is a problem in Kashmir, it is because it was created by subsequent governments, both in Srinagar and Delhi, and if the ISI is meddling in Kashmir, it's because India muddied the water in the first place."

Baweja pilloried New Delhi for what she described as its sustained "policy of containment in Kashmir, and the problem lies in this policy because it then does not look at the problem in all of its dimensions, but looks at it largely as a law and order problem."

"India's constant policy is that Kashmir is an integral part of India and therefore an internal issue, and this, in my view is really the main problem," she said. "Since its inception, the government of India has been paranoid at the thought of international intervention, interference or even interest in the Kashmir issue."

Baweja alleged, "India has taken recourse to the Shimla Agreement and emphasised bilateralism because India has never really been sure that the world by and large accepted the legitimacy of its control over Kashmir."

"But forget about the international community, the people of Kashmir do not accept India's legitimacy over Jammu and Kashmir, but government of India is still caught in the containment policy. They believe that any concession given to Kashmir, will in turn open the floodgates for demand in other states."

Thus, Baweja argued: "New Delhi's stand therefore, has been that it will look at the Kashmir case, not in isolation but in conjunction with national policy concerning the devolution of more powers to all states."

She said, "India sticks to its policy of containment because it feels that it can solve Kashmir just as it handled Punjab militarily and that is a huge mistake to make because Kashmir is not Punjab."

"Punjab was never a territorial dispute, not did it have the international ramifications of the Kashmir issue and greater autonomy or self-rule does not and will not undermine India's secular credentials, but perhaps strengthen them."

Baweja asserted, "The deep and widespread alienation felt by the Kashmiris is not something that can be taken care of through the law and order machinery. Go to Kashmir, and it is difficult to get from the airport to the hotel room without crossing at least 20 bunkers. In fact, Srinagar is also known as bunker city."

She said, "Kashmir is not a piece of real-estate and should not be considered as prime property and that is often the approach taken by the government sitting in New Delhi."

"It is imperative for any government, no matter which political party it comes from, to look at Kashmir as a human problem and not as a legal property issue."

Baweja claimed that while the "hard-core foreign militants outnumber the Kashmiri militants, the reason why the common Kashmiris, the common masses, still do not view India as democratic is because they continue to see the government as being their oppressors and their tormentors."

She said, "The only time I have seen the Kashmiris react positively to any signal from New Delhi was when there was a call for a ceasefire by the Hizbul Mujaheddin in June 1999 and then New Delhi sent a team of officials to try and talk to the Hizbul Mujaheddin, but the talks of course, faltered and failed very quickly."

Baweja reiterated that "alienation is a core problem, and I have not see a change in 20 years that I have been going to Kashmir. I've not found the Kashmiris move even an inch closer to India or to Delhi. It is difficult to find a Kashmir family that has not lost a loved one to the military."

"An entire generation of children born after 1989 have grown up with the gun and the psychological effects on this are great both for children and for parents," she said.

Dr Angana Chatterji, a professor of anthropology at the California Institute of Integral Studies who circulated a detailed paper titled Militarization with Impunity: A Brief on Rape and Murder in Shopian, Kashmir that she had authored with Gautam Navlakha of the Economic and Political Weekly, New Delhi, placed the onus firmly on the Indian government to ensure that as Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had pledge, there would be "zero tolerance" for human rights abuses in Jammu and Kashmir.

She argued, "A will to peace in Kashmir requires an attested commitment to justice, palpably absent in the exchange undertaken by the government of India and its attendant institutions with Kashmir civil society."

Chatterji said, "The premise and structure of impunity connected to militarisation, and corresponding human rights abuses, bear witness to the absence of accountability inherent to the dominion of Kashmir by the Indian state, and a refusal to take seriously the imperative of addressing these issues as the only way forward to a just peace."

She called for demilitarisation in the valley and emphasized that it must not just be a "token withdrawal" that should also be couple with the release of political prisoners and the repeal of laws that "have enabled the security forces in Kashmir to act with impunity."

Navlakha, speaking at the session titled 'When Peaceful Protests Fail, What Next?' warned that if the aspirations of the Kashmiris continued to be ignored, the armed struggle could very well start again and predicted that it would have dire "repercussions for all of South Asia."

He recalled the "tens of thousands" who took to the streets last summer in protest at the grant of land around the Amarnath Shrine to the Shrine Board and said this mass reaction "that shook the Indian state" could be a precursor to further protests to come.

Dr Karen Parker, chairperson of the Association of Humanitarian Lawyers, acknowledged that during the two days of discussion at the conference, "we have scratched the surface but we have also dug deeply. We are at a junction right now with a new President (in the United States) and a possible new agenda."

She said, "If there is any time for us to push the issue harder, it is now. We will not get a more favourable time than now."

Parker warned, "If we lose this opportunity, we might have to wait a really long time."

Meanwhile, Dr Ghulam Nabi Fai, executive director of the Kashmiri American Council, said in the final analysis "nothing new" might have been achieved by the conference, but argued that it had been important to enhance understanding of the issue.

Furthermore, he noted that amongst the participants, there had been "no disagreement that the rights of the people of Kashmir, irrespective of their religion or regions, must be respected."

"This principle, was unanimously presented and conveyed and adopted by everybody," he said.

Fai also said that while it was a "healthy sign," that India and Pakistan had decided to re-engage and resume the dialogue "we really want them to talk sense."

Earlier, Fai, had argued that "the passivity, the inaction and silence, is not an option. Passivity is not an option because when we talk about Kashmir, we talk about an issue that concerns not only 15 million people of Kashmir, but because that issue also touches the lives and the future of more than 1.2 billion people of South Asia that is home to one-fifth of the total human race."

He said, "The time has come that President Barack Obama needs to listen to what candidate Barack Obama said on October 23, 2008 -- and that is an appointment of a special envoy on Kashmir will go a long way to hasten the process of peace and reconciliation not only in Kashmir but in the whole region of South Asia."

British author Victoria Schofield, who is also a regular contributor to BBC, who has also visited Kashmir several times, warned, "While the dispute continues, there's every opportunity for people to take advantage of the unstable Indo-Pakistani relationship for their own objectives."

"We saw what happened with Mumbai in November last year," she said, and added, "The attacks had nothing to do with the political grievances of the Kashmiris. Indeed, the political parties and members of the All Parties Hurriyat Conference condemned the attacks. But because of the unstable relationship between India and Pakistan over Kashmir, it was somehow viewed that the terrorist attackers were fighting for the Kashmiri cause."

Schofield said, "Like it or not, Kashmir is an international issue. For us in Britain and people living in the United States, the issue exists both as a political and human issue."

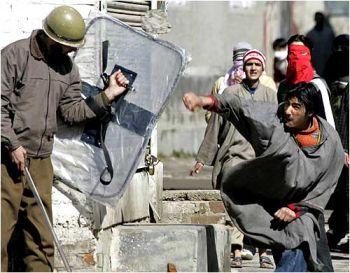

Image: A Kashmiri protester throws a rock towards a Jammu & Kashmir cop during a protest

Text: Aziz Haniffa in Washington, DC | Photograph: Danish Ismail/Reuters

© 2025

© 2025