Israel's Arab minority is not happy. In a recently published manifesto, their leaders have rejected the idea of the country as a Jewish state. What they want is a partnership -- to govern Israel as well as ensure that Arab citizens get equal treatment and more control.

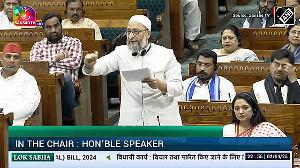

According to a report in The Los Angeles Times, Arab leaders have declared that Israel's 1.4 million Arab citizens are an indigenous group with collective rights, not just individual ones. They argue that Arabs are entitled to share power in a bi-national state and block policies that allegedly discriminate against them. Another report by The Wall Street Journal mentions the growing mistrust between Israel's Jews and Arab citizens that came into sharper focus last weekend after an Israeli-Arab cleric called for a new 'intifada', or uprising, in response to construction work near one of the country's holy sites.

Arab citizens have long protested the disproportionate share of budget resources and land that is skewed towards their Jewish neighbours. They feel alienated by the Star of David on Israel's flag. Their national anthem -- that speaks of Jewish yearning for a return to the land of Zion -- bothers them. And, while there have been small pockets of dissent among Arab intellectuals, this is the first major demand by the mainstream.

The manifesto, 'The Future Vision of the Palestinian Arabs in Israel', was drafted in December 2006 by 40 academics and activists and endorsed by an unprecedented range of community leaders. It was widely circulated only in January and, naturally, set off alarms. Jewish leaders seized on it as evidence of a growing militancy by the minority. The fact that Arabs sympathised with Hezbollah guerrillas fighting Israel in the 2006 war in Lebanon didn't help.

As the LA Times report points out, critics argue that adoption of the manifesto's proposal to redefine Israel would undermine Jewish support for a separate Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Some have denounced the manifesto as the work of an internal enemy that threatens Israel's identity.

However, the sponsors of the document say that most of the criticism misses the point. They say the manifesto is not an ultimatum. Rather, it is an effort to register Jewish discrimination against Arabs and encourage debate about how Israel's two largest communities should live together. All they want to do, they say, is change the Arabs' situation as second-class citizens, through dialogue.

Nearly half of Israel's Arabs live below the poverty line. When it comes to public education, the state invests almost twice as much per Jewish pupil as its Arab counterpart. The rates of unemployment and infant mortality for Arabs are twice the national average. They are exempt from military service, and do not qualify for thousands of higher-paying jobs reserved for veterans. They also comprise a mere 10 per cent of Israel's university undergraduates. There is also limited Arab representation in central government, considering they hold just seven of 120 seats in parliament.

Still, Arab leaders acknowledge that recent Israeli governments have recognised a need to tackle these inequalities. The manifesto urges Israel to adopt a 'consensual democracy' like that of Belgium, which reconciles its Flemish and French-speaking communities through power sharing and local autonomy. If accepted by Israel, this system would give Arab communities control over decisions about education and religious affairs.

Needless to say, the proposals have elicited debate among Jews over how to accommodate this impatient minority. They fear the disruption of an already fragile relationship, and recognise that the solution lies in dialogue. For now, possibilities of coexistence still exist.

© 2025

© 2025