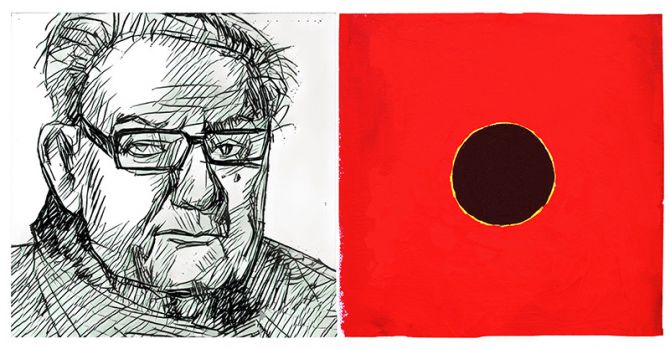

'Raza exemplified a sense of warmth and a connectedness to his roots and to Indian earth.'

Hugo Weihe, CEO, Saffronart and former international director of Asian Art at Christie's, believes that S H Raza, the legendary painter who passed into the ages last month, is one of India' art heroes, someone who helped Indian modernism find a wider audience.

In the concluding part his fascinating interview with Rediff.com's Vaihayasi Pande Daniel, Weihe discusses Raza, his art and the late painter's philosophical inclinations.

You said in an interview that Raza is one of the most prominent modernists of India. But is he really a modernist?

His Bindu series symbolised so much culture. Modernism would be just a title for a huge amount of depth?

You are right. How do we define modernism? Geeta Kapur wrote a very important book -- When was Modernism in Indian Art? -- precisely to ask this question. It is not an exact definition. It really means something that has already become something classic.

We are already looking back in Western art. We look at the period of the early 20th century Picasso, and others, as defining modernism. And there is post-war art, after that, right.

For India, it is not post-war, it is post-Independence and that becomes the golden era now of modernism. But modernism starts with (Rabindranath) Tagore, it starts with (Raja) Ravi Varma.

Again it is a progression.

Yes. Raza looked at Indian culture and history and symbolism, as every artist is always conscious of everything. So, the Bindu refers to far deeper philosophical principles, which are thousands of years old.

Actually, the book that Ajit Mookerjee published in 1966 on tantra (Tantra Art) was a key moment.

That was also what released the thinking for Raza and a whole hippy generation in the West was drawn to India by this.

Anyway, modernism is something we look back now to the beginnings in the early 50s, and that's 50 years ago or more -- it is now modern as opposed to contemporary.

You told The Hindustan Times some years ago: 'Having studied the art of several cultures, especially of Asia, I find Indian art to be extremely human and emotionally expressive; it is easy to relate to. I appreciate the deep roots in philosophy, parallel concepts of iconic and aniconic representation.'

Would you say that about Raza too?

100 percent! What I meant with the iconic and aniconic (not portrayed in a form or image), which also relates to Raza -- Shiva as an anthropomorphic form and as a Shivaling. That is a fascinating concept really, that they co-exist.

With Raza too it is the tantric imagery versus the realist, which is also still behind it. But these things co-exist. That is an extraordinary thing that Indian art does. It doesn't exist quite the same way really in any other art form.

And then, yes, the deep humanity is there and Raza exemplified that.

In what way?

As a human being! In his sense of warmth, and his sense a connectedness to his roots and to Indian earth.

One of his key topics is La Terre, the earth, which is one of the (important) works. You will see the title re-appear, many times. He is fascinated by the roots; that's in a sense in my quote.

Do you own some Razas? When you look at one of his Bindu series, for instance, what do you feel?

He actually gave me, very kindly, a drawing (laughs) and dedicated it.

During that visit to Gorbio?

Yes. That's for me a much cherished memory.

I look at a work of art on an emotional level, instinctive level. But I also understand/appreciate the person behind it, the master behind it, and I appreciate the journey that he took to get there.

So, a painting is almost just a moment in time too, but it reflects a whole journey. I view it, always, as something much bigger and holistically.

Also for you especially that one, is a memory?

Absolutely...

How very saleable was his work in the international context? At the Mumbai Gateway Dialogue conference in June you spoke about how the work of an artist grows in esteem. What led to the growth in esteem towards Raza's work?

International recognition and validation is important. That happens through exhibitions, through the support of galleries, through the publication of books, notably the first catalogue resume of any Indian artist. That has appeared.

The Vadehra Art Gallery (with help from) and (Ann Macklin of) Grosvenor (Gallery) published the first volume of his works from the 50s. Raza (from) the very beginning had a system of recording numbers, serial numbers so to speak, for his paintings. They had those records and were able to establish which paintings that matches up with.

A catalogue resume means you are recording every single work an artist did in his lifetime. That's the first step, and it's the first time it's happened for an Indian artist; it was happening when he was still alive. So, that is a beautiful thing...

We need to look at the recognition now, over time. There is a legacy now. A complete body of work. We look to assess it and assess it further. It will lead, obviously, to more exhibitions. International recognition will grow.

It is not a straightforward answer to say the prices will immediately go up -- that's never quite black and white. Sometimes yes. Certainly over time. With (M F) Husain it didn't happen straightaway.

What happens really, I find, is a general assessment of the entire body of work, which is now finite. Then you see, with greater clarity, the sort of milestones as I described before, the highlights, and that whole journey as a complete journey. So it is a moment of assessment now.

Let's say you appreciate a certain writer. When you look at how he wrote when he was younger, you realize there are certain emotions associated with that period. Then, of course, the craft gets better and better as the writer gets older.

If you apply that to art, the Bindu phase was what happened later to Raza as a more sophisticated, experienced artist.

When you look at it from an emotional view point, how does his work earlier to the Bindu phase measure up?

That a very good question. For me it is the journey of the artist.

There is a raw talent in Raza right from the very beginning, which (the legendary photographer) Henri Cartier Bresson spotted in this late teenager, barely 20 years old. 'I can see you are going to be a great artist. You should come to France. That will be a big step for you.'

If you look at Picasso, we look at his Blue Phase, where he is barely 20 years old, as maybe one of his greatest achievements -- think about it.

Your argument is correct, you could argue well it is not a fully-formed or fully-polished artist yet, but the funny thing is over time (laughs) we see that actually those maybe (were Raza's) biggest steps and there you see what's going to happen later.

It doesn't mean that the latest work is the best one by your definition. Probably it isn't. Maybe that early one is. Maybe that one in the middle. The point is the whole view is what matters.

Raza had a historical role in the Indian art community, as one of the founders of that early art chapter, Bombay Progressive Artists Group and more. Do you feel that added to his legend?

I think it is an incredibly important thing that happened. That there were like-mind artists -- (F N) Souza, Husain, Raza, (K H) Ara -- at the core of it and they felt: 'We need to go in a different direction.'

They all chose a different path. Raza (after earning a degree at JJ School of Art, Mumbai), he went to France. Souza went to London. Husain stayed home. And Ara too. What joined them together is (that they thought and discussed then) the new way forward and each of them plays an important role.

Raza's role was a very pre-eminent one. He defined a new artistic modernism for India. And it is a great achievement.

And you said M F Husain stayed home. Did Husain lose out by staying at home?

Not at all...

Or maybe Raza lost out by not staying home?

Yes... fair enough. Husain said the power of Indian culture lies in the villages. 'I must stay here. I must travel around and must see all that.' That was his source of energy and artistic inspiration. Later, he also travelled the world.

For Raza it was something else. It was absorbing all the art, he could, of the world, in the museums of Paris and then taking in that beautiful light of southern France, that in some ways matches up with the light of India and the colours, but in an interesting contrast.

He was very susceptible to exactly that sort of equilibrium. Or that tension in between. That was his artistic inspiration. There is no one way, right. Both of them benefitted, in their own way, from their sources of inspiration.

When you went to meet him, or in the earlier meetings that you had with him, what was something you always wanted to ask him about his work or his oeuvre?

Actually I didn't ask him any questions specifically because I felt I understood, just sitting there with him.

© 2025

© 2025