'Both empires had profound influences on modern India.'

'But neither can India's history be reduced to the actions of imperial rulers.'

'We need to think about India's history beyond India's current borders.'

Harvard historian Sunil Amrith, 38, was utterly surprised and shocked to hear that he had won the prestigious MacArthur 'Genius' Grant.

He felt a sense of detachment after the phone call ended -- almost as if it were happening to someone else. He had no inkling that he had been nominated, and had never dreamed that he would win something like this.

The news coincided with another tiding of great joy -- the birth of his daughter five days ago.

The MacArthur Fellowship is a five-year grant of $625,000 awarded to individuals who show exceptional creativity in their work and the prospect for still more in the future.

Individuals cannot apply for this award; they must be nominated.

Kenya-born, Singapore-raised Amrith left the University of London where he taught history for nine years for Harvard in 2015. He is the Mehra Family Professor of South Asian Studies and Professor of History, and a Director of the Joint Centre for History and Economics at Harvard, one of the most prestigious universities in the world.

His research has focused on migration in South and Southeast Asia and its role in shaping present-day social and cultural dynamics.

Among his works are Crossing the Bay of Bengal: The Furies of Nature and the Fortunes of Migrants, Migration and Diaspora in Modern Asia and Decolonizing International Health: South and Southeast Asia, 1930-1965.

He is currently on a sabbatical writing Unruly Waters about how water has shaped modern India. The book will be published in 2019.

A lover of jazz music, he is also a busy parent -- along with his British barrister wife who is a lecturer at the Harvard Law School -- to a four-year-old son and 12-day-old baby girl.

The MacArthur 'Genius' explained to Rediff.com's Archana Masih in an e-mail interview how we should explore the past in all its complexities and why he is wary of the term 'genius'.

Part I of a must read interview!

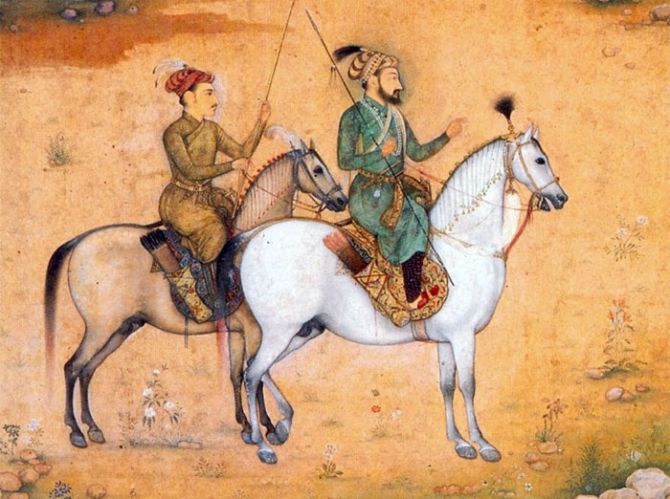

Does the Taj Mahal stand out as a symbol of invaders and plunderers? Is it foreign or Indian?

What is the best way to deal with a historical past that a section of people are uncomfortable about?

The Taj Mahal is a work of enduring architectural beauty that every Indian can consider part of their cultural inheritance, in just the same way as Indians can appreciate and embrace the beauty of the temples or gurdwaras or churches that shape our landscapes -- or even, for that matter, the British colonial architecture of Mumbai or Chennai or New Delhi -- regardless of their faith or political inclinations.

Many of the world's great monuments were built by rulers whose actions and ethics we no longer condone. Many great monuments were built by forced labour.

As Walter Benjamin once wrote, 'Every monument of civilisation is also a monument of barbarism.' We should bear that in mind.

I think we can have the cultural maturity to live with contradiction: We can appreciate architecture and art aesthetically while still delving into the conditions of their production.

We can give new meaning to the monuments that we live amongst if we treat them as part of a living, evolving culture, rather than as frozen in time and fixed in significance.

One of the things that has always impressed me about Indonesia is the level of comfort that country has with its diverse past.

Indonesia is the world's largest Muslim country, and quite happily celebrates as part of its heritage a Buddhist site like Borobodur, or the wayang kulit shadow puppet theatre which reinterprets the Ramayana.

There is no contradiction there, and I think that shows an inspiring level of cultural self-confidence.

Of course, the forces of intolerance are on the rise in Indonesia, too, so that too may change.

I do think the quest for cultural purity is a dead end. Are we going to abolish potatoes and chili from our cuisine as symbols of Portuguese conquest?

Serious history is not about searching for heroes and villains, it is about trying to understand the choices and the dilemmas facing people in the past -- choices which may or may not be familiar to us today.

As a student, teacher and lover of history -- what are your thoughts on the manner in which history is being contested in India?

The Mughals are receding from text books.

Icons of the right are making their way into political culture and iconography -- how do you see this churn, this revision of history affecting Indian history?

I think our main responsibility as scholars and students of history is to explore the past in all of its complexity.

We can no more do away with the Mughals in our textbooks than we can do away with the British. Both empires had a profound influences on modern India.

But neither can India's history be reduced to the actions of imperial rulers.

There are so many dimensions to history that we need to attend to: We need more space for local and regional histories; we need to delve into the histories of particular communities; we need to emphasise gender history and environmental history; we need to think about India's history beyond India's modern borders.

The very division of Indian history into successive imperial epochs can divert us from other sorts of historical change that followed different rhythms.

Serious history is not about searching for heroes and villains, it is about trying to understand the choices and the dilemmas facing people in the past -- choices which may or may not be familiar to us today.

We need to recognise the ways in which institutions and policies forged at particular moments in the past may well continue to shape the world we live in.

Moral judgement is, of course, an important part of the discipline of History -- it is certainly our responsibility to assess the consequences of past political systems, especially when these consequences may still be the source of inequality in the present day.

But this is not the same as retrospectively applying our contemporary moral preoccupations and standards to a past in which they may have had no meaning.

I am all for recovering forgotten voices and revisiting historical figures, as long as this is done in a rigorous way that adheres to standards of evidence.

The danger lies in cherry-picking or even mythologising historical examples to legitimise a contemporary political agenda, which is, I fear, what is being done by those who wish to emphasise only the 'Hindu' dimensions of India's past.

The path to a better understanding of our contested past must lie in maintaining the autonomy of institutions like the ICHR (Indian Council of Historical Research) or the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library.

In order to debate the past, we need to preserve its traces, and so we need to support and respect our archives and manuscript libraries; and we need to respect the integrity of the scholarship going on in India’s universities.

As a student, teacher, and lover of history, my main source of optimism comes from the fact that India has one of the greatest concentrations of outstanding historians anywhere in the world.

Any country would be lucky to count among its historians such brilliant minds as Seema Alavi and Srinath Raghavan, Radhika Singha and A R Venkatachalapathy -- to name just a very few.

What does being a MacArthur Fellow mean for an individual? What does this badge of honour, this stamp of genius, help in shaping individual work and her/his future?

It's a huge honour, of course. The MacArthur Fellowships are given to individuals, yet my work is always part of a collective endeavour.

I hope that my award will also bring more attention to the work that so many others are doing on Asian history, on migration, on environmental history.

In terms of shaping my own work in the future, clearly this is a huge boost of confidence; it brings me very generous resources to put towards my research; it will, I hope, open up new collaborations and relationships by bringing my work to a broader audience.

But the fundamentals of my working life won't change -- I shall continue to do research, and write, and teach.

I'm very wary of the term 'genius' -- and indeed the MacArthur Foundation themselves don't use it! -- it suggests a special innate ability that I really don't have.

To put it another way, genius comes in countless forms, and most often goes unrecognised.

How do you intend to use the $625,000 over the next five years?

I will not be making any hasty purchases! Some of it I will use directly towards my current research. Some of it I hope to use to seed new collaborations. Some I will set aside for future projects.

I also plan to donate some of the money to help organisations that do important work related to the issues I am most concerned about.

Global migration has become a very intensely debate in recent times. In the shadow of terrorism and increasing nationalist sentiments, countries are increasingly unwelcoming of migrants -- especially from conflict zones -- how will this impact the movement of ideas, histories that have shaped the world?

I worry deeply about the increasing hostility to migrants that I witness in societies around the world: From Trump's America and Brexit Britain to Modi's India; I even see it in a small city-State like Singapore, which has tended to be very open to migrants.

I think there is a narrowing of our own horizons when we turn our backs to what is 'foreign' -- indeed, some of the most vibrant intellectual and cultural and political movements in modern history have been the product of mixture and cultural exchange.

Hostility to migration is not new.

There have been moments in world history when migration has occasioned a sense of panic: Think of the American exclusion acts of the late-nineteenth century (designed to keep the Chinese out), or the restriction of Indian migration to Burma in the 1930s, following communal violence.

In those moments, as today, broader fears about intensifying global economic connectedness channelled themselves into restricting migration as a way of asserting control.

Migrants came to be seen as the symbols of unrestrained globalisation -- when, ironically, they were often the victims as much as the beneficiaries of those very processes.

'Migrant' is a capacious term. The conditions under which people have migrated have varied greatly, and they continue to vary -- on one end of the spectrum, migration has been the result of violence and migrants have been faced by a lack of freedom and a lack of choices; on the other end of the spectrum, migration may be seen as an ongoing quest for autonomy, as people move to seek better lives, better opportunities, and new horizons.

Current discourse in many Western countries stigmatises these motivations by considering 'economic migration' As something negative -- but what could be more natural, or more human?

I cannot imagine any of the societies I know well -- whether India or Singapore, or the UK or the US -- without the multiple cultural influences that migrants have brought to them.