Magsaysay Award winner and teacher extraordinaire Sonam Wangchuk tells Claude Arpi about his journey, his fights, his hopes and how he became an inspiration for the Bollywood blockbuster.

A Teacher's Day Special.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

Ladakh has recently been in the news after the government decided to abrogate Article 370 of the Constitution and create a Union Territory for Ladakh.

This seems to have rattled Beijing no end.

Today Ladakh is euphoric; its 70-year-old demand has finally been fulfilled by Delhi.

Over the last decades, while waiting for the Great Day, some individuals have slowly changed the face of the region. One of the most prominent among them is Sonam Wangchuk (not to be mixed with his homonym, the Maha Vir Chakra awardee).

In 2018, Sonam was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay Award, an annual award established 'to perpetuate former Philippine President Ramon Magsaysay's integrity in governance, courageous service to the people, and pragmatic idealism within a democratic society'.

Over the years, Sonam has been instrumental in changing the education scene and bringing a deeper environmental consciousness in the mountainous region.

Sonam's lastest project is in higher education; he is in the process of setting up the Himalayan Institute of Alternatives, Ladakh (HIAL).

The project will be unique in several ways.

First, it will deal with the issues of the mountain context. Secondly, the university will combine academics with entrepreneurship in which the students will learn by doing and will be earning as they learn.

Claude Arpi: Sonam, you are wearing different hats; you are an educationalist, an environmentalist, a social reformer, a Magsaysay Awardee. Tell us how your adventure started.

Sonam Wangchuk: My journey has mainly been driven by empathy towards people who I thought were suffering.

When I started my engineering, I had to support my education expenses; I was then studying in what is now the National Institute of Technology in Srinagar.

As I had to finance my education, I decided to teach students.

Not that I did not have any other skills, but I loved teaching students, sharing with them my knowledge in sciences, maths or languages.

So during vacations, I started teaching students in Ladakh.

It is where I learnt about the current educational system.

At the beginning, my main purpose was to finance myself; in a way, I did it too well.

I thought that I would need one year to finance my studies, but it was so successful that in just two months I made enough money to finance my three years in Srinagar by teaching a number of Ladakhis.

This experience changed my life.

Firstly because I earned so much money, I got rid of my craze for money.

I thought that money could be made any time, if required.

I also realised that there were more important things to do than make money.

It was a blessing for me, because most young people, especially engineers at that age, are crazy about money.

Luckily, I got relieved of (this craving).

The second thing that I realise was that there was a challenge, right in front of me: the students that I taught during this winter were very bright, they could understand everything, and yet 95% of these students failed in their exams.

Claude Arpi: Why was the level of education so low?

Sonam Wangchuk: Degrees were like your passport for higher education and still 95% of the students regularly failed.

At that time, everybody would blame the students, whether it was the teachers, the parents or the bureaucracy.

I immediately realised that it was not the fault of the students, there was nothing wrong with them; in fact, they were really eager to learn.

There was something wrong with the system.

In a mountainous place like Ladakh, the text books were in Urdu.

The mother tongue was completely disregarded; after 8 years of teachings in Urdu, they would switch to English.

Claude Arpi: Do you mean to say that Ladakhi language was never taught.

Sonam Wangchuk: Yes, no Ladakhi language.

Another problem was that the teachers were totally untrained and text-books were completely irrelevant to the region.

Claude Arpi: The text books were the same as used in the Kashmir Valley?

Sonam Wangchuk: Yes, books were about tigers, elephants, there was nothing about snow leopards or apricots.

The children did not relate to them; so, I discovered that it was the system which had failed.

Claude Arpi: That was the seed for SECMOL (The Students Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh).

Sonam Wangchuk: Yes, though trained as an engineer, I shifted to education as I realized that the system needed to be changed; I saw so many of the bright minds caged.

Empathy for the students drove me to try to reform the system.

Claude Arpi: Did you face a lot of hurdles, obstacles from the administration, the establishment in general?

Sonam Wangchuk: Though we should have, initially I did not.

We used a strategic approach.

I found like-minded people and we started SECMOL.

We knew that as 21-year-old youth we could not go to the office of the commissioner or to a minister and tell them 'your system is not working'.

They would have just said: 'Get lost!'

Claude Arpi: At that time there was no Ladakh Hill Council representing the Ladakhis?

Sonam Wangchuk: Yes, it was before the creation of the LAHDC.

Initially, we started SECMOL in 1989, we were so naïve that we just tried to help the students to pass their exams, we were just teaching maths and sciences.

But soon we realized that it was not the solution, we could teach maths and sciences for 50 years, it was just repairing a broken system again and again.

Then we saw that the root of the problem should be addressed, that is the rural, the village schools.

It is where the foundations were built and these foundations were weak.

We had to work with the government to bring about changes in primarily schools.

Claude Arpi: You had to work with the government in Srinagar?

Sonam Wangchuk: No, we just said: 'let us work in one school'.

We thought that if we show some results in one school, we could advocate some larger changes.

We couldn't just say that we will perform miracles.

We chose a school called Saskpol; it was the first prototype where we experimented; we changed what is taught, the way it was taught, we trained the teachers and organized the villagers.

When this worked, we went to the government.

Luckily at that time, there was governor's rule.

More sense usually prevails during governor's rule in J&K in terms of devolution, at least for Ladakh.

The advisor to the governor who came to see our work was very impressed and he adopted our text books for government schools.

This text book is still used today.

It is how the movement for education reforms started.

Claude Arpi: Tell us about 3 Idiots. How did you become an inspiration for one of the legendary roles in a Bollywood film?

Sonam Wangchuk: Well, it is a very interesting story.

You asked me if we got problems from the establishment; I said initially not.

After a few years, our program became very very popular; it was a household name in every village in Ladakh.

Everyone was talking of Education, Education, Education.

We helped the Ladakh Hill Council to do well in the education field.

It was good, but the politicians got insecure; they thought: 'We are supposed to be the leaders, these people (SECMOL) are more popular than us.'

Similarly the bureaucrats became very upset; newspapers were writing too much about us.

They felt that we had become the masters of the government schools.

They were more jealous of our popularity.

At a point in time, they came together and gave us a hard time to the extent that I branded as anti-national with Chinese connections.

One district commissioner accused me to be anti-national.

Their idea was to scare me and get me to my knees, and that I will fall in line.

But I am not of this material.

I stood against them, I took the bull by the horns; I went to court against the government; I also went to the media about the high-handedness of the bureaucracy.

I called a press conference in Jammu to show the attitude of the bureaucrats.

I refused to just submit; I took up arms.

The press conference was attended by many media persons.

Some got interested in our work.

The correspondent of CNN-IBN studied my work and a few months later, I was chosen for their 'Real Hero Award'.

On one hand, it was alleged that I was an anti-national element with connections with China, and on the other, I received the Real Hero Award.

It was in 2008.

I went to Delhi to collect the award; there was a big function in Delhi where I met Aamir Khan.

We talked, he asked me about my work, my background; he saw the documentary that the channel had made about me, it was about an engineer who had gone to Ladakh to change the education system.

But about the film (3 Idiots) it was never disclosed to me.

I had just shared some interesting ideas with Aamir Khan.

One was about the Siachen glacier, where we spend one million dollar a day for a piece of ice; I suggested that the people on both sides of the glacier, in Nubra and Baltistan, should come on the road and stop both armies to get in that zone, they may get upset initially, but they would realize that it was a man-made issue; one side is there because the other side is there.

People from both the regions could defuse the issue and part of the money spent on the glacier could be used for education of the children who are living in pathetic conditions.

I told Aamir Khan, can you inspire people by doing a film on that.

We exchanged such ideas and a few months later, I left to France to study architecture.

One year later, I suddenly got many e-mails and phone calls, people saying the film about you is super, great, etc.

I had no idea.

It was not a biopic.

They just used my story as an inspiration and changed the script which they have been working on.

Claude Arpi: How did you shift from being an educationist to an environmentalist?

Sonam Wangchuk: It was not a shift.

I believe that today, education should be mostly about environment.

Education is about solving people's problems.

Environment is today the biggest problem in the world.

Not only here in Ladakh, but everywhere in the world; our education system shouldn't be centered on consumption and production, which caused the present mess.

It should about solving the mess.

Education is a great medium to prepare young people to deal these problems.

Claude Arpi: In Ladakh, tourism has developed extremely fast.

In one way it is good as it brings good revenue to many, but it also endangers the environment.

What is the way out of this dichotomy?

Sonam Wangchuk: Tourism itself is not the main problem.

The main problem is management of tourism, we have really mismanaged it.

What is happening today in the name of tourism in Ladakh?

Three lakhs of people descend on an area of 5 sq km, i.e. Leh in a 5 month-time.

That is a very concentrated dose for any place!

It is where the problem starts, such a large number of people, in such a small area, in such a short time.

My solution is to spread it out and increase the carrying capacity both of space and time.

In space means out of Leh, in rural areas, so that rural people do not have to come in Leh to benefit from tourism.

Make home-stay, farm-stay in rural villages, make these places more attractive for the young people to live.

Tourism benefits should come to the doorsteps of rural Ladakh; they can sell their milk, handicrafts etc.

to visitors from all-over the world; people should not be uprooted to the cities.

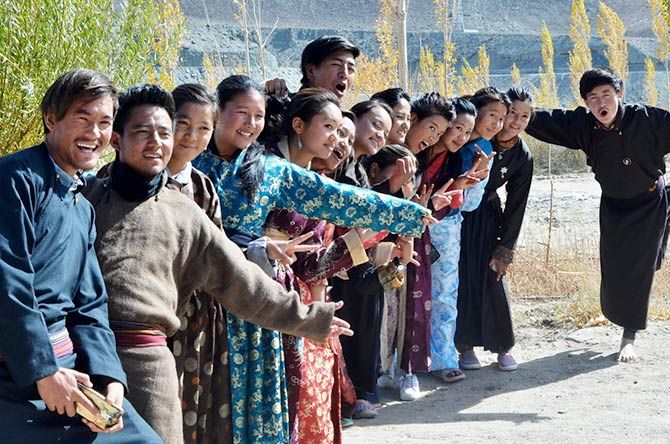

According to the Himalayan Institute of Alternatives Web site, he has already raised Rs 462 lakhs. Photograph: Kind courtesy HIAL

Claude Arpi: Do you have large scale migration in Ladakh like in Uttarakhand?

Sonam Wangchuk: It is different.

In Uttarakhand, they migrate out of the State, here they come to Leh, they remain within Ladakh.

It is slightly better, but not good.

Leh is exploding being over-populated, in the villages it is the opposite, it is an implosion.

We should spread tourism in geography (space).

Make the villages in Kargil, Zanskar, etc attractive for the young Ladakhis to live.

Supplement agriculture with tourism in the villages.

Then in time, spread tourism through the whole year, don't make it a toxic concentration during five months.

Promote winter tourism, ice tourism, ice sports, ice art, many things are possible; Spring tourism about apricots blossoming, wild roses etc.; then Autumn tourism, all year round there should be a moderate number of tourists.

Not only in Leh, but all-over Ladakh, then it won't be such a problem.

It will be good to the people; remote areas will benefit from it too; it is what I call a better management.

Claude Arpi: How did the Magsaysay Award change your life?

Sonam Wangchuk: I never thought much about awards.

There are good aspects and bad ones.

On one hand it gives you recognition, on the other hand, people who also had worked hard, are left out.

On the positive side, the Magsaysay Award is highly respected in our country, it opens many doors.

It makes things less difficult to deal with the government.

You don't have to spend so much time convincing people of a good idea, with this recognition.

It is also a great responsibility.

One should not misuse it.

Claude Arpi: A word about your ice stupas.

Sonam Wangchuk: It is an effort of the mountain people to not give up, when faced with climate change.

It is still at an early stage of development, it is not at the stage of solving problems, but it has great promises.

Apart from being an attempt to solve the water issue, it is also the symbol of an SOS from the people of the Himalaya.

It is not something we want to brag about, but it is something that we are forced to do.

We have to do our own glaciers, because the life-style in big cities is melting our glaciers.

It is a message to the people in the big cities: 'If you live simply in the big cities, we will live better in our mountains! In the cities, you have to be caring about other people. We are the first victims of your behavour, but it will soon catch up with you too.'

Claude Arpi: A last question about, about the strategic location of Ladakh, with two neighbours, Pakistan and China, at your doorstep. Do you think that opening the borders could help?

Sonam Wangchuk: There are small border disputes for few kilometres here and there; it should become smaller and hopefully completely go one day.

The countries involved should settle for something mutually agreed and then remove the military build-up.

What I want to say to the world is that India and China fighting with each other is like two neighbours fighting when an avalanche is coming.

The environmental threat is so big for both sides, that instead of getting involved in conventional disputes (and this is valid for all countries of the world), the two countries should spend their budget for mitigating, if not stopping, the effects of climate change.

We all have to work towards solving climate change.

It is the challenge of the 21st century.

© 2025

© 2025