'Under the more strident Modi version of Hindutva, Nehru has almost become a contemporary political figure.'

'The ruling party knows that without total erasure and distortion of Nehru, their fantasies will always be wobbly.'

Launching the celebrations for Azadi ka Amrut Mahotsav -- 75 years of India's Independence -- Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi said the next 25 years, from the 75th to the 100th year of Independence, would be India's Amrit Kaal (virtuous period).

In an earlier speech, Modi had said India 'wasted the first 25 years' after Independence and hence we should 'start working' for the next 25 years.

In his Amrit Kaal speech (external link), Modi said, '...in the 75 years after Independence, a malaise has afflicted our society, our nation and all of us. It is that we turned away from our duties and did not give them primacy. In the last 75 years, we only kept talking about rights, fighting for rights and wasting our time. India lost considerable time because duties were not accorded priority. We can make up for the gap which has been created due to primacy about rights while keeping duties at bay in these 75 years by discharging duties in the next 25 years.'

In 1931, during the Karachi session of the Congress, a resolution was passed listing out fundamental rights that the Indian State must adhere to, which later formed the basis of Fundamental Rights provided in the Indian Constitution. The resolution was originally drafted by Jawaharlal Nehru, but some Congress members made changes to it later.

Thus, Modi's downplaying of insistence on rights and focussing on duties instead is seen as opposite to the approach Nehru took.

However, in his famous speech delivered on the midnight of August 14, 1947, Nehru also spoke about taking 'a pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people'.

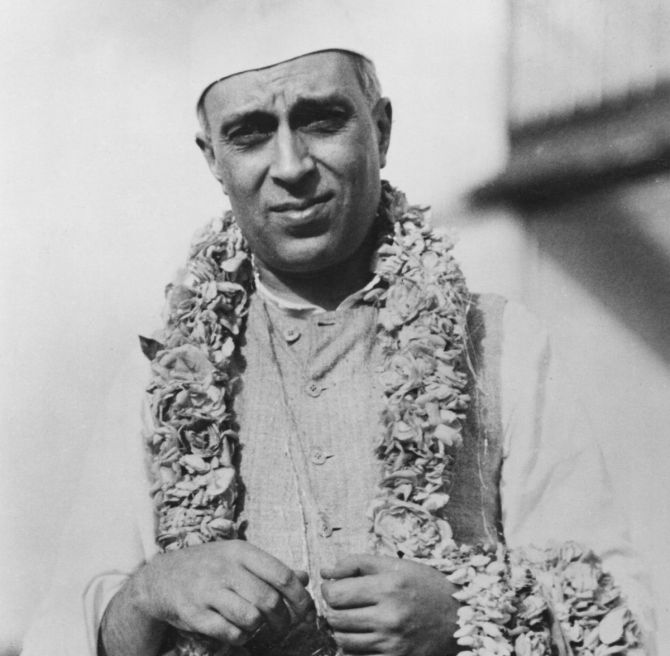

Professor Purushottam Agrawal, author of Who is Bharat Mata: A collection of writings by and about Nehru, explains Nehru's ideas on freedom, liberty, democracy and other issues and the present dispensations antipathy towards India's first PM, in an e-mail interview with Rediff.com's Utkarsh Mishra.

Nehru's two most famous speeches are 'Tryst with Destiny', which he delivered on the midnight of August 14, 1947, and 'Light has gone out of our lives', his address on January 30, 1948, after Mahatma Gandhi's assassination. We know that the latter was delivered ex-tempore.

Is it true that the former was also not a written speech as the draft of what was actually written was lost? If yes, then can you tell us more about the story behind it? How did Nehru go about his various speeches?

One of the Hindutva brigade's 'charges' against Nehru is that he chose to deliver his very first prime ministerial speech not in Hindi, but in English, and like many such 'charges' it is also false.

In fact, going by Constituent Assembly proceedings (Book 1, Tabular statement and vol. I-VI, p. 3-4), he first spoke in 'Hindustani' (the proceedings say, 'translated from Hindustani') and then read out the 'resolution' in English; the content was the same, but the speech, being ex-tempore, had a flavour of spoken word including occasional repetitions, the resolution was crisp.

This 'resolution' is known as the famous 'Tryst with Destiny' speech.

Maybe, he had also prepared a crisp draft for speech in Hindustani, but had to deliver it ex-tempore. (I am grateful to my friend Shri Piyush Babele for making this reference available.)

In Freedom at Midnight, author Larry Collins says that Nehru was informed about the bloodbath in Lahore only some time before he was to speak. He was very upset and wondered what is he going to say at such a time. Yet the speech that he gave became one of the century's greatest. What does it say about Nehru's eloquence and erudition?

Nehru was not only erudite, but also given to philosophical reflections.

He always used to put different events and trends in a larger, holistic perspective of history. The New York Times described his Glimpses of World History as 'one of the most remarkable books ever written', noting that, 'One is awed by the breadth of Nehru's culture'.

The tryst with destiny speech is a fine example of this 'breadth'.

He realised the irony of Indian independence coming with horrible slaughter.

As the leader of free India, he recognised and at the outset reminded his fellow citizens, 'we shall redeem our pledge not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially'.

In such an hour, when the elation of freedom was mixed with sorrow of human suffering, a 'philosopher king' would remind people that the full realisation of pledge will need incessant striving along with fortitude and empathy.

He refers to 'the father of nation' and ruefully notes that 'we have often been unworthy followers'.

The speech has become not only one of the country's, but one of the world's greatest due to its profound reflection, deep emotion and, more importantly, due to the way Nehru and his colleagues dealt with one of the greatest and bloodiest human crises.

Your book Who is Bharat Mata is a collection of writings by Nehru and about Nehru with focus on history, culture, and idea of India. Will you share your experience of writing the book? What various aspects of Nehru's culture did you see during that exercise?

As I have indicted in the introduction to Who is Bharat Mata, my engagement with Nehru goes back to childhood memories in Gwalior of enigmatic reactions to his demise in my immediate surroundings.

Those who castigated him in harsh terms when he was alive, looked like living pictures of grief on that afternoon of May 1964.

Some years later, I was 'introduced' to Nehru in somewhat systematic way by the late Shri Prakash Dikshit, a fine intellectual, poet and a devout Nehruvian.

Later, in the early years of this century, I turned to reflecting about Nehru in a more sustained manner.

Who is Bharat Mata was conceived during a dinner with Ravi Singh of Speaking Tiger, when I mentioned to him the deep empathy and nuanced understanding of Indian culture and tradition Nehru had, contrary to all the propaganda about his indifference, even contempt for Indian, Hindu traditions.

Choosing relevant pieces for this book was simultaneously an exhilarating and depressing experience, exhilarating due to being in presence of such an incisive mind and sensitive soul; depressing due to going through some of the dirt that has been thrown at him.

This while underlining the deliberate distortions of our collective memory, also indicates the troublesome spread of ungratefulness not only with reference to Nehru but to the whole of the national movement.

As I have pointed out in the introduction to this book, Nehru had a very nuanced understanding of spirituality, and found himself close to Advaita Vedanta view of cosmic conciseness.

In his own words, 'I have been attracted towards the Advaita (non-dualist) philosophy of the Vedanta... I realise that merely an intellectual appreciation of such matters does not carry one far... The diversity and fullness of nature stir me and produce a harmony of the spirit, and I can imagine myself feeling at home in the old Indian or Greek pagan and pantheistic atmosphere, but minus the conception of God or Gods that was attached to it. Some kind of ethical approach to life has a strong appeal for me, though it would be difficult for me to justify it logically.'

'I have been attracted by Gandhiji's stress on right means and I think one of his greatest contributions to our public life has been this emphasis.'

At other places he compares Kalhana's idea of 'Dharma and Abhaya' with the contemporary expression 'Law and order' and finds Kalhana philosophically and ethically more profound.

The allusions to episodes from Indian epics come effortlessly to him and at one place he defines a 'cultured' person as the one with self-restraint and care for others.

In short, reading Nehru has been a moving, enriching experience.

The civil liberties enshrined in the Constitution are largely Nehru's legacy. Though he's also criticised for bringing the First Amendment that imposed several restrictions on the Fundamental Rights.

How far do you agree with the proposition that the First Amendment was brought simply to let the Nehru government have its way around the constitutional safeguards and judicial scrutiny?

It is interesting that the context and one of the objectives of the first amendment has almost been erased from the public memory.

To begin with, let us just recall that Gandhiji was murdered with six months of independence -- not by a 'lunatic', but a by politically motivated man; and the home ministry, led by Sardar Patel, had to ban the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

Here is a quotation form the February 4, 1948 communique banning the RSS:

'It has been found that in several parts of the country individual members of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh have indulged in acts of violence involving arson, robbery, dacoity, and murder and have collected illicit arms and ammunition. They have been found circulating leaflets exhorting people to resort to terrorist methods, to collect firearms, to create disaffection against the government and suborn the police and the military.'

Moreover, there was armed insurgency led by the Communists who believed that the freedom is fake, it was only in October 1951 that this rebellion finally ended.

Now, imagine the difficulties faced by the nascent nation-State -- the post-Partition challenge of healing the wounds and rehabilitation, dealing with the attempts to subvert the inclusive nationalism with the communally inspired idea of nation (mentioned in the communique of February 4, 1948), the left wing rebellion and the Kashmir imbroglio.

One may still have reservations about the First Amendment, but can we dismiss the above mentioned concerns faced by the nation-State?

The other rationale of this amendment (deliberately forgotten) was about the land reforms.

To quote form Nehru's note dated May 10, 1951, 'The validity of agrarian reform measures passed by the State Legislatures in the last three years has, in spite of the provisions of Clauses (4) and (6) of Article 31, formed the subject-matter of dilatory litigation, as a result of which the implementation of these important measures, affecting large numbers of people, has been held up.'

So, the First Amendment was brought to restrict the scope of judicial scrutiny being used as 'dilatory' and delaying tactics in order to save the nascent Republic from the threats of violent overthrow and to remove hurdles from the way of reforms intended to empower the powerless.

In a recent speech, Prime Minister Modi said that 'in the 75 years after Independence, we turned away from our duties and only kept talking about rights'. He called it a 'malaise' and said that 'we will have to put emphasis on duties'.

In his address to the nation on the eve of Republic Day, President Ram Nath Kovind also said that 'the observance of Fundamental Duties mentioned in the Constitution creates the proper environment for the enjoyment of Fundamental Rights'.

How inconsistent is this approach with that of Nehru which he took in the Karachi resolution of 1931 and which later became the basis for fundamental rights guaranteed in the Constitution? He never said that to enjoy these rights one will have to fulfil some duties.

The question answers itself in the last sentence.

A democratic State does not see rights as a reward for 'doing' some duties.

In fact, the idea of citizens' inalienable (except through due process of democratically adopted laws) rights is the core of democracy.

Obviously, the present dispensation in its approach is closer to General Ayub Khan and later on General Zia-ul Haq of Pakistan who believed in the idea of 'guided democracy'.

Is this the cost our society pays for constant denigration of Nehruvian legacy by the people in power and their supporters that even the insistence on civil liberties becomes a 'malaise'? That being 'secular' is now seen as a bad thing? Because when you oppose Nehru, you oppose everything that he stood for. And you try to undo the impact he had on our society by maligning him.

You are absolutely right.

We must recall that the Indian freedom movement also had a self-conscious international dimension largely due to Nehru who imagined Indian independence as part, in fact as harbinger of worldwide, peaceful uprising against imperialism.

He deeply hated the 'strange ideology of Fascism and Nazism' and all its variants.

He was instrumental in leading Congress to strive for full independence instead of dominion status.

It was not for nothing that Lee Kuan Yew described Nehru as the 'first of Afro-Asians'.

Along with this international perspective, Nehru acquired an authentic understanding of Indian traditions and cultures through deep study and constant political activism, he established a unique dialogue with his people.

The Hindutva right wing hates him, and beneath their hatred lurks a very deep fear of Nehru.

That is why, under the more strident Modi version of Hindutva, Nehru has almost become a contemporary political figure.

The ruling party knows that without total erasure and distortion of Nehru, their fantasies will always be wobbly.

Nehru had a forward-looking sense of history, he knew that 'you can not ignore your past and yet you can not live in it'.

He realised the importance of the nationalist sentiment as well as the possibility of it being used as a tool of most regressive and reactionary politics.

On one hand, he chided the communists for their lack of understanding regarding emotion of nationalism; on the other hand he constantly warned against communalism (which he saw as an Indian version of Fascism) masquerading as nationalism.

He used the metaphor of a palimpsest to describe Indian cultural experience, which conveys its historical dynamics much more convincingly than the better known metaphor of an ocean used by (Rabindranath) Tagore.

After the PM's announcement of installing a grand statue of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose at India Gate, once again a lot of falsehoods are being spread about Nehru-Bose relations.

Why does it always have to be at the expense of Nehru that some other leader like Patel or Bose or Rajendra Prasad is honoured? Why can't they just say that they were great?

They have to add that Nehru 'disrespected' them and 'their contribution was more than him'.

I have partly answered this question above.

Due to pathetic fear of Nehru in their minds, no low is low enough to denigrate Nehru as a public figure and even as a human being.

Moreover, the petty minds find it very hard to understand the political differences going along with mutual affection and respect.

They opened the Netaji files with much fanfare and great expectations of denigrating Nehru and what they found there? Nehru caring for and arranging for Netaji's wife and daughter without making an event of it.

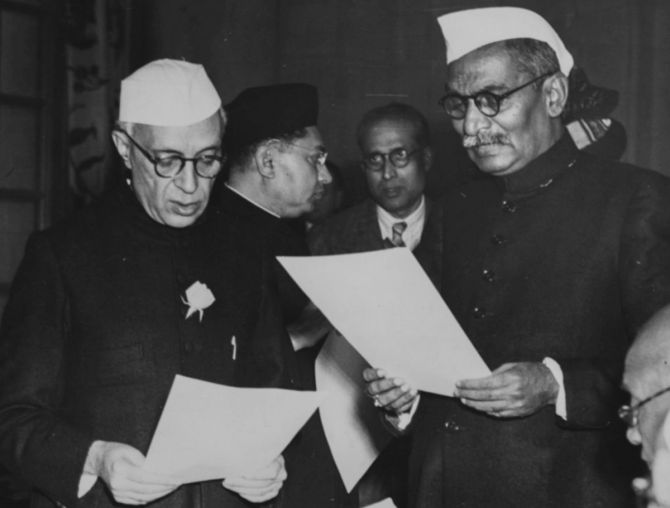

Similarly, they won't care for Patel describing Nehru as the 'leader of our legions' or Rajendra Prasad taking the initiative of conferring the Bharat Ratna on him bypassing the usual protocol.

I would not be much bothered if all this was merely a spiteful denigration of an individual, but it is infinitely more insidious; Nehru's denigration is integral part of larger design of subverting the very notion of Indian nationhood and reconstructing Indian society as a nightmare of hate-filled fascistic fantasies characterised by constantly excitable and aggressive mindset and its violent manifestations.

© 2025

© 2025