'He needs to get out of the gate fast.'

"There is a long to-do list from streamlining and expanding the goods and services tax, to tweaking the new bankruptcy code, to implementing new legislation to modernise financial services and banking in India."

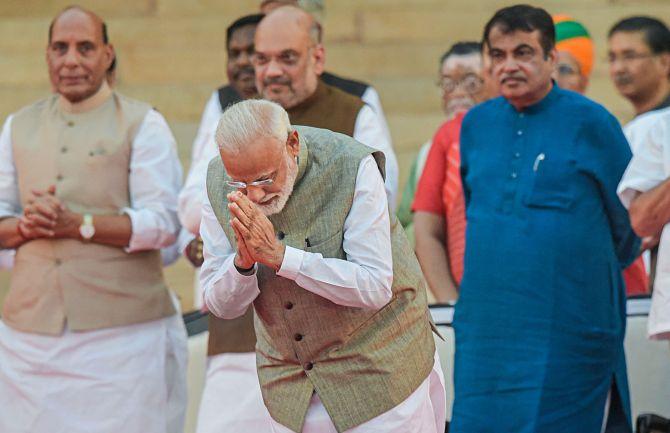

Milan Vaishnav, Director of the South Asia Program and Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for Peace in Washington, DC, discusses the Election 2019 verdict with Rediff.com's Archana Masih.

What is the message of the 2019 verdict? How different is it from 2014?

The 2019 verdict served as an unequivocal referendum on Modi's leadership and the PM passed with flying colours in the eyes of India's voters.

There is really no other way to put it. I think leadership was in some ways the top-most issue on voters's minds, even above concerns of the economy, national security, and so on.

In 2014, the voters were frankly fed up with the Congress and the pervasive sense of paralysis, entitlement, and corruption. They delivered a strong blow against the Congress in 2014.

Five years later, Modi once more was able to turn the election into a presidential contest that pitted him against Rahul Gandhi and a bevy of Opposition forces. This framing works entirely to Modi's advantage.

Right now, there is no leader who comes even in the vicinity of Modi when it comes to overall favourability. That is not to say that BJP voters are fully satisfied with the Modi government's performance, but they are willing to give him another five years to iron out the kinks.

Modi's plea that he cannot undo 65 years of history in five years is frankly a pretty good sales pitch. The voters seem to agree.

He has started an ambitious project of using government resources to provide private goods -- from gas cylinders to toilets and electricity connections -- and voters would like him to see this project through.

You had presciently told me in an interview in February that the 2019 election would be fought on nationalism, not on Hindutva.

Did the BJP's message of nationalism entwined with Hindutva bring about such a decisive victory?

There are several strands of nationalism operating in India at the moment.

The first is Hindutva or a majoritarian stance on how Indian society should be governed in the future.

The second is a more abstract nationalism that emphasises India's sovereign territory, patriotism, and loyalty above all.

The third is a muscular, outwardly-focused nationalism which centers on India's role abroad.

All three were at play this election, but I think the second is something the BJP has emphasised in recent years at the expense of the first.

As Suhas Palshikar has argued, this mundane form of nationalism is much more palatable to voters who may not necessarily buy into the Hindutva project.

It is about country first. Later, the party can make the argument that a 'good Hindu' is a 'good nationalist',' this is not the point of entry.

The third strain of nationalism came on heavy in the wake of Pulwama when India came under attack from terrorist forces based in Pakistan.

I don't think we can boil the victory down to nationalism alone -- that would be too simplistic and voters are far too complicated for such reductionism.

But it certainly played a part. I have argued elsewhere that Balakot essentially gave voters an 'excuse' to vote for Modi. They liked him anyway and this reinforced their predilections.

What have been some unexpected outcomes of this election?

For starters, many analysts called 2014 a 'black swan' election. Well, it is not a black swan if the result is replicated twice in a row!

It is now the 'new normal'. So the size of the BJP's mandate, of course, is the biggest surprise. Most election observers, including myself, predicted the BJP would come back -- but the scale is stunning.

Second, it is surprising that the Congress could not translate any of the gains it made in December 2018 into an advantage in the Lok Sabha polls.

History tells us that the assembly polls, which occur right before the Lok Sabha polls, tend to predict the outcome reasonably well in those states. I thought the gains would certainly not be as large given the Modi factor, but I also did not think they would be basically zero.

Third, for the past six election cycles, there has been a 50-50 split in vote share between the two national parties (BJP and Congress) and all other regional parties.

This time, the regional party vote share dipped to 41 percent. The Congress percentage essentially did not change and the BJP share surged. This tells you that there has been a certain amount of re-centralisation in the political system.

In what ways can such a decisive second mandate change the BJP's politics and in turn change India?

This is the million dollar question. I would look at two angles.

First, there is no question that the Nehruvian concept of secularism has been pretty effectively discredited. That does not mean secularism as a concept is done with, but the way in which it has been put into practice will likely change.

The BJP will have wide latitude to reshape the relationship between religion and politics and take things in a more pro-Hindu direction, as its manifesto promises to do.

Whether it is replicating the National Register of Citizens outside of Assam, passing the Citizenship Amendment Bill, or implementing the cultural project of rewriting textbooks, interfering in dietary habits and so on, these are all things the Sangh Parivar hopes to achieve in a second Modi term.

Second, with respect to the economy, it is frankly not clear how the BJP wants to move. It adopted a cautious, incremental, reform programme in the first term. This reflects Modi's own inclination as well the reality of India's traditional veto players (the courts, the Rajya Sabha, Centre-state relations).

Modi will undoubtedly continue with his pro-business agenda, but the real question is whether it will be pro-business or pro-market. In his first term, he tended to tilt towards the former.

What are the top 5 takeaways from the 2019 result?

First, we have decisively entered the 'Fourth Party System' in Indian electoral politics.

The post-1989 era of fragmentation has ended. 2019 is confirmation of the trends we first saw in 2014.

The BJP has replaced the Congress as the central pillar around which politics revolves, plain and simple.

Second, the Opposition suffers from the same infirmities that plagued it in 2014: absence of credible leadership and a lack of a clear, affirmative vision for the country.

Third, regional parties were on the ropes in 2014, as evidenced by the BJP's absolute dominance in the Hindi belt.

In 2019, 'regionalist' parties -- those parties that mobilise on the basis of a subnational linguistic and cultural identity -- have also suffered.

The BJP's ability to make serious inroads in the East in Bengal and Odisha and in Telangana speak to this.

Fourth, dynastic politics has not been defeated.

Yes, the Nehru-Gandhi avatar of dynastic politics is on life support, but 30 percent of MPs elected in 2019 have dynastic backgrounds -- including 22 percent of BJP MPs.

This is a representational style in Indian politics that is decidedly not on the wane.

Last, but not least, we cannot discount the role of money.

This is probably the most lopsided election we've ever seen in terms of the resources one side possessed compared to all others. It is hard to quantify the size of this effect given the opacity of election funding in India, but it undoubtedly has played a role.

What are the challenges that confront Modi in his second term?

The economy is the biggest challenge.

Voters have real economic grievances, but they would like to give Modi more time and believe that his leadership will be crucial in redressing those challenges.

Unlike 2014, Modi cannot afford to get off to a slow start.

This is why the rumblings out of Delhi about a 100 Day Plan are actually a good thing. He needs to get out of the gate fast.

There is a long to-do list from streamlining and expanding the goods and services tax, to tweaking the new bankruptcy code, to implementing new legislation to modernise financial services and banking in India.

There are larger reforms too that Modi must contemplate and I would hope that he augments his strategy by really pushing the BJP/NDA states to lead by example.

One missed opportunity from the first term is that Modi never really used the collective power of the NDA states to push for reform (save for their weight in the GST Council).

As a former chief minister, I would have expected him to move in this direction. There is still time to do so.

Last, but not least, India is badly in need of administrative reform that upgrade the bureaucracy, police, and rule of law functions. These are in some ways the most important economic reforms even if they are 'economic' in a narrow sense.

These were not priorities of the first term, but they ought to be in the second term. We know what needs to be done; innumerable government panels, commissions, and expert committees have already told us.

The issue is about leadership when it comes to implementation.