'There are some castes that grab power, then pass on the benefits to those who belong to their own caste.'

'Society still does not accept women leaders unless they are thrust upon people from the top.'

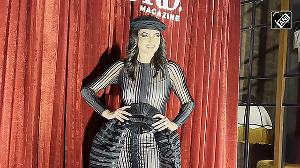

P Sivakami plays many roles -- writer, former IAS officer and now a political leader all set to give voice to the Dalits of Tamil Nadu.

After 29 years in the civil service, she took voluntary retirement so that she could be active in politics. She joined the Bahujan Samaj Party and contested the 2014 Lok Sabha election from Kanyakumari, but lost.

She has now founded a political party, the Samuga Samathuva Padai.

Unmaikku Munnum Pinnum, her latest book, is the fictional account of the life of a Dalit IAS officer, Neela. It has been described as the first Tamil work on a bureaucrat's life.

Her earlier novels, Grips Of Change and The Taming Of Women, were translated into English and much appreciated.

Sivakami spoke to Shobha Warrier/Rediff.com about her journey and her future plans.

A woman Dalit police officer, Vishnu Priya, committed suicide some weeks ago, reportedly because of the harassment she faced from her superiors. The protagonist in your book is a Dalit IAS officer. You have described how her superiors made her life difficult. Do you feel the Indian bureaucracy is Brahminical?

I would use the word casteist.

Being Brahminical is different from casteism. There are some castes that grab power and then try and pass on the benefits to those who belong to their own caste. That is what is happening (today).

Of course, Brahminism helps them justify their stand.

In Vishnu Priya's case, we will know the truth only after a proper enquiry.

In my novel, Neela faces much more harassment than Vishnu Priya.

Is Neela a fictional character or is she autobiographical?

The book has 90 per cent of my experiences, but I had to leave out certain things. A novel need not be completely true. My book is a fictional story about Neela, a Dalit IAS officer. It is not an autobiography.

Neela was given a lot of memos and she ran from pillar to post trying to justify her actions. I have written just about Neela. In reality, every officer belonging to the Dalit community faces similar atrocities.

More than the officers who are in the public eye, it is the others who go through more stress as they are suspended, victimised and ignored when it comes to promotions. At times, they even have to report to subordinates.

All this does happen when you don't toe the politicians' line as well, but it happens largely to Dalit officers.

Is being a Dalit woman a double disadvantage?

There is a disadvantage. It was only after MGR (Maruthur Gopalan Ramachandran, Tamil movie superstar and founder of the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazagham, the AIADMK party) became the chief minister (in 1977) that lady officers were posted as collectors.

For many years, women were not posted as home secretaries or to any such important portfolios. Later, they did get an opportunity. The number of women in the civil service also was less.

When I joined in 1980, only 15, 20 of my 120-strong batch were women. There is a marginal increase in that percentage now.

However, it is still true that, compared to men, women hold comparatively less important positions.

When you joined the civil service, what were your dreams? Did you expect the kind of discrimination you faced?

To be frank, I had no idea what to expect.

As a student, I wrote many exams, including the civil service exam.

My father was an MLA and he had seen the power that collectors had. That is why he wanted to make me an IAS officer.

I was a good student. After I finished my post graduation, I started looking for a job and thought joining the IAS was a good option.

So you realised your father's dream?

The civil service exam is a challenge for a good student. I looked at writing and passing the exam as a challenge. I didn't dream of becoming a collector or enjoying the power associated with it, I only had the exam in my mind.

When I joined the service, I saw a lot of discrimination. Most people had godfathers, I didn't.

Had your father warned you about the discrimination?

Had your father warned you about the discrimination?

(P Sivakami, left) He didn't know about it as he was not a very educated person.

Was it a shock for you?

No, it was not a shock. By then, I knew our society was full of differences.

I thought if you were meritorious, you would ultimately be rewarded. I worked hard for whatever I got. Even as a collector, I was transferred because I didn't listen to politicians.

It was when I became secretary, Adi Dravida Tribal Welfare, that I realised something else worked behind the government machinery. I was not aware of that earlier.

Earlier, I headed the tourism department for eight long years and I was posted in Tokyo for three years. But as the secretary of Adi Dravida Tribal Welfare, I was serving the poorest of the poor.

Did your superiors treat you on par with the others? Was there any difference because you were a woman and a Dalit?

You can't express it, but you feel (the difference). I have described it in the novel.

It is so minute that only those who are sensitive will feel it. It is like going to a wedding, but not finding anyone you can talk to. You can't say it is harassment, but you don't feel alright. You feel isolated and not part of the crowd.

This is the kind of feeling the service gives you, that you are not part of them.

A group may be discussing an issue, but when you express your opinion, nobody listens and they turn to another person. They don't even realise you want to say something. You are ignored.

I can't say it is because of one's caste, but you are made to feel ignored. You are made to feel that you do not have the capacity to make people listen to you. On the other hand, if you are occupying an important chair, irrespective of the caste, people listen to you and recognise you.

Which is difficult to overcome: Caste identity or gender identity?

I will talk about how Neela dealt with it. She understood her happiness lay elsewhere, unlike her colleagues who saw the job as a way to get more powerful posts. Other than that, she found they had no social commitment.

Neela was an idealist so she could not ignore the way her colleagues insulted her.

While her feelings were permanent, my feelings as a living human being are temporary. You go through ups and downs and, with that, your feelings also change.

Neela withstood everything and found happiness elsewhere. The book is not completely autobiographical that way.

Did you dream of becoming Neela?

I wanted to be more than Neela.

How much of your dreams could you achieve?

The novel ends with the chief minister punishing Neela with an unimportant post, but she didn't want to get punished. She had already found happiness in writing and in working for the Dalits.

We see a lot of similarity between Neela and you...

Of course, there is a lot of similarity.

She didn't leave the service, but I left to work for the Dalits. In fact, Neela argues with the chief secretary when he asks why she didn't resign to do social service. She replies saying she prefers the Neela model.

Why did you resign?

I was trying to understand my role, my aspirations. I felt my services were needed elsewhere and not in the government.

In the political arena, there are many competitors, but no examinations. The only test is your ability to mobilise people. The real challenge is getting the acceptance of people. You may think you are doing wonderfully well, but it is only if you are accepted that you can do well.

Compared to the challenges faced by a leader, the challenges of an IAS officer are nothing. I use the word 'leader', not 'politician'.

Society still does not accept women leaders unless they are thrust upon people from the top.

How tough has it been to get the acceptance of people?

Very, very tough. When you start a political party, it has to be different.

You first joined the BSP and later chose to start your own party. Why?

The BSP is very Uttar Pradesh-centric. They mobilise resources from here and use it there.

I left a very important service to be in politics, but I soon found that my energy was not utilised properly. I felt I would vegetate if I continued there (in the BSP). That's why I decided to start my own party.

Without being in power, how long can you run a political party and be of service to the people?

The lowest strata of society, irrespective of caste, faces a lot of difficulties. They long to have a leader who will help them fight corruption, rising prices, etc. But you have to make them realise that you are the one who can deliver. If you target the group correctly, you can increase your strength.

In the case of Dalits, they still are dependant on Hindus for their living. They decide the Dalit votes, that's why Dalits vote for either the AIADMK or the DMK.

My duty is to show them there is a way out.

The Left parties also have succumbed to power politics, their sole aim is to capture a few seats.

Thirumalvalavan is trying to bring the Dalits under his umbrella...

Thirumalvalavan (Dalit activist, MP and president, Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi party) has not been able to develop a strong cadre yet. It is a typical Dalit situation. His party has already fallen in line with the other Dravidian parties.

We have to create a different model. You need political and ideological commitment. You need to spend your own money to build your party.

As an individual, will you be able to do this?

I am not just an individual. When I left the service, I was an individual. Now, I have a political party, the Samuga Samathuva Padai, and a strong cadre. We work in 12 districts in Tamil Nadu.

Wherever I go, I am accepted.

Yes, my cadre is very poor, they are daily wage earners. My challenge is to make a cadre of the very poor, voiceless, people. You have to be alive, kicking and talking continuously as a political party.

(BSP President) Mayawati had (the late) Kanshi Ram as the leader who did all the ground work. She only took over. In your case, you had to start from scratch. How tough was it?

It was very tough. When I was in service, I ran a movement. That helped me initially. After I floated the political party, most of them accepted me, but few had doubts about accepting a woman as the leader.

But if you have time, you can withstand all these problems.

How much time have you given yourself?

Twenty years. I just completed six years of my political career.

At any point, did you regret leaving the civil service and starting a political career?

In fact, I am happier. I only regret not starting down this path 10 years earlier. I should have done this when I was a collector. At that time, the field was vacant as Thirumalvalavan had just entered.

If I had taken the decision to enter politics then, I would have had a better innings.

Is this the toughest job you have taken up?

Yes, the toughest. When in service, you can depute others. You get guidance. Here, you have to struggle by yourself. If you take a wrong decision, it will be very difficult to set it right. It is like taking an examination everyday.

It is said that with, literacy and education, caste differences should disappear, but if you go to a village in a literate state like Tamil Nadu, you see that Dalits are still kept outside the village. Why is it so?

Dalit habitats are kept a little away from the village. Neither the Tamil Nadu government or the Indian government has done anything to bring them together.

The government is not helping by clubbing a Dalit village and the other parts together. The caste Hindu will always be the Panchayat president. In the name of unity, they grab power from the Dalits.

When the World Bank drinking water project came, I said there should be a separate project for the Dalit habitation, but they refused saying the government would not allow it.

All the drinking water facilities are inside the caste villages. I know Dalits are not allowed inside the village to make use of the facility.

Sixty years have passed (since Independence). Has reservation served its purpose and benefitted many people? The criticism is that the beneficiaries are continuing to get the benefits of reservation and denying (it to) those who really need it.

It takes three generations for a family to come out of reservation. I have taken the decision of opting out of reservation for my children.

But even today, many are not getting the full benefit of the existing quota of reservation. They should also talk about that. It is only when you implement reservation everywhere that you will be able to say how long you need it.

As long as the caste system continues, we may need to continue with reservation. The poor can come up only if reservation is implemented in the private sector as well.

Look at who is making use of the rivers even now. The caste Hindus. Dalits are not even allowed to bathe in them. Who has all the fertile lands?

Do you hope to see a change in your lifetime?

It will happen, but not in my lifetime. If Dalits are educated and organised well and are able to share political power, a change will take place in their lives too.

P Sivakami's photograph: Ramesh Damodaran.

© 2025

© 2025