'Partition was a two-sided story in a very big way.'

'We've oversimplified it, blamed the British, thought of ourselves only as victims.'

'We've been both victims and perpetrators.'

Can Partition ever be forgotten? Do only Punjabis and Bengalis make a big deal about it?

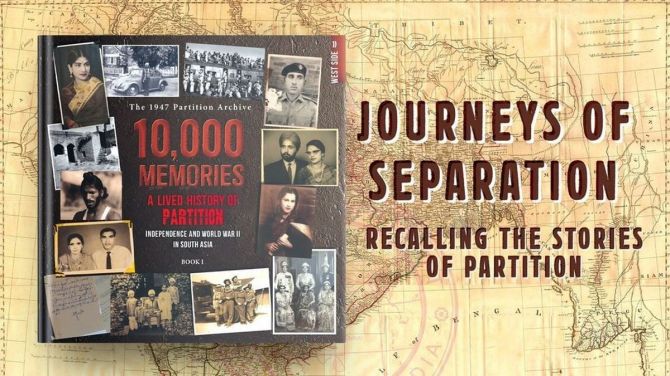

Popular myths about the cataclysm that shook the subcontinent have been busted by the stories collected by Guneeta Singh Bhalla and her team for her brainchild, the 1947 Partition Archive.

So far, 10000 stories in 36 languages have been collected; 400 of them will soon be out in a book, titled 10.000 Memories, A Lived History Of Partition.

In India to promote the book, Bhalla, who lives in California, spoke to Jyoti Punwani about what drove her to give up a career in science to chase Partition survivors, and what she learnt.

What made you change from pursuing science to documenting memories of Partition?

Most of the stories my grandmother used to narrate I could not find in my history book. There it was all about peaceful transfer of power in 1947. That didn't match what I'd heard from her. When I asked my history teacher about this, she told me my grandmother must have been exaggerating.

Also, it occurred to me that we spend so much time learning about the Holocaust, but we know nothing about our own holocaust. After I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial in Japan in 2008, I had this absolutely overwhelming desire to record whatever I could about Partition for the future.

The traditional archives are no longer adequate. The colonial government had made those; they lacked a diverse dataset. Newspaper archives were there, but in the early 1900s newspapers were highly polarised.

We need to hear the Partition story from lots of perspectives, through lived memories. Today, we are more empowered to be able to do so because of the internet. This archive will close the gap between the people's history and official history.

Partition is a massive part of our history. We are what we are because of it. It's part of my identity too.

It's also the source of a lot of problems we face even now. But instead of doing any meta analysis of it, we've just been blaming each other. I felt very strongly that we must go into the future on a very logical footing, and for that, we need to get to the bottom of it.

How did you go about getting survivors to talk? You started with your family?

There is nobody left in my family now who lived through it. I just started with complete strangers.

While visiting Punjab in 2009, I was in Faridkot, in an old bookshop, talking to the owner about my visit to the Hiroshima Memorial and how it had made me want to document Partition memories. He told me that was a very good idea, and I could start with him. As we were chatting, more people walked in and wanted their stories recorded. In the end, I couldn't record the owner's story!

After that, many others from nearby villages started requesting that I record their stories. I realised there was a need for this.

What did your parents think about your decision to pursue this? Had they migrated too?

My father migrated as a baby; my mother was born in India.

They thought it a waste of time after I'd studied so much! They didn't want me to waste my PhD. Not a good idea to give up your career, they said.

So no one in your family supported you?

When I was young, my Mamaji would find ancient coins and lament that India had no culture of preserving its heritage. Your generation should do so, he would tell me. So I feel I did what he wanted me to do. He seemed happy about it.

How did you pursue this obsession when you returned to California?

After that visit, when I went back, I went to a temple and put up a table where people could sign up to tell their Partition stories. That very day, people started lining up.

I realised I couldn't do this alone. So I put up signs all over the campus (University of California, Berkeley), and at shops all over the San Francisco Bay Area calling for volunteers.

How did your boss react?

My professor (I was a post-doc) wasn't happy, obviously, with my decision to leave. He requested me to stay on for six months more, probably hoping that I would change my mind.

Did you not enjoy science, or your post-doc?

I loved it. I could have got an amazing job had I stayed on. I had a great invitation I was inclined to accept to work in a lab with a Nobel Laureate. It was almost a dream job. But Partition witnesses were quietly calling.

Even two years after I'd left physics, I heard from the lab of the Nobel Laureate, asking if I would return to physics. But as I said before, I felt I just had to do this.

Could you get volunteers?

Oh yes, all kinds. Interestingly, in the beginning, most of the volunteers were non-desis. The desis were not that interested in history, till the project caught on after an article in the New York Times in 2013.

Americans were fascinated; they're not communal -- I'm talking about those on university campuses and the more metropolitan areas (the same majority who voted for Obama). They just thought, India had so many different cultures; and this was a missing chapter in world history related to that, one they were not likely to read.

While the younger desis weren't too keen, we had Partition witnesses themselves recording each other's experiences, people in their 70s and 80s.

It's been 13 years now, and a lot has changed. Now we have individuals from all walks of life, all ethnic groups across the Indian

subcontinent and beyond, and all age groups who do this work.

Interestingly, out of our core team members, other than myself, none of them has anyone in their families who went though Partition. Yet they feel deeply passionate about this work, as I do. They approach it as a chapter of a hidden history, an untold story.

You said Partition is a part of your identity. Can you elaborate?

The way that I am; the type of people my grandmother and father were. These things influence you. Who you are, where you came from... Am I from India or Pakistan or Punjab which lies in both? What's my heritage? It's ingrained in my identity.

My father loved giving away money he didn't have. Obviously, they came from a wealthy family before Partition, and he couldn't let go of that habit of generosity, a hallmark of generational wealth that he had inherited, even though he couldn't afford it. It also meant he had zero savings upon retirement.

Lahore, where my family came from, is the city where my DNA was shaped over hundreds of years, literally, because genes are shaped by our environment.

I first visited Lahore in 2015. It was a mind blowing experience. I could see my family's old home, it had become a government complex. I came back with so many gifts, I had to buy a second suitcase.

What were some of the stories that have stayed with you through this project?

The orphans. There were so many children orphaned by the violence during Partition.

We met a gentleman who was adopted after having been orphaned, taken to Pakistan by his extended family, and made to work for them. Ultimately, he managed to get an education and leave. Here in India, many Muslim orphans were "adopted'' but made to live on the farms of Sikhs and Hindus as farmhands, well into old age.

There was an auto driver in Punjab. He was 11 when he was orphaned. He couldn't continue going to school. He did odd jobs and ultimately ended up as a rickshaw driver. He remained unmarried because I suppose it would be hard to marry with no family and community support.

He must have been very bitter.

No, he was the most loving, grateful person. A Sikh originally, he worshipped all three faiths and believed everyone should live in harmony.

What do you think of the government's decision to observe August 14 as 'Partition Horrors Remembrance Day'?

That really was very interesting.

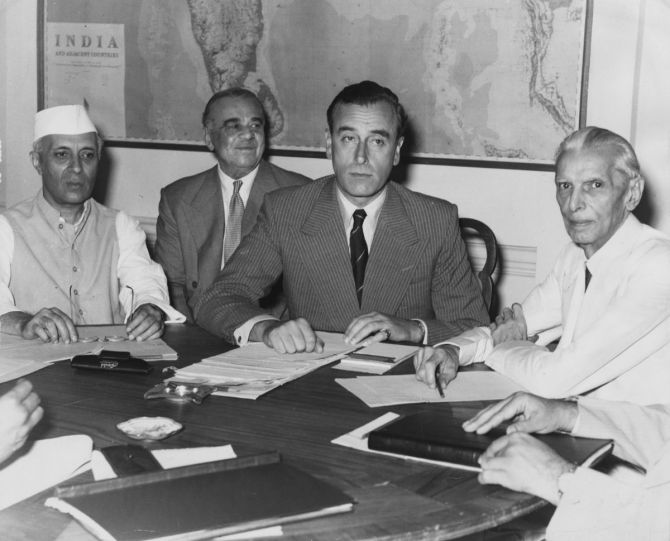

On July 27, 2021, we at Berkeley announced our decision to observe June 3 every year as Partition Remembrance Day. It was on June 3, 1947 that the Mountbatten Plan to partition the country was announced.

We announced this jointly with the mayor of the city of Berkeley and the city council, who declared it as an official commemoration in the city of Berkeley.

Exactly 10 days later, the PM of India announced that the birth date of Pakistan, August 14, would become 'Partition Horrors Remembrance Day'.

Ours was meant as a neutral observation of the day. Our Archive is flat, open to any perspective. The Indian government's observation of August 14 has a certain perspective.

Did Partition survivors blame Nehru and Gandhi and the Congress for it?

Not everywhere, but yes, in Punjab and Delhi, even in Bengal, they did. In Punjab there were strong local leaders in the Unionist Party, leaders like Baldev Singh and Allama Mashriqi's Khaksar movement, among others, which opposed Partition. Bengalis tended to follow Subhash Chandra Bose.

Did recording these stories change your perceptions?

100%. Everyone who works on this project seems to get humbled. Many of us had very strong views before we started recording the stories.

I can talk about myself: I used to be very angry with the British for having made my parents go through all that suffering. But when I studied the period in detail, my anger eventually melted away. They were simply outnumbered, they had to get out as fast as possible.

After WWII, they were bankrupt. The jails in India were overflowing; they couldn't handle the freedom movement or the riots; they just didn't have the resources or the manpower. Their own citizens back home were starving. The Congress wanted them out as soon as possible, they were happy to go.

Another thing we realised was not everybody was unhappy with the British Raj. There were businessmen who flourished; soldiers who fought in WWII who were very close to their British counterparts.

We also realised Partition was a two-sided story in a very big way. We've oversimplified it, blamed the British, thought of ourselves only as victims. We've been both victims and perpetrators.

This project helped us to confront a complex past; and I hope those who read the book will also be forced to do so.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025