'The skills and abilities of civil servants are still respected, even though they become whipping boys when things go wrong.'

After Aatmanirbhar Bharat, it is Mission Karmayogi.

According to the central government, it is the biggest bureaucratic reform initiative, one aimed at capacity building of government employees to make them more 'creative, proactive, professional and technology-enabled.'

According to a government statement, 'The core guiding principles of the competency-driven programme will be to support a transition from 'rules based to roles based', HR management to prepare the Indian civil servant for the future.'

'A council, comprising select Union ministers, chief ministers, eminent public HR practitioners among others and headed by the prime minister, will serve as the apex body for providing strategic direction, while a Capacity Building Commission is also proposed to be set up,' Press Trust of India reported.

But what does the bureaucracy feel about the reform measures?

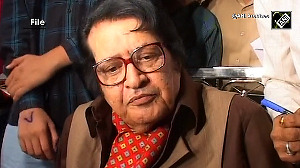

"The system has to be result-oriented rather than process-oriented," K M Chandrasekhar, a 1970 batch IAS officer who retired as Cabinet Secretary, tells Shobha Warrier/Rediff.com in the first part of an enlightening interview.

According to the Union Cabinet, Mission Karmayogi is the biggest reform initiative to make the bureaucracy more creative, productive, professional and technology enabled. Do you think they are lacking in all these?

From what I have been able to read in the media, a new portal called iGOT-Karmayogi will be opened with a menu of options detailing various programmes available all over the world.

Depending on her area of expertise, each officer at all levels from assistant secretary upwards can develop skills in her/his area of interest.

The capacity building undertaken by the officer will be taken into account in the posting/promotion/empanelment process.

If this process leads to developing officers in particular streams, rather than posting them on a random basis, this could be helpful.

However, the central and state governments contain a wide array of jobs. A system which is premised on the officer choosing areas of interest could lead to too many of them choosing popular areas like finance and international trade.

When vacancies arise in agriculture or health or education, we may not find the best officers with requisite skills.

This does not mean officers lack skills. Officers today join the civil service at a much higher age, often with professional skills acquired in the best technical institutions in the country.

Updating and enhancing skills, however, is necessary in all professions, public service included.

Indeed, many of them on their own acquire such skills which, combined with their political interface and experience of man management in different kinds of situations, make them prized acquisitions even in the private sector.

A friend recently sent me a list of 92 serving IAS officers, regular recruits appointed through the UPSC process, who moved into the private sector of their own volition in the past few years.

The central council of ministers contains at least three former civil servants, one of them an important Cabinet minister.

When the state of J&K became two Union territories, the government turned to two civil servants, one serving, the other retired, to serve as lieutenant governors.

All this indicates that the skills and abilities of civil servants are still respected, even though they become whipping boys when things go wrong.

What kind of reforms does Indian bureaucracy need?

I think it is necessary to go deeper into the reasons why public service delivery is not as quick or as prompt as is desirable.

I think it is necessary to go deeper into the reasons why public service delivery is not as quick or as prompt as is desirable.

We make the cardinal mistake of blaming individual officers or the civil service collectively for shortcomings in public administration.

The fault lies not with the individuals, but with the system.

The system has to be result-oriented rather than process-oriented.

If officers are judged by tangible, measurable, results rather than adherence to processes, the same bureaucracy, the same set of officers, can be remarkably efficient agents of change.

We saw how quickly civil servants changed their approach after the reforms of 1991, how they became advocates and instruments of liberalisation after having worked for many decades in a stifling regulatory environment.

We can see the changes that have taken place on the diplomatic front as we moved seamlessly from non-alignment to multi-alignment.

We see how internal security changed dramatically after the dark period in the nineties and the first decade of this century.

The fault lies not with the officers who man the ministries or state governments, but with the system.

Lateral entry into government service is not new. There have been many who entered government laterally. They could not make any significant impact as they were working within the same system.

Obviously, any system that is focused on results will also have to be flexible, it should trust its officers and the overwhelming fear of the three Cs (CAG, CVC and CBI) plus other sundry regulatory and investigative agencies must vanish.

On the other hand, if the officers are judged solely by the achievement of results, we can expect remarkable transformation of public administration.

This is not a new concept. Margaret Thatcher revolutionised the public administration system in the UK through the introduction of New Public Management, which was carried to still greater heights in Australia and New Zealand.

In fact, the system evolved, maturing from New Public Management to New Public Governance and later incorporated digital governance.

The heads of departments are required to sign MOUs with their ministers on what they propose to achieve within a specified time frame and the cabinet spends more time on reviewing achievements against agreed targets.

A great deal of autonomy is given to the heads of departments, including, in some countries, the right to hire and fire employees.

In India, we started with a similar exercise through the Results Framework Document system in 2008, but it floundered and died after a few years for lack of bureaucratic support and political will.

However, a number of other developing countries seriously took it up under the aegis of the Commonwealth secretariat, and I am told it has made much progress in neighbouring countries Bhutan and Bangladesh.

© 2025

© 2025