'Pollution acts as an endocrine disruptor.'

'When it acts as an endocrine disruptor it has an effect on the endocrine system of the human body and the effect on the pancreas is an important one.'

'The way you get type two diabetes is due to two defects.'

'One is the pancreas doesn't produce enough insulin.'

'The other physiological defect is insulin resistance.'

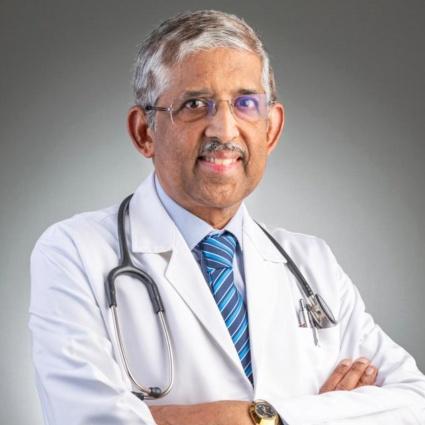

Dr Viswanathan Mohan's phone hasn't stopped ringing, and his e-mail box keeps buzzing with new messages, ever since, in an article, The Guardian outlined the startling details of a study he and his co-authors published in October in BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care that is of great importance to India

Their paper highlighted the research done to establish the link, epidemiologically, between exposure to air pollution (particularly PM 2.5 particles) and the increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

Television channels have been seeking interviews with Dr Mohan, calls have been coming in continuously and recently Congress MP and former Union minister Jairam Ramesh warningly tweeted about their research.

As winter progresses and India's major cities are increasingly blanketed with thicker and thicker suffocating smog, it's not surprising that interest in these findings by the senior diabetologist and his fellow researchers is fast growing.

In Mohan and his colleagues' BMJ study, that was funded and monitored by the National Institutes of Health in the US, they have observed a cohort of 12,000 Delhi and Chennai persons from 2010, tabulating their blood sugar levels from time to time, while simultaneously measuring their exposure to air pollution via satellite data and more.

Dr Mohan, who is the chairman of the Madras Diabetes Research Foundation, runs a series of diabetes specialty centres across India and has been working for more than 40 years in diabetes care and research, spoke to Rediff.com's Vaihayasi Pande Daniel about how pollution could trigger the early onset of adult diabetes.

Why and how does air pollution have an effect on blood sugar levels?

Let me step back a little bit: One of the reasons why we checked the (effect of pollution might have on the onset of diabetes) is that we've always known that diabetes rates in urban areas are higher than in rural areas.

Till now, we had an adequate explanation. Urban people are generally well off and so they have a better standard of living. They have vehicles and exercise less.

They generally tend to eat more and tend to eat out and therefore they have more calories, more sugar, more fat, more of everything, more salt, more carbs etc.

Also, the obesity rates are higher. The earning capacity is higher and probably they have more screen time.

There are lots of reasons why urban people can have higher risk for diabetes.

But in addition to all that, there were some reports saying that pollution, particularly particulate matter in the air (of 2.5 micrometres and less), does not just affect the respiratory system.

Obviously, it goes into the lungs and produces coughs, sinus problems, asthma, COPD and even lung cancer. That part we knew. But then systemically also it can affect -- get into the blood and then produce changes.

In an earlier study, from India itself, it was shown that hypertension was much higher and blood pressure was higher when this particulate matter was present, because it leads to inflammation. And inflammation is one of the causes for non-communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension and so on.

What exactly is this study?

In this particular study, which we published in the BMJ (Open Diabetes Research and Care journal), was part of the CARRS or the Cardiovascular Risk Surveillance follow-up study, funded by the National Institutes of Health in the US, and it's being done in Delhi, and then in Chennai.

And not just as one cross-sectional study, but several rounds of cross-sectional studies and also a prospective (future) study -- the same population now we have been following for about 15 years and longer.

It's still going on; the studies have not ended. We're looking at various things like diabetes, hypertension, heart diseases, obesity, lipids, including some cancers which we intend to study.

As part of that, we looked at those who did not have diabetes 10 to 15 years earlier, but have developed a new onset of type two diabetes now.

We were trying to look at various risk factors. Of course, we have also, as part of the geo health studies that we're doing, measured air pollution.

It's much easier to study pollution now and it can be studied using various handheld devices.

We found that even after correcting for all the other factors, like body mass index, or weight, or lack of exercise or overeating, family history of diabetes, income, there was still a correlation with particulate matter levels, that is pollution levels, and new onset of type two diabetes. So that's how the link was established.

IMAGE: Dr Viswanathan Mohan

And how does this actually produce diabetes?

Yes (to answer your question) it does because it acts as an endocrine disruptor.

When it acts as an endocrine disruptor it has an effect on the endocrine system of the human body (which starts with the hypothalamus, pituitary, the thyroid, the pancreas, adrenal, and the glands in the sex organs) and the effect on the pancreas is an important one.

The way you get type two diabetes is due to two defects.

One is the pancreas doesn't produce enough insulin.

The other physiological defect is insulin resistance. Even if insulin is there, it doesn't work in the liver, or in the muscle, and so on.

When you have this particulate matter in the blood, it goes to all the organs, and it promotes inflammation.

The liver gets inflamed, the muscle gets inflamed, adipose tissue gets inflamed, the pancreas gets inflamed.

So, it starts affecting the endocrine system, and that is called an endocrine disruptor.

When it attacks the pancreas, the insulin secretion comes down (reduces), some of the cells may die, the pancreatic cells and the amount of insulin secretion comes down.

Then in the liver, it starts interfering, and insulin doesn't work so well. So, insulin resistance also comes along.

When both these defects occur that actually leads to type two diabetes. So that is our explanation.

Now in an epidemiological study, where we measure this, we can only correct for all the factors.

We cannot actually inject it into the pancreas or use some other method (to demonstrate this).

The explanation or the hypothesis we have is that it's an endocrine disruptor. And it's not just affecting the lungs, but it is affecting other parts of the body and (since) type two diabetes (is setting in) it obviously is affecting the liver as well as the pancreas. Those are two mechanisms by which it brings about type 2 diabetes.

What are the further implications?

As far as the, the applicability of this is concerned, first of all so far, we've been putting all the blame on the individual. 'Oh, that person ate too much'. 'He didn't exercise'. 'They put on weight, obesity, that's the cause'.

Now, of course, all these factors are there (they exist) but there's also a societal element, because the person has been doing all that he can, trying to eat properly, and so on, but because of the pollution is getting into his body, it is producing disease.

How can we protect ourselves?

When you are seeing those pictures (of pollution in Delhi and elsewhere) and there is so much of pollution, it is very obvious, you should wear a mask to protect at least your mouth and nose, and don't allow those toxic substances to go in, like we did during COVID-19.

There are many countries, like South Korea, Japan and Singapore and other places, where they permanently wear a mask.

They believe because of so much of viral disease, plus pollution and everything else, they should wear a mask all the time when they go out into some crowded places and so on. That is one thing that can be done.

What else may we look at?

The second thing is to try to reduce the pollution itself.

We know that in Delhi it's the burning of stubble from Punjab, Haryana and UP that affects. How do we reduce that? How do we make it safer for people to live there?

Obviously, governmental efforts and non-governmental efforts, educating people and finding better ways of preserving the environment is important.

One effort can be made by industries of making their towers (exhaust stacks) so high, so the smoke doesn't come down to where people are and live.

When you have buses, lorries, cars, which are more than four years or five years old, they start emitting smoke.

They go for the PCU test, and then (still) get approval. They must be very strict with that.

They give bribes and the car will continue to pollute (the environment and harm) people.

These are things we are doing for common good, because the health of other people is equally important.

For example, a country like Japan, with so much of civic consciousness, will never allow pollution to go on, because they value the country and their people so much.

In India we have some cities like Indore, for example, which always wins the cleanest city award. They don't allow any trash to be put anywhere. Whenever I go there, I marvel at how proud they are about their city.

Meghalaya too?

Meghalaya yes.

If it's possible in one part of the country, why not in other parts too? If you're able to bring down the pollution, so many manmade diseases can be avoided. This is the first step that you take.

In connection with preventive measures, you have already mentioned about wearing a mask, and societal measures. What else?

Awareness.

Pollution need not be only outdoor pollution. It can also be indoor pollution.

Choolahs (earthen stoves), dhoop, agarbattis?

Exactly, exactly.

Choolahs, agarbattis, also firewood being used in the kitchen and coal.

If it is a small house with only a small kitchen, a closed place with no ventilation, you can imagine how much will be getting into the body in such circumstances.

Smoking. Passive smoking, as well as active smoking.

Can burning scented candles contribute?

They can be. If it's a small room. They all add on because all particulate matter will come in the smoke.

Mosquito coils?

We have to study it. Probably have to collaborate with lung specialists to find out what particulate matter it exactly contains.

Anything which is unusual and is adding to the particulate matter in a place, you have to view with caution. They can all add on.

If you live in a city which has got a lot of pollution, it's very hard to control your environment. And who knows when the government is going to get around to controlling the air pollution levels. Supposing you do have a genetic risk of diabetes, do you have to work even harder at your diet and your physical exercise regime because you live in a polluted place?

Obviously, if there is family history of diabetes, you're overweight, you're eating the wrong stuff, you're not exercising, you have already pushed yourself -- the risk has already increased a lot.

In these individuals, the exposure to pollution may be just that little trigger sufficient to bring on the onset of diabetes.

Whereas if you're thin, have no family history of diabetes, you're exercising and you're eating the right stuff, maybe your body is able to tolerate that amount of pollution. Or it may produce some other disease but may not produce diabetes.

There are accumulative aspects to risk factors. For example, if you have no family history at all, your risk it goes down by about like 50 per cent.

But if your father had diabetes and your mother had it and your grandfather had it, and everybody had it, all you need is being overweight by two kilos. That is probably enough to push you into becoming diabetic.

But if you don't have family history, you might have to become 20 kilos overweight to develop diabetes.

If you have all those risk factors, then even a little bit of pollution is probably enough to trigger diabetes.

So, to answer your question, yes, you need to work harder, if you have those risk factors and if you also have pollution.

Wearing a mask is critical and avoiding very, very, crowded polluted places if you can avoid them.

- Part 2 of the Interview: 'Air pollution can lead to cancer'

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025