'In any institution that has a passionate ideology, the moderate is always vulnerable to the person who is more extreme, because that is what the supporters want.'

'This was the natural culmination of the sort of movement that Vajpayee and Advani began, and though Vajpayee probably did not understand it, Naipaul certainly did,' says Aakar Patel, winner of the 2018 Prem Bhatia Award for Political Reporting.

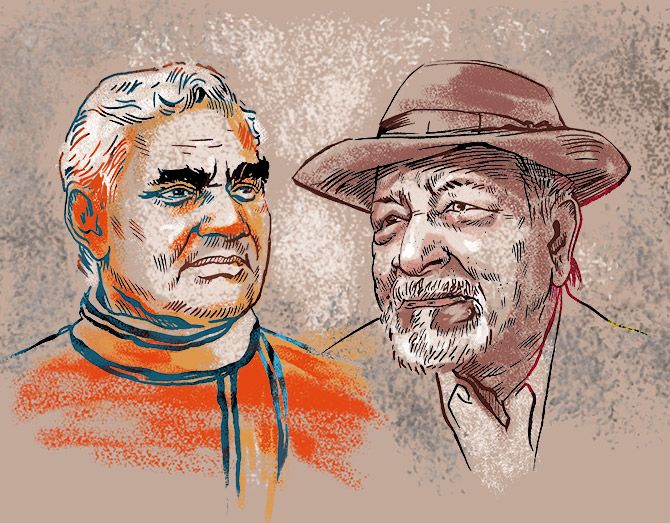

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

Two famous men have died and many things have been written about them. It is our tradition in India -- and also generally speaking around the world -- to only say good things about the dead.

But no man is perfect and we owe it to ourselves to be honest.

In that spirit let's have a look at some of the aspects of these two who have departed. The more interesting of them was the writer V S Naipaul.

His first name was Vidiadhar and he came from Trinidad, a place Indians know because of Indian origin cricketers like Sunil Narine and Denesh Ramdine.

The Bihari ancestors of these people had moved about 150 years ago as contracted slaves for a limited period (called 'bonded labour') to what we call the West Indies, to work on sugar plantations. But after their fixed term slavery ended, they did not have enough money to return home and remained there, developing their own Indo-Caribbean culture.

Naipaul spoke no Indian language but knew Spanish and English. He knew that the root of his first name, Vidia, was the same as the Latin and English word video (which means 'I see').

He studied at Oxford on a scholarship and then worked for the BBC in London. In his 20s he began writing a series of novels and travel books. In these he examined cultures and their differences and their flaws.

He had exceptional abilities of observation, and was able to penetrate quite deeply into something just by looking at it.

For example, he went to Iran and immediately saw that the black robes and headdress that was worn by the Shia clerics was the origin of the black Oxford and Cambridge graduation gown, which today is common across the world.

Naipaul wrote that Indians did not have this power of observation. Indians who travelled abroad were like villagers who were unable to notice the differences between their own culture and what they saw abroad, particularly in the West.

They were blind in many ways to the world. He developed this thesis of Indians being flawed later in life.

When he came to India in the 1960s he was puzzled by why it was so dirty and inefficient. His first book on India, An Area of Darkness, was a record of how bad most things in India were.

He was shocked by what he saw because, he said, his parents and relatives had spun the story of India being some sort of wonderland. He said that An Area of Darkness was for him not an easy book to write.

Naipaul was disliked by almost everyone in India who had read his book (not many have) or were familiar with what he said because of media reports. This was the more common way in which people knew of this writer's existence.

Another of Naipaul's allegations against Indians is that we do not read. He claimed most Indians have not read either Gandhi's autobiography or Nehru's though they have strong views on both men.

The Bombay poet Nissim Ezekiel read An Area of Darkness and wrote a response called Naipaul's India And Mine.

Still later Naipaul further developed his thesis. He concluded that Hindus were blind and inward looking and unable to observe anything because they had been colonised intellectually by centuries of Islamic rule.

He felt that the movement against the Babri Masjid was a positive one and that good things would come of the destruction of the mosque. The violence would in some ways lift the Hindu spirit and make it more alive.

For saying this, again he was disliked by many in India. It is true that he was not able to support this with any evidence, even observational evidence. It was just what he felt.

Now let us turn to the second famous man who left us, former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. He is seen today as a gentle man who was different from the rest of his party in many ways. This is his standout feature.

Vajpayee is liked by people across the political spectrum because though he was from the school of culture and politics that targeted minorities, he was seen as a moderate.

Under him, the BJP's three main political issues were taking over the Babri Masjid, removing the Constitutional autonomy of Jammu and Kashmir and removing the personal law of India's Muslims.

He pushed for all of these three vigorously and in partnership with L K Advani, he was able to introduce powerful religion-based sentiments into our politics, which had been absent at the national level for the first four decades.

The BJP was richly rewarded for this, and it owes its development as our main political party to this action by Vajpayee and Advani.

Vajpayee was ideological, in the sense that he genuinely believed in Hindutva, but he did not like extremism or violence. This is what made him a misfit in his party, which was essentially enthusiastic about street action, like Naipaul wanted it to be.

The reason we did not have things like gau rakshak violence in the first NDA government was because of this duality of Vajpayee. He wanted to protect the cow, but he was not comfortable with the street violence this sentiment produced.

This contradiction made Vajpayee liked and people like George Fernandes and Mamata Banerjee joined his government.

The problem of such a position was revealed in 2002 when Vajpayee tried to remove the chief minister of Gujarat, but the karyakartas did not allow him.

In any institution that has a passionate ideology, the moderate is always vulnerable to the person who is more extreme, because that is what the supporters want.

This was the natural culmination of the sort of movement that Vajpayee and Advani began, and though Vajpayee probably did not understand it, Naipaul certainly did.

Aakar Patel is Executive Director, Amnesty International India. The views expressed here are his own.

- You can read Aakar's earlier columns here.

© 2025

© 2025