Both have been robustly muscular leaders who began as immensely charismatic politicians conveying an impression that they were makers of history, raring to go.

Both have been hyperactive on the world stage.

But Abe is departing on a somber note, unceremoniously and apologetically, observes Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar.

The earth becomes a lonely planet for Prime Minister Narendra Modi as his friend and Japanese counterpart Abe Shinzo announced his resignation from office on August 28 and began walking toward the sunset. Abe should have been around on the stage until September next year at least.

Modi wasn't exaggerating when he said he was "pained" to hear the news from Tokyo.

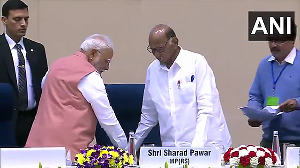

Modi had a warm friendship with Abe and India-Japan relations have never looked so good as today.

Modi and Abe have been master performers on the Asian stage in making India-Japan relationship look larger than life. It isn't easy to inject swagger into a relationship that lacks substantive content, but Modi and Abe somehow managed to do that.

However, Abe has been far less successful when it came to his own legacy.

Not everyone gets a brand of economics named after him.

But, was 'Abenomics' a success? Abe inherited an economy that had pretty much flattened by the 1990s.

There was very little growth, and Abe tried an unorthodox way to liven things up by creating a small bit of inflation through fiscal stimulus and other structural reforms so that people began investing and there'd be renewed growth.

But the end result has been very mixed.

The pumping of stimulus caused debt-to-GDP ratio shoot up dramatically to 250% which is astronomical. (Even Greece at the height of its crisis only touched 180%.)

Another key policy Abe wanted to push through was the revision of Japan's pacifist constitution.

Article 9 of the constitution renounces war; Abe wanted to change it so that Japan's self-defence forces could be recognised as an army and can be deployed overseas.

That plan hasn't gone through.

Abe tried hard to create political conditions for his project to be acceptable to the nation so that it could get popular support, but he ran into headwind, as the initiative got stuck in the special parliamentary committee, given the opposition's 'filibustering' to kill time.

Abe could sense that his ideology-driven nationalist aged was slipping and the country wasn't ready for it.

Nonetheless, he managed to get some changes though in defence policies such as on collective self-defence or export of military technology.

Abe's ambition was to retire in triumph presiding over a buoyant economy, a new constitution and the staging of 2020 Olympics.

But as fate would have it, the pandemic appeared out of nowhere and put paid to all that.

Abe hoped to showcase the relaunch of brand Japan at the 2020 Olympics. Japan's biggest companies invested a lot of money into it, but even if the pandemic were to subside by next summer, Japan would be hosting probably a much smaller Olympics, which will be a blow to the country's economy.

Abe's popular support wilted over his handling of the pandemic.

In a poll in early August, his approval rating had dropped to 32.7%. Abe's initial slow response to the pandemic and thereafter his misjudgement in striking the balance between 'shutdown' and the reopening of the economy, low levels of COVID-19 testing, his slowness over stimulus payments -- in all this he came out as a leader with faltering grip on things.

Added to that was Abe's aloofness, passing on the buck to his cabinet colleagues, which created a perception that he was deliberately trying to avoid personal accountability as prime minister on a critical issue for the nation.

This has been an important factor undermining his popular support.

At the same time, there were the scandals and cronyism, and Abe's failure to provide convincing accounts of his behaviour.

The Moritomo Gakuen and Kake Gakuen scandals prompted allegations Abe showered favours to friends and associates, involving charges of political cover-up and doctoring of public documents.

The annual cherry-blossom-viewing party was extravagantly lavish last year and when the Opposition started asking questions, the cabinet office shredded the documents listing attendees, in violation of government rules.

Indeed, Abe has had a lot of explaining to do on these and other scandals to the Diet, the Japanese parliament, the media, and the public.

In foreign policies, Abe was very much an outward-oriented prime minister.

Abe's main accomplishment is that he re-established Japan's own identity in the international arena as an old democracy and as a maritime nation.

His brand of identity politics in diplomacy brought Japan close to India and Australia in the Asia-Pacific and, of course, he strengthened Japan's alliance with the US.

Abe has achieved remarkable results in strengthening Japan-US relations.

In fact, Japan-US relationship has become the cornerstone of Tokyo's foreign policy, and Abe himself became one of US President Donald J Trump's few best friends.

Having said that, Abe could not dissuade Trump from abandoning the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement, which for Abe was much more than an alternative de-Sinicised industrial and supply chain for trade and investment, but was at the very heart and soul of his containment drive against China.

To be sure, Abe embraced the US Indo-Pacific Strategy and deepened the military cooperation with America.

On the other hand, this should not detract from Abe's geopolitical balancing skills in not picking a side between China and the US, either.

In the post-Abe transition, Washington will be watching with unease Japan's pursuit of strategic flexibility and autonomy in military deployment, although the fundamentals of the US-Japan alliance will remain strong.

It is no small matter that he was remarkably successful in calming tensions with China over the disputed islands in the East China Sea.

But the two causes dear to Abe were the restoration of Japanese sovereignty over the Russian-held Northern Territories and the return of Japanese abductees from North Korea -- and he failed to achieve both.

In the final reckoning, the final impression is unavoidable -- Abe leaves a Japan all dressed up and nowhere to go.

Modi has a few useful lessons to draw out of Abe's legacy.

Both have been robustly muscular leaders who began as immensely charismatic politicians conveying an impression that they were makers of history, raring to go.

Both have been hyperactive on the world stage.

But in the final analysis, Abe is departing on a sombre note, unceremoniously and apologetically.

He leaves quite a few unfinished agenda. The things Abe set out to do as priorities have not been a success, but his legacy as Japan's longest serving prime minister remains difficult to beat.

The noted Australian academic Professor Aurelia George Mulgan wrote about Abe, 'The tide of history had turned against Abe; he ran out of time and became a prime minister without a cause he could deliver.'

Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar served the Indian Foreign Service for more than 29 years.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025