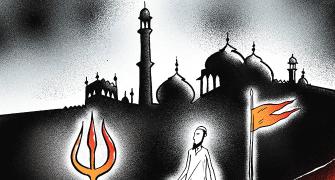

'Nitish is now a helpless junior ally of Hindutva.'

'He just cannot think of reining in the hoodlums raging, marauding and killing in the mohallas,' argues Mohammad Sajjad.

IMAGE: Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, flanked by Deputy CM Sushil Kumar Modi and assembly Speaker Vijay Chaudhary, leads a human chain against child marriage and dowry in Patna, January 21, 2017. Photograph: PTI Photo

Bihar, and many parts of West Bengal, close to Bihar, has been engulfed in communal tension and violence.

Religious processions (Ramnavmi and Chaiti Durga; in late January it was Saraswati Puja) carrying illegal weapons, entering Muslim mohallas, shouting incendiary slogans, ransacking masjids and madrasas (at Rosera in Samastipur) were the order of the day in the last few days.

So much so that Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar is not able to prevent it even in Silao (Nalanda), his home district.

The Opposition Rashtriya Janata Dal, despite its huge cadre base, on the other hand, is hardly doing anything proactively to confront the menace.

Despite the Godhra train carnage and subsequent massacres of 2002 in Gujarat, Nitish, then the Union railways minister, chose to continue in alliance with the ruling BJP.

It should therefore not surprise anyone that Nitish is sort of choosing to fail to rein in the hoodlums raging across Bihar. But it does surprise many! Why?

Because:

- a. Nitish governed Bihar between 2005 and 2013 in alliance with the BJP when the BJP was not in power at the Centre. Then, he was the dominant ally, keeping the Hindutva agenda at bay, with various other exercises of social coalitions -- Ati Pichhra, Mahadalit, Pasmanda and women empowerment.

- b. Indian electorates arguably have strange ways! Are they too generous in giving the benefit of doubt to their leaders -- political, as well as religious? Nitish pulled out of the Mahagathbandhan with the RJD and Congress in July 2017 for reasons best known to him.

Speculation suggests that:

- a. Nitish re-aligned with the BJP to avoid the discomfiture to be inflicted upon him in the Srijan scam case and other such cases pending, or to come up, against him.

- b. Nitish was not comfortable with the ever-growing demands of the Yadavas and that by the next elections, Tejaswi could anyway have tried to replace him, given the fact that his core support base, the Yadavas (12%), are numerically far ahead of the Kurmis (4%), to which Nitish belongs; and given the fact that Muslims (17%) have always trusted Lalu, rather than Nitish, makes the RJD's base far more stronger. Nitish did test it in the 2014 election that Muslims could not trust him;

- c. If an ndtv.com report (Manish Kumar, December 4, 2017) is to be believed, Lalu and his Man Friday, Prem Gupta, approached Arun Jaitley, the Union finance minister, asking for some reprieve in corruption investigations and that as a quid pro quo Lalu would kick out Nitish within 24 hours. As it leaked out to Nitish, he brought an end to Bihar's Mahagathbandhan.

Be that as it may, it did not require great intelligence to guess and foresee that Nitish's realignment with the BJP in 2017 was not going to keep him as a dominant partner within the National Democratic Alliance unlike what he really had been between 2005 and 2013.

His credibility and trustworthiness among the electorate, as well as among the allies, on both sides of the divide, have dipped low because of opportunistic hoppings.

In this situation, it was anticipated that the fiercely and unprecedentedly ascendant saffron outfits would outsmart and marginalise him.

The spurt in the communal clashes in Bihar after June 2013 (when Nitish pulled out of the NDA), and its further resurgence since July 2017, when Nitish re-joined the NDA, after the BJP formed the government in Uttar Pradesh, and the proliferation of various saffron outfits, including the Hindu Yuva Vahini -- spreading from its headquarters in Gorakhpur (UP) to the adjacent Saran (Bihar) -- is exactly on predictable lines, at least for Bihar watchers.

Precisely because of this, Nitish is now a helpless junior ally of Hindutva.

He just cannot even think of reining in the hoodlums raging, marauding and killing in the mohallas.

He cannot do what Mamata Banerjee is doing. Her police is seen directly confronting with the marauders.

Senior bureaucrats claim that Nitish's higher bureaucracy is cozying up with his dominant partner for more remunerative central assignments.

They are therefore no longer cooperating with him in maintaining law and order and in preventing the armed processions shouting provocative slogans by forcefully entering Muslim mohallas.

True, Nitish did succeed in penalising the rioters of the Bhagalpur massacre (1989-1990). But now even if he wished to rein in the rioters, he can no longer do anything.

His ally, now a dominant one, cannot allow him to do so.

The card of Hindutva, as an electoral saviour of the incumbent regime, is being played out in utter desperation.

IMAGE: Samajwadi Party workers rejoice after the party shocked the BJP in the Lok Sabha by-elections in Gorakhpur and Phulpur. Photograph: PTI Photo

It appears that the victory of the Samajwadi Party-Bahujan Samaj Party alliance in the Lok Sabha by-elections in Gorakhpur and Phulpur has created anxiety in the saffron camp. Particularly, because Gorakhpur, the UP chief minister's bastion, was wrested away by a subaltern community of fishermen (Nishads/Mallahs).

This specific community has been organising itself and asserting itself politically in parts of eastern UP and northern Bihar.

The Mallahs (Hindu fishermen, including allied/similar sub-castes like Gangotas and Kevats -- the boatmen -- those earning their livelihood by river water) are now emerging as the 'Dominant Castes' in these parts.

The rise of the Mallahs in Muzaffarpur (Bihar) since the 1990s almost sealed the prospect of a Bhumihar being elected from the Muzaffarpur Lok Sabha seat. The Bhagalpur Lok Sabha seat is represented by an RJD MP who belongs to Gangota community.

Similar fear of the Rajputs is emerging about Gorakhpur. The Nishads have also staked their claims on Yogi Adityanath's Gorakhnath Math.

IMAGE: RJD Supremo Lalu Prasad Yadav with his daughter Misa Bharti and sons Tej Pratap and Tejashwi Yadav. The RJD ruled Bihar from 1990 to 2005. Photograph: PTI Photo

It has to be understood that Bihar and Uttar Pradesh had long spells of Backward and Dalit rule since 1989-1990, against which the spell of Hindutva sort of crashed despite such mobilisation in the Ram Janambhoomi's name in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Thus, the ideological bulwark of 'social justice' kept Hindutva on hold.

Had these two provinces been a Congress stronghold after 1989-1990, these provinces too could possibly have fallen to Hindutva just as they did in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and also in Rajasthan to a large extent, besides Maharashtra and Gujarat, where Congress rule did not offer any ideological counterpoint to Hindutva.

Additionally, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra have relatively lesser proportion of Muslims. These provinces therefore, arguably, offer now relatively less incentives to Hindutva mobilisation as years of such activities in these provinces seem to have reached saturation by now.

In Bihar and UP, Muslims have a sizeable number and a corresponding public profile. It therefore offers a fertile ground for the kind of polarising agenda, now when the supremos of the Backward and Dalit political parties have become single caste monopolies with meteoric rise in the political and economic fortunes of the supremos and their kin.

As against it, ascendant Hindutva offers some sort of political career 'open to talent'. For such aspirational youth, communal activities are exercises in political CV building.

Jobless youth therefore join in for money, a piece of action, and for political rise. Under friendly regimes, there is a renewed push to consolidate and expand to new grounds.

This further explains why there is a sudden spurt in communal tension and violence in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

One may see some pattern in the recent violent communal onslaught in Bihar.

The geography of the violence suggests that those places are more prone to such violence, where:

- i. Either the BJP's allies are likely to stake their claim to Lok Sabha seats in 2019, or

- ii. Incumbent BJP MPs feel insecurity due to the discontent of certain caste groups which may desert the BJP:

- a. Munger (where Lalan Singh, a close aide of Nitish, is supposed to be an important leader);

- b. Rosera (Samastipur), which was once represented by Ram Vilas Paswan, has a sizeable Kurmi, Koeri and Dalit population. Besides, Rosera town has a significant presence of Muslim traders; the incumbent Samastipur MLA is a Muslim, Akhtarul Islam Shaheen of the RJD;

- c. Jamui (currently represented by Chirag Paswan, Ram Vilas Paswan's son);

- d. Aurangabad (represented by the JD-U in 2009; its nominee Sushil Kumar Singh is now in the BJP, and the incumbent MP);

- e. Silao (Nalanda, Nitish's home turf);

- f. Bhagalpur (which has been Ashwini Chaubey's preferred choice to contest from; violence broke out here after Ashwini's son Arijit Chaubey allegedly led a mob, and even mocked at the FIR lodged against him);

- g. Siwan (from where the JD-U would like to contest);

Violence broke out in:

- a. Marwan (Muzaffarpur, Vaishali Lok Sabha seat), which is currently represented by the LJP;

- b. Aba Bakrpur, Mahuwa (Hajipur Lok Sabha seat), represented by Ram Vilas Paswan;

- c. Dhaka (Champaran, Motihari Lok Sabha seat), which is represented by Union Agriculture Minister Radha Mohan Singh who has to feel irate farmers;

- d. Gaya's incumbent BJP MP Hari Manjhi feels insecure after Jitan Manjhi went over to the RJD;

- e. Nawada, represented by the BJP's Giriraj Singh who keeps issuing polarising statements. This was, till 2014, supposed to be a safe seat for the JD-U, and has also witnessed intra Yadav rivalries. The JD-U's Kaushal Yadav (his wife Purnima Yadav is the Congress MLA from Gobindpur, Nawada) and the RJD's Rajballabh Yadav compete with each other.

With more intensified communal polarisation, the BJP may be trying to torpedo the emerging alliances of backwards and Dalits. That may explain the renewed spurt and virulence in communal skirmishes since late March.

The BJP's rising desperation has also got to do with the fact that smaller allies representing specific subordinated castes (Upendra Kushwaha's RLSP, Ram Vilas Paswan's LJP, and the BJP's other such allies in UP), have not been able to strengthen their base, despite being in alliance with the ruling BJP.

Immediately after the UP by-poll results, some allies -- including Ram Vilas Paswan -- vented their discomfiture against the BJP. All this dissent is being sought to be made ineffective by consolidating the Hindus, behind the BJP, through intensified communal polarisation.

In this scenario, it seems almost inevitable that Nitish would increasingly be cornered into political oblivion.

Even if he would merge with the BJP, he may not remain on the top any longer.

Meanwhile, Bihar keeps sliding on all fronts, for which Nitish cannot deny a considerable share of blame.

The Opposition is not mobilising its cadres to confront the hoodlums head on. RJD cadres do not seem to pursue a politics of direct, on-the-street, intervention nor is it resorting to legal battles in each case of rioting, to rein in the hoodlums.

Secondly, Tejaswi Yadav -- Leader of the Opposition in the Bihar assembly -- does not seem to be sincere about propping up leaders from non-Yadav OBCs and Dalits who had deserted the RJD primarily because of the Yadav hegemony.

Other secularists and liberals are, for instance, not able to ask even the Muslim clergy NOT to bring out huge processions in several towns on a misogynist issue.

They erred in 1986 when they upturned the justice dispensed to Shah Bano through Parliamentary legislation, giving rise to majoritarian reaction.

They are repeating that mistake again. Yet many of the liberal-Left intelligentsia, and 'Muslim-friendly' regional formations, are hardly speaking out against them sternly, giving some sort of credence to the Hindutva canard of Muslim appeasement.

This is what has been corroding their credibility during these many decades, giving rise to the menace of majoritarianism. The point is simple. Caste and gender based regressivism/conservatism and communalism have a cause-effect relationship.

The need of the hour is to frankly accept past mistakes, to regain the people's trust.

Only then will secular progressive forces be able to convince the electorate while exposing the failures of the incumbent regime on all fronts, and to expose them as to why they have resorted to poisoning society and the body politic with fear and hatred.

Mere opportunistic stitching of coalitions will not convince the electorate that such an arrangement will really sustain itself and deliver on economy and employment.

Professor Mohammad Sajjad is at the Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University, and is author of Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours (Routledge 2014/2018 reprint).