In the mid-1980s, India and the US struggled to arrive at sufficient confidence for Washington to even sell a supercomputer to India for monsoon prospecting.

Now, the most sensitive military technologies, data, and intelligence resources are being shared.

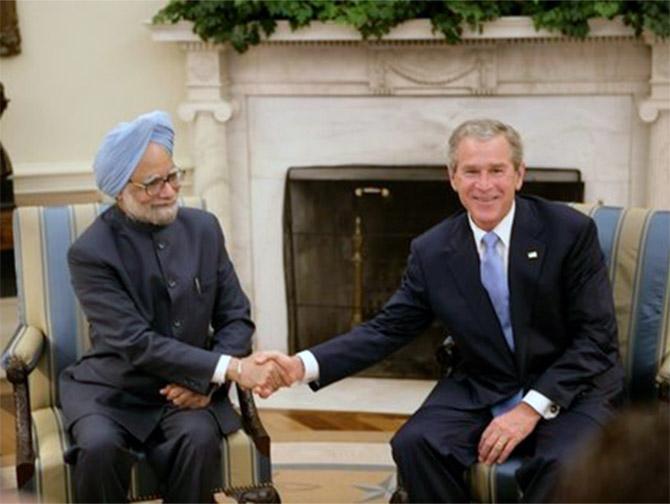

This would not have happened without that one big deal that changed the fundamentals of India-US relations, notes Shekhar Gupta.

In the first 53 years of our independence, only three US presidents visited India: Dwight Eisenhower (1959), Richard Nixon (1969), and Jimmy Carter (1978).

Donald Trump's was the fifth presidential visit in the past 20 years.

Two big nations that remained at strategic odds for half a century are making up for lost time.

The end of the Cold War and the Soviet bloc coincided with the Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh economic reforms and the 25 years of Indian growth.

A fresh opening up between India and the US was natural.

But, if you were asked to name one fact or achievement that characterises this turnaround most of all, what would it be?

I'd say, it's the India-US nuclear deal.

I know it will draw two extreme reactions.

One, so what is the big deal, everyone knows it.

And at the other end, ha ha, big deal! Not one megawatt of nuclear power has been installed since, and an American reactor won't be producing any for the next 15 years, if ever.

To think that the India-US nuclear deal was either about a bilateral relationship or energy is to miss the point.

The degree of difficulty that Dr Singh faced in making it a reality underlines how complex it was and what wide-ranging implications it had.

Let us list six here.

The first and the biggest implication of the deal was ideological.

It was the first time that India had signed a treaty of any kind bilaterally with the Americans, with high strategic implication.

Not only did it mark a 180 (if not 360) degree repositioning of India in the post-Cold War world, it also tested our public opinion on a vital question: Would it trust Americans to be friends after decades of suspicion?

To that extent, it ran contrary to the ideological nationalism the Congress and its Left intellectual vanguard had built so masterfully.

That is why it ran into immediate opposition from the Left, but also almost the entire Congress establishment.

Besides, there was the usual nonsense, like Muslims will be upset.

Because Dr Singh decided to make this the touchstone of his prime ministership and threw into the battle all his carefully conserved political capital, he pretty much arm-twisted a reluctant Sonia Gandhi into agreeing, even as her old guard turned up its nose.

The general election that followed, in 2009, proved that the Indian voter was smarter, a better judge of the national interest, and enormously more honest than the old Left and, frankly, even the Right.

The BJP, usually seen as pro-West through India's decades of Soviet enchantment, opposed the deal even more strongly on nationalist grounds than the Left did ideologically.

Both were defeated.

The UPA returned in larger numbers and the ideological ghost of anti-Americanism was buried so deep that you do not see it being exhumed.

The post-Cold War India was born.

The second gain was of strategic principle

Although Montek Singh Ahluwalia, who was deputy chairman of the planning commission, talking to me about his latest book, Backstage, put it at the top of his list.

He said Dr Singh was deeply concerned about India having been subjected to nuclear apartheid as, despite being a declared nuclear weapons power, it wasn't treated as one for nuclear commerce and technology transfer/exchange regimes because of the old, discriminatory regimes originating from the discriminatory Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The nuclear deal gave India the opportunity to break out.

It was also a fortuitous period when the US president had greater leverage with his Chinese counterpart and could lean on him to ease up on India.

India is now accepted as a nuclear weapons power, more or less like any other under the NPT, but also respected as a responsible, non-proliferating one, unlike rival Pakistan.

The third is of great domestic significance.

Until now, there was no compulsion on India to subject itself to accepted international safeguards and standards of transparency.

Because civilian and nuclear programmes were mixed up, and deliberately so, to ensure one masked the other.

There was zero transparency and oversight. This included Parliament.

At the same time, because civil and military were mixed up, nuclear scientists in Indian labs struggled to excel in a free, international peer-reviewed environment as everything was seen as covert and suspect.

One big gain of the nuclear deal therefore was to bring India's nuclear programme, including its funding and performance, into a more transparent domain.

It also brought more installations, declared civilian, under international safeguards.

Overall, it promoted more responsible behaviour, accountability, and safety.

The benefits in the tactical, military, and scientific fields come next.

It may have been called a 'civilian' deal, but in essence it was deeply military and strategic.

It resulted in a rapid relaxation of the US establishment's old fears of transferring sensitive military technologies and equipment to India.

In the mid-1980s, India and the US struggled to arrive at sufficient confidence for Washington to even sell a supercomputer to India for monsoon prospecting.

This, despite a fine personal equation between Rajiv Gandhi and Ronald Reagan.

Now, the most sensitive military technologies, data, and intelligence resources are being shared.

This would not have happened without that one, big deal that changed the fundamentals of India-US relations.

The fifth gain is the context of regional geopolitics.

For 15 years since the Cold War ended, America had moved gingerly towards de-hyphenating its India policy from Pakistan.

The nuclear deal changed all that dramatically.

For the first time, Washington had signed a strategic deal with India which wasn't -- and has still not been -- offered to Pakistan.

If you do not see it as the final striking out of that dreaded hyphen, ask a Pakistani strategist.

Since then, the Americans have done very little to bring it back.

It is just that we Indians, especially under the Modi government, keep relapsing into that trap, given how undeservingly important Pakistan is made out to be in our internal politics.

The sixth and the last, and I say so with trepidation, is my favourite.

It is a gain of immeasurable significance in our domestic politics.

The nuclear deal, and the way our political Left went out on a limb to fight it, and lost, ended a scourge of our political economy: The Left.

In 2008, it owned the central government with 60-plus seats.

Now, it struggles to get into double figures in the Lok Sabha.

It made common cause with the BJP in Parliament to bring down Dr Singh's government, and was defeated.

It exposed both, the Left's ideological bull-headedness (blind anti-Americanism) and hypocrisy (joining hands with political Hindutva).

Soon enough, it was routed in West Bengal, as if forever.

That's a gain to keep for generations.

So what if it took a little bit of the foreign (American) hand to achieve this.

By special arrangement with The Print

© 2025

© 2025