Can you find a world leader who has met generations of Indian politicians, most US Presidents, European head of States, several Popes, celebrated cricketers, Hollywood and Bollywood stars, some of the greatest scientists and many ordinary people, including what he calls, 'Chinese brothers and sisters?'

Can you find a world leader who has met generations of Indian politicians, most US Presidents, European head of States, several Popes, celebrated cricketers, Hollywood and Bollywood stars, some of the greatest scientists and many ordinary people, including what he calls, 'Chinese brothers and sisters?'

Claude Arpi salutes His Holiness the Dalai Lama as he turns 80.

Nothing speaks more about the Dalai Lama's predicament than his recent visit to the UK. WantChinaTimes, a Taiwanese publication, reported rumours in the Chinese media: Chinese President Xi Jinping's UK visit scheduled for October may be cancelled or delayed as an echo of an earlier controversy in which British Prime Minister David Cameron was forced to delay a planned trip to China.

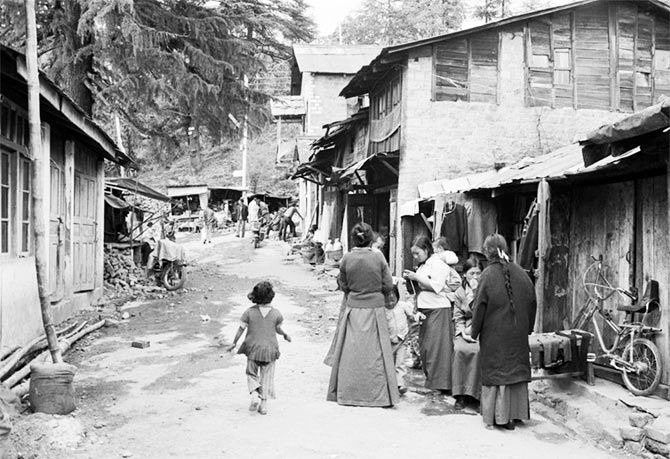

Image: The Dalai Lama (with umbrella) during a visit to the School of Buddhist Dialectics in Dharamsala in 1972. Courtesy, Claude Arpi.

In May 2012, Cameron had dared to receive the exiled Tibetan leader in London.

The Taiwanese Web site explains: 'The Chinese government is vehemently opposed to the religious leader's political and religious authority; it cannot tolerate any challenge to its power.'

This time, the Dalai Lama did not meet any British political leaders. London was not ready to spoil the grand reception planned for the Chinese president later in the year.

The other side of the coin is that the Dalai Lama received an ovation at the Glastonbury music festival, where he spent an hour telling the large crowd of tens of thousands waiting under the rain, how the world could be a happier place if human beings were more compassionate.

The Tibetan leader also called for a more 'holistic education' which should bring 'a sense of care and human love.' To the delight of the festival-goers, he asserted, 'Everyone has the right to achieve a happy life.'

The crowd wished him, 'Happy Birthday' for his 80th year; he responded by asking everyone 'to think seriously about how to create a happy world.'

On one side, you have London's changed attitude towards the Dalai Lama, mainly due to the heavy (economic and political) price paid earlier, and on the other side tens of thousands of 'common men,' cheering one of the most charismatic leaders of the planet, a man who speaks of human values such as compassion, non-violence and the oneness of humanity.

What can one conclude, except that there is a serious widening gap between the political leadership (anywhere in the world) and ordinary citizens.

My first encounter

This reminds me of the first time I met the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate (of course, at that time, there was no question of a Nobel Prize).

It was in 1972, at the hill station of Dharamsala, where the Dalai Lama had been relocated by the Government of India after his flight from Tibet in 1959.

The Lama was truly a 'simple' monk. I remember him, walking from his 'Palace' to the School of Buddhist Dialectics to check on the ongoing construction. He was accompanied by one or two attendants and a security officer. No advance notice, no heavy security, just a smiling monk, looking after the rehabilitation of his people, particularly his monks.

Everyone could approach him and bow down to receive his blessings. Over the years, his popularity increased. He still smiles, but he is now under Z+ security cover, making him more difficult to approach.

In 1974, I was at Geneva airport when he landed in Europe for the first time; here too, no special fuss over the monk. Switzerland had been the first country to grant him a visa, despite Beijing's protests. Over the years, China's muscle power grew stronger, so did the Chinese 'orders.'

Sometimes, I am nostalgic of those old days, when he was so approachable, though he did not have the world dimension he has today.

An exceptional fate!

He is born 80 years ago in a remote village of Amdo province, not far from the border with China (today's Qinghai province). In his village, most of the twenty-odd families made a 'precarious living', he wrote years later in his autobiography, Freedom in Exile.

He also remembered: '(one) favourite occupation of mine as an infant was to pack things in a bag as if I was about to go on a long journey. I'm going to Lhasa, I'm going to Lhasa, I would say. This, coupled with my insistence that I be allowed always to sit at the head of the table, was later said to be an indication that I must have known that I was destined for greater things.'

What a fate! Can you find today, a world leader who has met Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Jawaharlal Nehru, 3 or 4 generations of Indian politicians, most US Presidents, European head of States, several Popes, celebrated cricketers (though he told me one day that he did not understand the game), Hollywood and Bollywood stars, some of the greatest scientists of our time and many, many ordinary people, including what he calls, 'Chinese brothers and sisters'?

What makes the Dalai Lama different?

Apart from possessing extraordinary charisma, why does the Dalai Lama matter so much in today's world?

The first thing which strikes someone meeting the Tibetan leader is his lack of pretence. A couple of years ago in Ahmedabad, I remember attending a function at the Indian Institute of Management. The chairman of the prestigious institution introduced the chief guest as 'a living Buddha.'

The Dalai Lama hammered home several times, 'I am not a living Buddha, I am just a monk.' And for the audience of future CEOs, he added, 'A Marxist monk, but a true Marxist, not like in China!' This remark is obviously not appreciated everywhere.

His Three Commitments

Several years ago, he declared that he had three commitments in this life.

The first is -- 'the promotion of human values such as compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, contentment and self-discipline.'

He likes to speak of 'human values as secular ethics.' After more than 50 years in exile from his native land, he continues to share these human values wherever he travels.

What is exceptional about the Dalai Lama is that he is able to place 'humanity' before his own self; before his own community and even his own nation.

For his second commitment is not Tibet, he works for 'the promotion of religious harmony and understanding among the world's major religious traditions.'

He strongly believes that 'despite philosophical differences, all major world religions have the same potential to create good human beings.'

Are there many religious leaders in today's world who are ready to admit: 'Several truths, several religions are necessary?'

He often makes a difference between Buddhist science, Buddhist philosophy and Buddhist religion: 'It is important to understand that when I say "Buddhist science," I mean science of the mind; it is something universal; it is not a religion. Buddhist religion is not universal, it is only for Buddhists,' he points out.

And for the past 30 years, he has been meeting Western scientists to exchange views on the Buddhist science of the mind.

And where is his Land of Snows in all this?

It is his third commitment; he says: As a Tibetan (who) carries the name of the 'Dalai Lama,' Tibetans place their trust in me. Therefore, (my) third commitment is to the Tibetan issue.'

Unfortunately, for the past 50 years, no progress has been made on this third issue.

The Dalai Lama and India

He often tells Indian audiences: 'I consider Indians as my gurus, because we follow the Nalanda tradition. All our concepts and way of thinking comes from the Nalanda Masters. Therefore, we are the chelas and Indians are our gurus.'

This deeply infuriates the Chinese leadership. A recent article on the official Chinese Communist Party Web site, says: 'After the rebellion in 1959, the Dalai Lama fled the country. What is more ridiculous is that recently he called himself a "son of India", even though he still has Chinese nationality.'

Well, the Dalai Lama believes that he belongs to humanity, not to any particular country.

At the same time, it is a fact that today China has become so powerful that most heads of State or government, like Mr Cameron, think twice before receiving the 'simple monk'.

Take all the Buddhist countries around India -- Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Burma, Nepal or Thailand -- nobody dares to invite the Tibetan leader, fearing Chinese wrath. It is a telling point about the state of the world and its values today.

The Last Dalai Lama

The 14th Dalai Lama will be remembered for a most extraordinary decision: He may terminate the lineage of the Dalai Lamas.

In December 2014, the Buddhist leader told the BBC that it 'would be better that the centuries-old tradition (of having a Dalai Lama) ceased at the time of a popular Dalai Lama.'

He hinted that a Dalai Lama 'found' by China could be extremely unpopular with the Tibetan people.

The present Dalai Lama knows that the Rule by Incarnation, in other words, the rule of the Dalai Lamas over Tibet, is a flawed system of governance for a modern State. Even in the past, it has been unsatisfactory, for several reasons.

Firstly, one is never sure that the choice of a new reincarnated lama is the right one. During some troubled periods of Tibetan history, the Mongols or the Manchu dynasty did use their influence to impose their choice.

Then, there is a gap of 20 odd years, between the death of a Lama and the time when his reincarnation is able to take over the job; during the interregnum, the Tibetan nation was often left without governance.

Should the system continue, it is certain that there will be two Dalai Lamas a few years after the death of the present hierarch: One enthroned by the Communist party in Beijing and one recognised by the Tibetans.

The temptation will be too strong for the political leadership in Beijing not to choose their candidate. It needed courage to take this decision.

What to predict for the future?

In the years to come, the gap between the 'aam aadmis' and their political leaders will probably continue to grow. Even those in the West who pay lip service to the Tibetan cause are usually doing so to embarrass China only.

The popularity of the Buddhist monk will continue to increase with little practical consequence for his countrymen in Tibet. This is one of the great tragedies of our times.

But the situation is far from being hopeless. According to Chinese statistics released a few days ago, the Communist Party of China has a membership of 88 million, at the same, it is estimated that there are 200 to 300 million Buddhists in China. This could bring tremendous change in the Middle Kingdom.

What about the Dalai Lama teaching the Buddha Dharma to China?

Only the future will tell us, but this could very well be the ultimate fate of the Lama.

© 2025

© 2025