Unlike Al Qaeda, ISIS recruiters are proactive and internet savvy.

They know there is angst among Muslims about their helplessness even in a vibrant democracy like India, leave alone other parts of the world where Muslims live.

So ISIS feeds them a regular diet of the golden age of the Ummah, creating for these youngsters a live yet make-believe world which is completely disconnected from the reality around them, says Syed Firdaus Ashraf.

When Al Qaeda's threat loomed in the early 2000s, India seemed a safe haven at peace with itself.

Post the 9/11 terror attacks and the war against terror that followed, when there was fear of the conflagration enveloping regions around it, Indians would proudly claim that not a single Muslim from the country was caught in Afghanistan fighting for Osama bin Laden or, for that matter, the Taliban.

In 2007, then national security adviser M K Narayanan stated in an interview, 'No Indian Muslim is involved in Al Qaeda,' the only exception then having been Kafeel Ahmed, the Bengaluru resident who blew himself up at Glasgow international airport.

Sure, there was a time when the Indian Mujahideen seemed to have captured the Muslim mindspace, but how this threat was thwarted is a story waiting to be told, a book waiting to be written, a film waiting to be made.

I felt happy at the way Indian Muslims had insulated themselves from terrorist influences like Al Qaeda. Not that attempts were not made to infiltrate the third largest Muslim population in the world, feed them tales of victimisation and discrimination, fuel their sense of alienation, stoke their anger into taking up arms against the Indian State.

I wondered: Why did Indian Muslims not succumb to this?

Mobashar Jawad Akbar is an editor revered by a generation of his tribe, his incisive analyses of the Hindu-Muslim riots of the 1980s a must-read for any student of post-Independence Indian history and politics.

In the days before he embraced the BJP, when he spoke at an event in Mumbai post 9/11, asked M J Akbar why Indian Muslims did not flock to Al Qaeda.

Akbar's answer: "Democracy." Then he expanded a little to say, "Indian Muslims have democracy."

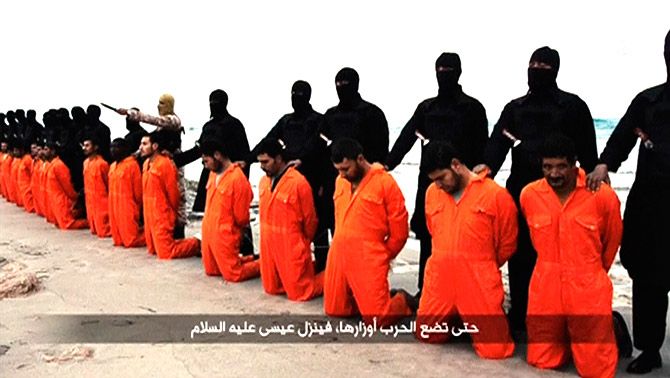

Around three dozen Indians have been linked to ISIS, and at least a dozen have joined the terror network to fight in Syria, some have been caught before they took a flight and returned to their families.

The figures are not startling for a community of 172 million, but things have certainly started to change. Given digital India's penetration, it is anybody's guess how many young Muslim minds are being whitewashed with videos and in online forums.

The threat is real and, as Dhaka revealed last weekend, not too far away.

So what has changed?

Doesn't Akbar's thesis hold true anymore?

Shia cleric Maulana Kalbe Jawad told me before the 2014 election in Lucknow, "Muslims can form a government (with their vote), but they don't have the numerical strength to make a government fall."

What Kalbe Jawad meant, and what Muslims believed, or were made to believe, was that their vote was crucial in deciding who formed the government in New Delhi. They were reconciled that the top job in the nation may never be theirs, but took consolation from the fact that they decided who sat on Dilli's singhasan.

Why, even a titan like Atal Bihari Vajpayee lost in May 2004 when the Muslim vote migrated en bloc to the Congress.

Election 2014 put paid to this belief among the community. Narendra Modi may have won a few Muslim votes here and there, but it is no secret that the community's vote did not matter for him.

Perhaps for the first time since 1952, India had a government that did not depend on Muslims voting for it.

Nothing wrong with this. Looking at it objectively, democracy is all a game of numbers with endless permutations and combinations, and Modi had just proved more adept at it in the face of the retreat by the secular forces, that's all.

Its effect on the Muslim mindset can only be imagined, or felt. All along, Muslims felt they were a critical cog in the democratic machine, but were suddenly made to feel unnecessary.

Verdict 2014 did not alter India's democratic credentials one bit, but it altered the Muslim perception of it, and their own sense of belonging, even ownership of it.

The impact on younger Muslims -- often under-educated, mostly unemployed, leave alone the educated class -- can only be guessed. In a nation that made a show of 'Sab Ka Saath, Sab Ka Vikaas,' they were nowhere in the picture, left out to dry by the secularists who leeched off their votes, as well as the system.

To worsen matters are the hotheads of the ruling dispensation who seem answerable to no one but themselves as they go on a Muslim-bashing spree. Vigilante justice is easily meted out to Muslim youth in imagined and petty cases, with no one raising their voice, not even an M J Akbar who in his prime would have shed copious tears in prose at what is happening around him.

In mercurial Akbar's place we have today's pugnacious icon Arnab Goswami who gets to interview Prime Minister Narendra Modi but ends up lobbing soft balls at him. Couldn't inquisitor Goswami have asked Modi why Muslim cattle traders were being made to eat cowdung and drink urine in his India?

So what comes to the aid of the young, disheartened, Muslim youth? Imagined communities, courtesy digital India -- aka social media.

It is on social media that the imagined community of Muslim Ummah is formed, an imagined community that brings together misguided, misinformed, youth to the era of 7th century Arabia, which they feel was the community's golden age.

The idea of a caliphate, the institution abolished by Kemal Ataturk in the early 20th century with the end of the Ottoman empire, has always been a distant dream, a suppressed longing in the Muslim community, and it was this deep desire that ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi tapped into by proclaiming himself the new caliph.

In his 1983 classic Imagined Communities on Nationalism, Benedict Anderson writes of how even the smallest nations never know most of their fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.

In the same way, ISIS members or its supporters never meet, hear or speak to each other, and yet, thanks to all-prevalent social media, they lead their lives in the image of their Ummah communion.

Unlike the Luddite Al Qaeda, ISIS recruiters are proactive and internet savvy. They know there is angst among Muslims against their helplessness even in a vibrant democracy like India, leave alone other parts of the world where Muslims are housed.

So ISIS feeds them a regular diet of the golden age of the Ummah, creating for these youngsters a live yet make-believe world which is completely disconnected from the reality around them.

Having created this mythical monster, the next step is to feed it. And this is where the 'Other' comes in, who could be anyone. The Shia, the Yazid, the Muslim woman who refuses to cover her face or recite the Quran, the Muslim youth who refuses to abandon his non-Muslim friends even in the face of death.

They are all the 'Other', the 'Kufr', the 'disbelievers' who need to be exterminated if the Ummah were to regain paradise.

The Indian Oil employee from Jaipur arrested for his ISIS links or for that matter @shammiwitness from Bengaluru may not have anything in common between them, but they bond together in this 'imagined community' of the Ummah.

In his book Pathway to Pakistan, Choudhry Khaliquzzaman writes of how he and his friends from Aligarh Muslim University decided to help the Ottoman empire, representing the Ummah, in the Balkan war of 1912-1913 by sending a medical mission to Turkey.

Islam was the cause that rallied them and they reached Turkey to save the caliphate. On reaching Turkey, they realised they did not speak the local language and there was no way they could correspond with the Muslims there.

When they met Ottoman general Anwar Bey (or Enver Pasha, who was responsible for the Armenian genocide), they failed to communicate with him as he only spoke Turkish. However, that did not stop the Indians from their mission.

The same is the case with the Indians who are in Syria to fight for ISIS in a war they have no stake in. They can neither speak nor understand Arabic, but are ready to fight for the cause of the imagined community of the Ummah, just as Khalquzzaman and his friends did in 1912.