Medical seats for under-graduates and post-graduates remaining vacant in the NEET era, together with the Centre 'freezing' the number of medical colleges and seats in (Dravidian) Tamil Nadu and the launch of the PM's 'Vishwakarma Scheme' for the nation's craftsmen, are all seen as a bid to further reverse the state's progressive socio-economic agenda of and its achievements of the past hundred-plus years, argues N Sathiya Moorthy.

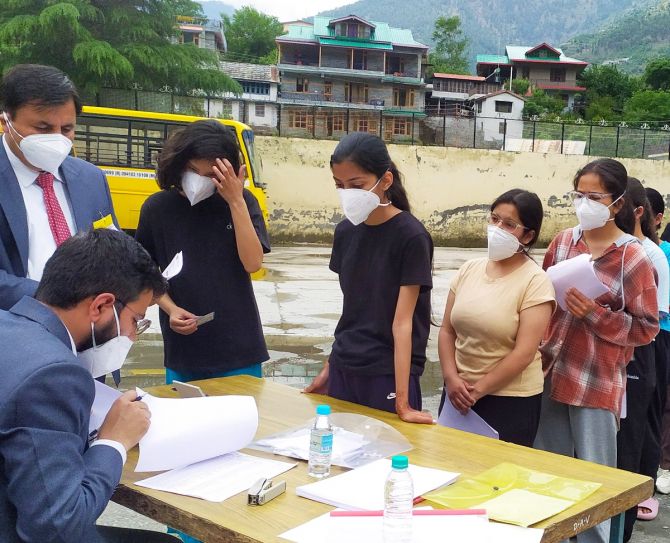

News reports quoting officials and official statements have talked about medical seats for under-graduates and post-graduates remaining vacant in the NEET era has given a stick for the critics in Tamil Nadu to attack the Centre and the ruling BJP, if not the Supreme Court, the prime initiator.

Together with the Centre 'freezing' the number of medical colleges and seats in Tamil Nadu and the launch of the PM's 'Vishwakarma Scheme' for the nation's craftsmen days earlier, it's seen as a bid to further reverse the state's progressive socio-economic agenda of and its achievements of the past hundred-plus years.

According to official information, after three rounds of counselling this academic year, close to 1,650 MBBS seats, including 483 in Tamil Nadu, and over 8,000 PG seats after first-round counselling, still remained vacant.

The PG vacancies were 3,744 the previous year. Estimates put the total number of PG vacancies at around 65,000 since the commencement of the NEET scheme, indicating a severe shortage of super-speciality doctors in the years to come, if not already.

This has forced the government agencies in charge of medical admissions to lower NEET eligibility for PG courses to zero-mark this year.

The pre-fixed cut-off marks this year was 291/800 for general category applicants and 257/800 for those in the reserved category.

Though the Centre has since clarified that this does not mean that even those that obtained a zero would automatically be qualified for a PG seat, it does imply that all those who had appeared for NEET would be eligible for participating in post-exam counselling, independent of their scores.

Just now, the medical fraternity is divided over the question if the government decision, beginning with the low cut-off marks followed by waiver of the same, will help maintain 'quality', which NEET was supposed to usher in.

Though there is a specious argument that most vacancies this year were caused by qualified applicants not getting the streams of their choice, there is the other side, which has always claimed that NEET by itself could not ensure quality -- but only elimination. As the figures for the past years show, it is not a one-off affair for the year, as claimed.

The 'elimination', more so at the under-graduate level, especially according to multiple Dravidian parties, is of students belonging to socio-economically weaker sections of the society, residing mostly in rural boondocks and going to non-fashionable government schools.

Both the ruling DMK and the predecessor AIADMK administration and multiple political parties barring the BJP have all along been seeking a reversal to the earlier scheme of state-level admissions based on Plus-Two board exam marks.

Tamil Nadu fixed Plus-Two marks as the qualifier in 2007 after scrapping the common entrance test for medical admissions that the state government had introduced years earlier.

The latter was aimed at eliminating malpractices involving private entrepreneurs in medical educations, with management quotas, capitation fees and high fees -- and the former was introduced later, acknowledging the absence of high-cost, high-quality tuition access to students from poor and rural families -- thus filling the artificially-recreated elite-non-elite, rich-poor divide, which the Dravidian scheme had sought to eliminate all along.

The irony, as is being pointed out, is that the Medical Council of India, now rechristened as National Medical Commission, like the Tamil Nadu government earlier, had thought of a common entrance examination across the country in 2009, only to take the pressure off the students, as they had to prepare for multiple entrance exams under different formats, with some examinations overlapping on the same day.

Travelling to those multiple exam centres was tedious, time-consuming and costly.

Yet, when it rolled out of a five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in 2016, no one was talking any more about the comfort and convenience of the students, but only about the quality of medical education -- and the high standards that were expected of medical professionals in the 21st century India.

Incidentally, a three-judge Bench of the court had ruled against a common entrance test, 2-1, three years earlier. And Justice Anil R Dave, who was the dissenting judge in 2013, got to head the Bench in 2016 -- he did not recuse himself as used to be the tradition -- but the ruling was unanimous.

It's against this background that the incumbent government of DMK Chief Minister M K Stalin appointed the Justice A K Rajan Committee in 2021, which in turn reported that most students who had cleared NEET in the past years had undergone private tuitions for months, costing lakhs of rupees -- and available only in urban centres.

Even though access has now become easier with online classes, still the cost remains prohibitive and internet facilities not always reliable in rural and peripheral areas.

There is then the argument that minus a qualifying examination for a profession like medicine, the nation and governments were risking the lives of innocent multitudes, rich or poor, at the hands of under-qualified doctors, whether under-graduates or PG-holders.

NEET-critics in Tamil Nadu especially -- even BJP-ruled Gujarat was opposed to a common entrance exam when first mooted -- claim that the argument did not hold, and for multiple reasons.

One, an aspirant becomes a doctor only after completing a four-year course, followed by exams and a year-long internship, which is gruelling and thorough at the same time.

S/he does not become one at the entry-point, for anyone to determine his future calibre, based on the marks s/he scores in her/his Plus-Two exams or NEET.

Hence, the only outcome of the 'NEET ideology' -- yes, they go as far as to call it an ideology -- was to keep the rural poor out of the mainstream, which states like Tamil Nadu with their long history of 'affirmative action' have achieved and do not want to lose out on. This, they say, goes beyond politics and elections.

It is in this context, they recall how while joining the nation's facilitation of ISRO's successful Chandrayan-3 team, DMK members in the Lok Sabha reeled out the names of top space scientists of our times and pointed out how they all came from poor and rural backgrounds, went to government schools and to less-than-impressive engineering colleges.

The implied message was this: Given the opportunity and exposure, such students from such backgrounds, both socio-economic and academic, can prove themselves equally well in medicine or any other profession requiring exactitude of the space programme kind.

These critics readily agree that owing the lack of exposure, many of these students, especially in the initial years -- starting with the counselling sessions -- are poor communicators.

They needed coaching, training and exposure, the last of which they get during the course of their medicos' life, which, they say, also make up for the absence of other two, up to a point.

Stalin has since claimed that the Centre's decision on PG-Zero only vindicated the state's position -- and not just vis-a-vis the PG courses but under-graduate streams, too.

Already, the bill seeking NEET exemption for the state, passed unanimously in the assembly, is awaiting the Centre's decision, after Governor R N Ravi took his time forwarding the same -- and his supporting the Centre's scheme in public, more than once.

As may be noted, nearly half of the 483 vacant MBBS seats in Tamil Nadu fall under the All-India Quota (AIQ).

In State-run colleges, where the annual tuition fee is less than Rs 20,000, there are 56 vacancies.

Worse still, a dozen seats have not been filled in AIIMS-Madurai, where however infrastructure is still coming up.

With so many vacancies, private promoters have been urging the Centre, here and elsewhere in the country, to revert the unfilled seats, to fill them under the 'management quota', or lower the cut-off marks, or both -- latter, if only in the future.

This, according to local critics of NEET, should give a lie to the supporters' argument that successive governmental opposition to the national scheme flows from the fact that many politicians in the State owned medical, dental and engineering colleges, and they all stood to lose from a NEET-based medical admission -- and how after NEET bright students from economically backward families and communities had made it to government colleges with lower fees and no 'capitation fee' of any kind.

In this context, NEET critics point out how in the state for decades now, socio-economically backward students invariably were allotted government colleges or government quota seats in private colleges -- some of them later becoming deemed-to-be universities -- not only for medical admissions, but also for engineering and other professional courses, including law.

Of course, they do not tell you that more often than not, students from economically weaker sections from the forward class communities (general category) are not allotted to government colleges, but mostly to private colleges.

It is not clear if the Centre's EWS quotas have corrected this unofficially-enforced aberration.

Better or worse still, they also recall how under NEET 15 per cent are 'management quota' seats, where the promoters can not only charge high tuition fees (and capitation fees???) but also pick and choose candidates from 'affordable background', even if they ranked lower in NEET, denying those seats to relatively better-performing students.

NEET-supporters do not highlight this aspect, the critics point out, asking how then can medical admissions based on Plus-Two marks alone be faulted.

It now remains to be seen if and how the state polity and government take up the issue afresh, in the light of the current disclosures on vacancies in UG and PG medical education.

Will they now pass a resolution again in the state assembly, highlighting the facts as brought out by the Centre and its agencies -- and also the unending stream of 'NEET suicides', including at least one this year?

Or, will they approach the Supreme Court for a review based on contemporary statistics, supported by the Justice Rajan Committee Report, to be updated if need be?

According to a less-publicised news report, a three-judge Bench of the Supreme Court headed by Chief Justice Dr Dhananjay Yeshwant Chandrachud refused to hear a counsel who challenged the zero-cut-off for PG-NEET, saying that he did not have locus standi in the matter.

It is another matter that the government had possibly diluted the 'standards' for medical professionals outside of NEET even otherwise, when it allowed qualified practitioners of Ayurveda and other forms of Indian medicine to perform surgeries -- a very complicated procedure near-exclusively in the allopathic domain.

It is against this background that the news of central agencies fixing a 1:10-lakh population requirement for every 100 MBBS seats, with a 150-seat upper-limit for a college, threatens Tamil Nadu's policy of having one medical college with hospital in every revenue district.

As may be recalled, when the predecessor AIADMK government of chief minister Edappadi K Palaniswami created six new districts, 2016-21, the state government almost alongside announced as many new medical colleges.

Incidentally, the BJP at the Centre, then an electoral ally of the AIADMK, cleared the proposal without fuss and much loss of time.

Though the current decision may have nothing whatsoever to do with the political adversity, at times bordering on animosity, between the ruling parties at the Centre and the state, it definitely can upset the doctor-population calculus, if over the years.

Now comes the third issue, of Prime Minister's Vishwakarma Scheme for funding and aiding artisans and crafts-persons cross the country.

In Tamil Nadu, critics see it as an extension of the Centre's 2015 proposal to 'relax child-labour laws' to allow those below 14 years to 'work in select family businesses'.

The idea did not get propagated, and hence was not known to most people at the time.

According to Tamil Nadu critics, the Vishwakarma Scheme was only a rehash of the chief minister C Rajagopalachari's 'despicable Kula Kalvi Thittam', or 'clan-based' or 'tradition-based' skills education.

The likes of Dravidian ideologue E V Ramaswamy Naicker 'Periyar' and DMK founder Annadurai called it thus.

They argued that the aim was to ensure that a carpenter's children remained a carpenter and a potter's son, potter, while a Brahmin bureaucrat's son (alone) qualified to become a bureaucrat in his time.

The Rajaji administration's (1952-1954) idea was only to make judicious use of available school buildings and infrastructure, to draw in more students to the elementary schools, whose numbers were low and to build new ones, the government did not have funds.

It meant that children from first to fifth standards would attend classes either during the forenoon or afternoon session.

Assuming that was giving a wise alternative for those children to spend their time usefully at home, Rajaji went out of the prepared scheme, to say that they could learn their family's traditional skills and crafts during the other half.

When criticism mounted, in a fit of anger, Rajaji told a public meeting that, yes, it was 'Kula Kalvi Thittam', as they had christened it.

The critics, starting with the then state Congress president and successor chief minister K Kamaraj, had already gone all out, criticising Rajaji as being 'communal', leading to his resignation.

Going beyond the Vishwakarma Scheme, on the medical education front itself, the state now has a doctor-to-population ratio closer to those prevailing in Scandinavian countries.

Any reversal, especially attributable to the Centre and its agencies, while having social consequences can trigger the kind of 'Tamil angst', which alone caused the 'Jallikattu protests' in 2017 -- and which in a future generation and under a leadership that the present one has no clue about, could have ideas and equipment going beyond peaceful mass protests of the Jallikattu-centred ones, and just for a week at the time.

N Sathiya Moorthy, veteran journalist and author, is a Chennai-based policy analyst and political commentator

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025