'I doubt very much if I will ever move on from his music, as I have from so much else through the years,' says Aakar Patel.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

In 1980 or so, when I was around 10, my father bought my sisters and I a present. It was a cassette player, one of those mono boxes that are no longer to be found, and a few cassettes.

These were the soundtrack to a Hindi movie, Rishi Kapoor's Zamaane Ko Dikhana Hai, an album by the Caribbean band Boney M called Nightflight to Venus, an anthology of the Swedish band Abba and, less predictably, Man Machine, an album by the German electronic group Kraftwerk.

I remember them well because in the months that followed we played all four so often that they wore out.

My father was a man of eclectic tastes and had probably consulted the store he was buying the tapes from (most likely Rhythm House at Kala Ghoda) what the current good music was.

He himself listened to music on a record player and he had a collection of some 500 LPs, all of which were lost during the Surat floods of 2006.

He had a fondness for old Hindi music, but, by the time I am writing about, had begun to prefer more sombre music.

This came in the form of the ghazal, which was being popularised by such singers as the Pakistani Mehdi Hasan (my father's favourite) and the silver-voiced Punjabi singer Jagjit Singh.

We were exposed to this music early and that made us unusual.

It may interest readers to know that till about 50 years ago, the ghazal was not particularly sung in the popular form.

A few literate and high-culture communities in the North were familiar with the works of Ghalib, Zafar or Mir, but the singing of these works, along with those of of more modern poets like Faiz, is quite recent.

We lived in Surat and there was otherwise little access to the outside world, but fortunately I was friends with some boys five years or more older than I was and they had good music.

This is how I was introduced by the early teens to the music of Simon and Garfunkel and The Beatles and then, as I was slightly older, bands like The Who and Pink Floyd.

One of my friends was quite interested in playing music of this sort and he was from a wealthy family with access to all sorts of instruments. He was playing music through a computer on a sequencer 25 years ago.

With him I learned how to play a little bit of guitar and we spent many afternoons over a few years till I left Surat.

Through all this time, there was also other music that I was exposed to, mainly through years of playing tabla, something that my parents insisted I do.

This was a terrific gift to a child, and though I thought of it then as a chore, and can no longer play with any degree of competence, I still have the elementary knowledge of taal (beats) retained and can thus enjoy music much more today.

I continued to listen to the popular music of the West for a few years more, through my years in college and till I was in my mid-20s.

This was also the period in which I migrated to Bombay, as it was then called, and because I was now working and living in modest spaces, there was not that much scope to listen to music.

When I was 27 or so, my to-be-wife introduced me to the music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and this was an epiphany, a moment of revelation and clarity.

I knew instantly that I would like and listen to this form of music, meaning that linked to mysticism, for a long time.

In the years that followed I remained very devoted to the form. I heard qawwali at many dargahs and I was able to understand the spirit behind it in such places as Nampally in Hyderabad and Baba Shah Jamal in Lahore.

When I was able to afford better equipment I bought it and built a collection of music (now on CDs). Unfortunately, more time was spent acquiring this collection than listening to it.

Music is something that we turn to, in the same way as food, for comfort, and therefore we do not experiment too much.

My father's eclecticism, I understood now, was unusual and rare.

In my 30s, I had another moment of departure in music.

This time it came through my reading, which told me that to really understand Western civilisation, it was not enough to know its primary texts or to be touched by its popular music.

One had to engage with its classical roots, and to know what role such things as harmony and counterpoint in music were reflected in Western culture and society. Because this realisation came through reading and not viscerally, this music was more difficult to engage with.

I began attending the concerts of the Symphony Orchestra of India, which was then just being formed. I read up on what would be played on that particular day and would listen to the pieces before so I could anticipate the music and not be bored.

It was pleasant as an experience, though that music lacks the intensity and the emotion of our music, but it was fantastic as a method of learning. I have since left Mumbai and have no access to live symphonic music.

These days I listen to very little music. If I am alone I read.

When there are guests at home, I play non-vocal music, some jazz perhaps, in the background through an app.

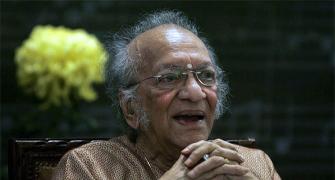

On YouTube, I have about 100 tracks that I have set as my favourites. Most of this is Hindustani music, the majority being songs by Kumar Gandharva.

I discovered his music in my 40s. He was a genius. His contribution was three things in the main.

First, he dismantled the gharana tradition comprehensively.

Pupils were no longer required to mime their teachers because of his innovation, as they had been doing since the beginning of the gharana system.

Second, he paid great respect to lyric and sang the raag through the composition. He didn't just mumble words as was -- and is -- the tradition of Hindustani's masters.

Third, he used the local poetry of Central and Northern India and set it to music.

He is a companion for all time. I doubt very much if I will ever move on from his music, as I have from so much else through the years.

V S Naipaul, an Indian by ethnicity but not by culture, was able to penetrate our feeling for our music quite effectively in the novel A Bend in the River. He describes precisely how we Indians feel at a point in musical time, when we say: 'Wah!'

It is a warm and lovely feeling, and I have been privileged to have felt it many times in my life.