The India-US nuclear deal was aimed at ending India's nuclear isolation and nuclear apartheid, recalls Rup Narayan Das.

A milestone in the relationship between India and the USA which the late prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh wove against odds was the civilian nuclear treaty announced by then American president George W Bush on July 18, 2005 during the former's visit to the USA.

In 2008 the deal, called the 123 Agreement, was formally signed by both sides. The deal was considered an important step from India's point of view.

The deal aimed at removing the embargo on India having any access to civil nuclear technology or nuclear fuel from outside India.

The embargo was imposed on India after India's 'Peaceful Nuclear Explosion' at Pokhran in May 1974 and after the creation of the Nuclear Suppliers Group.

The nuclear deal was aimed at ending India's nuclear isolation and nuclear apartheid. India was denied high technology in the field of nuclear energy.

The nuclear aeal envisaged to enable India to import nuclear reactors from France, Russia, Canada and other countries.

The deal enabled India to have access to nuclear fuel from these countries.

It had two broad objectives -- meeting India's strategic objectives and providing energy security. Ever since there has been no looking back.

In both India and the USA, there is bipartisan support for the strategic partnership between the two countries.

The stand-off of the ruling United Progressive Alliance government led by Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh with the Opposition parties, particularly the Left parties, over the nuclear deal was primarily on ideological grounds.

The Left bloc felt that India was bowing before the USA. They were concerned that the USA would bully India into submission by threats and warnings.

The Left had 61 members in the Lok Sabha and could swing the balance of power for the UPA coalition.

The BJP was expedient, given that it was the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government that had initiated a dialogue with the US to get this very result.

In Parliament, Dr Singh tried to allay the anxiety of the Opposition, particularly the Left parties, that there was a 'secret deal' behind the public one, and denied that India was entering into a military alliance with the US against China.

He also assured Parliament that the negotiation with the US would not hurt India's strategic nuclear programme.

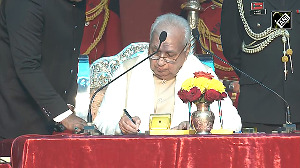

Dr Singh's government won the trust vote 275 to 256. Photograph: Reuters

Separation Plan

A great challenge for the nuclear deal was the 'separation plan' which the two sides negotiated between August 2005 and February 2006.

India had 22 nuclear plants in 2005. The US suggested that India classify some of these as required for its strategic nuclear weapons programme.

Within these 22 atomic plants, including two research reactors, India wanted 14 separated as civilian facilities that would be brought under International Atomic Energy safeguards.

Outlining some salient features of the Separation Plan, Prime Minister Singh, in a statement in the Lok Sabha on March 7, 2007, said, 'the Separation Plan will not adversely affect our strategic programme.'

'There will be no capping of our strategic programme, and the separation plan ensures adequacy of fissile material and other inputs to meet the current and future requirements of our strategic programme, based on our assessment of the threat scenarios.

'No constraint has been placed on our right to construct new facilities for strategic purposes.

'The integrity of our nuclear doctrine and our ability to sustain a minimum credible nuclear deterrent is adequately protected.

'Our nuclear policy will continue to be guided by the principles of restraint and responsibility.

'The Separation Plan does not come in the way of the integrity of our three stage nuclear programme, including the future use of our thorium reserves.'

The then Lok Sabha Speaker Somnath Chatterjee on August 17, 2007 rejected the Opposition's demand for re-negotiating the nuclear deal, saying that Parliament had 'no competence' to decide on the operationalisation of any international agreement or treaty.

Speaker Chatterjee quoted the Constitution and said in the absence of appropriate laws drawn up by Parliament, the central government's right to enter into treaties and agreements with foreign countries in its sovereign power is unrestricted and becomes effective without any intervention by Parliament.

'It is also well established that there is no requirement to obtain ratification from Parliament of any treaty or agreement for its operation or enforcement,' the Speaker ruled.

Thus, Parliament can only discuss any treaty or agreement entered into by the government without affecting its finality or enforceability.

Speaker Chatterjee decided that the issue would be discussed under Rule 193 that has no provision for voting.

The nuclear deal polarised Indian politics to such an extent that it forced the UPA coalition government to seek a vote of confidence in the Lok Sabha on July 21, 2008 following the withdrawal of support by the Left parties on the issue of the government's initiative of seeking international cooperation in the development of civil nuclear energy.

A special session of the Lok Sabha was convened for the purpose. The House debated the motion for more than 12 hours over two consecutive days suspending even Question Hour.

It was indeed unprecedented. The government was in a hurry to seek the confidence of the House as a general election was due in a few months entailing uncertainties about the fate of the nuclear deal.

Civil Liability for Nuclear Liability Damage (CLND) Act 2010

Yet another achievement of the late prime minister related to the nuclear deal was steering the Civil Liability for Nuclear Liability Damage (CLND) Act 2010, a legislation that was enacted by Parliament to ensure a speedy compensation mechanism for victims in case of a nuclear accident.

This can be singled out as the biggest reason for the stalemate on the engagement between India and the USA on nuclear transactions.

Some provisions of the Act were perceived as a hindrance for the supply of equipment by US reactor vendors and sub-suppliers.

The significance of the Civil Nuclear Liability Act can be hardly overemphasised in the backdrop of India's disastrous experience with the Union Carbide gas leak tragedy in Bhopal.

The Act envisaged prompt payment of compensation to victims in the case of an unforeseen nuclear accident.

While Parliament itself evinced unprecedented concern in the nuclear deal, the treaty itself entailed legislative enactments like the Civil Nuclear Liability Bill which was subjected to scrutiny by relevant parliamentary ommittees.

The remit of the Act is very broad and comprehensive.

It defines 'nuclear damage' meaning loss of life or personal injury to a person, or loss of, or damage to, property caused by or arising out of a nuclear incident resulting in any economic loss.

The loss of damage may arise out of, or result from ionizing radiation emitted by any source of gradation inside a nuclear installation, or emitted from nuclear fuel or radioactive products or waste in, or of nuclear material coming from, originating in, or sent to, a nuclear installation.

Rup Narayan Das is a former senior fellow at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses and at the Indian Council of Social Science Research. The views expressed are personal.

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com

© 2025 Rediff.com -

© 2025 Rediff.com -