'If India is to emerge as a superpower, we must utilise our huge agricultural potential and not, as in past centuries, merely exploit our farmers,' says Colonel Anil A Athale (retd).

As a former infantry soldier, one feels a natural affinity to the farmer. While on a patrol, in blinding rain, one has often seen farmers working in their fields.

Farmers and soldiers are among the few professions that have a close relationship to the earth -- the soil of the nation.

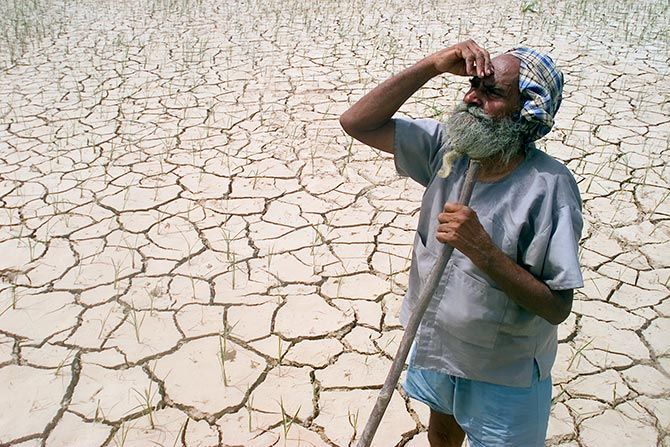

The recent events when farmers went on strike in many states and turned violent over the crash in farm produce prices evoked a natural sympathy.

The farmer, not unlike a soldier (who is damned if he uses force and is killed if he doesn't), faces a double whammy.

Dependent on Nature, he finds consumers up in arms over the rise in prices when his crop fails.

The result? The government clamps down on prices, stops exports, resorts to imports and makes sure the vocal urban consumer is kept happy.

The case of periodic 'onion crisis' is too well known to bear repetition.

But the same vociferous media is mostly silent when there is a glut and prices crash.

I have been travelling to various developing countries in South East Asia for the last 10 years or so and can say, without any fear of contradiction, that India has the lowest prices for fresh farm produce in all of Asia.

There is no comparison, of course, to prices of fresh food in developed countries, where these are twice or three times more than India.

Our inefficient marketing system, where cartels of traders fix prices, completes the circle of misery for the anna daata (food giver) of our country.

But the good news first!

Older people like me remember the 1950s and 1960s when the Soviet Union was the flavour of the season.

Our first prime minister was smitten by the Soviet programme of 'collectivisation' of farms.

He also felt 'State farms' were the answer to India's problem of lack of food supply.

An experimental State farm was established in Suratgarh in Rajasthan. But -- thank God for concerted opposition from the farmers' lobby and the right wing of the Congress party! -- this mad project remained in the experimental stage.

Imagine the situation if Nehru had succeeded in 'nationalising' farming. We would have seen food riots and hunger in the country like the erstwhile Soviet Union experienced in 1991-1992 (when India gifted it two million tons of wheat).

China under Mao flirted with the collectivisation of land and the commune system in villages. Luckily for that country, better sense prevailed and farmers got back their small plots.

Under our notions of a 'socialistic pattern of society', all governments -- irrespective of party labels -- put shackles on the farm sector.

In India, despite the liberalisation of 1991, agriculture remains the most controlled sector of our economy.

The farmer is subjected to all types of control in terms of pricing, movement of produce and to whom and how he sells it.

Remember the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee Act?

To these restrictive laws, a recent addition is the prohibition of selling his livestock under the influence of 'cow zealots'.

Then we have Western-educated (?) economists periodically floating the idea of an 'agricultural income tax.'

They also want investment in shares for one year to be tax free, but want to tax farmers who invest for similar period, labour hard, face uncertainties due to weather and yet produce the most important 'public good' -- food!

These phoren economists and advisors also conveniently forget to tell us the kind of massive subsidies that all developed countries give their farmers.

The urban bias of our policy makers is not a new thing.

Indeed, the roots of Indian agrarian crisis go back almost one thousand years.

In Indian history, till the first millennium, farming was regarded as a noble profession.

The farmer often doubled up as a soldier in times of war.

The kings took active part in sowing operations, often ceremoniously ploughing the land with a golden plough to begin the farming season.

Around 1100 AD, there emerged a class of rulers who were fulltime soldiers and kept themselves busy with constant wars.

This was particularly true of north and central India where, thanks to abundant water, farming was a round-the-year vocation.

The Muslim rulers who replaced the warrior clans were city-based rulers, with no roots in the soil and villages of India.

They had neither any empathy nor consideration for the rural folk who entered the picture only when it was time to collect revenue.

With the notable exception of Sher Shah Suri, it will be fair to say that very few, if any, public works were carried out to benefit farmers.

This is in sharp contrast to, say, Europe, where most irrigation works and infrastructure was created nearly 200 to 300 years ago.

The impressive monuments of the Mughal era in the north, or in places like Bijapur in the south (the Gol Gumbaz), show that Indians had the requisite engineering skills needed to dig canals or build dams.

What was lacking was the will of city based rulers who, for a long time, never thought themselves to be Indians.

Sadly, India's post- Independence rulers have continued with this legacy.

The British were here to exploit the resources of India for their country.

Their rule saw disruption in normal crop patterns.

They introduced new crops like jute, indigo and tea for their benefit.

Even 70 years after Independence, we have not seriously questioned the distortions introduced by the British.

If India is to emerge as a superpower, we must exploit our huge agricultural potential.

Food is a strategic commodity and, if needed, farmers must get regular 'grants' to continue their activities, not just loans.

The terms of trade, presently tilted heavily in favour of the urban consumer, must be changed to balance the interests of farmers as well.

But, first and foremost, our urban elite must give up their skewed world view borrowed from the West!

Colonel (Dr) Anil A Athale (retd) is a military historian.

© 2025

© 2025