The Jallikattu issue has revived pan-Tamil political sentiments especially among youths, says N Sathiya Moorthy.

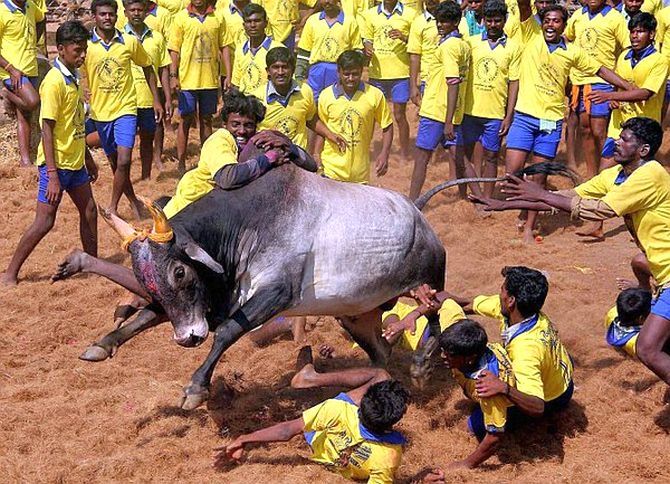

This year's Pongal season has seen the Supreme Court ban on the annual Jallikattu taking a 'pan-Tamil nationalist hue' after protests erupted across the state's southern villages for restoring Tamil Nadu's culture and tradition.

With some state-level leaders of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party cautioning the protesters and the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam government about any precipitate action leading to Central intervention of the 'dismissal kind' under Article 356 (obviously under the directions of the Supreme Court, if it came to that), the political and social media outcry only needled the southern state even more.

It is for the first time since the SC ban in 2014 that Jallikattu has assumed such a GenNext context, breaking all caste and sub-regional barriers.

Confined to the central and southern district of Tamil Nadu where the warrior Mukkulathor community dominates politics and society, this time, improvised, last-minute Jallikattu of sorts came to be staged in other regions too.

Non-Mukkulathors and non-Hindus also posed before TV news cameras, giving it a unified pan-Tamil cultural hue. But peripheral groups did not lose the opportunity to try and revive the 'Tamil nationalist' sentiments which has revived after decades of 'Dravidian rule'.

In the run-up to 2016 elections, the pan-Tamil political sentiments had begun losing the fervour and flavour that it had once assumed decades earlier before the commencement of ‘Dravidian rule’ in 1967 -- and revived with the end of the 'ethnic war' in neighbouring Sri Lanka.

Until now, the long hospitalisation of former AIADMK chief Jayalalithaa, her subsequent death and internal affairs of the party afterwards, along with demonetisation crisis at the national-level, all had taken the front seat in the state’s news coverage and political discourse.

Possibly with the AIADMK crisis settling down for now, the simmering Jallikattu row may have provided the platform for a tectonic shift in Tamil Nadu’s political discourse, even if for the interim.

The process may have been facilitated or reactivated by the presence of two Mukkulathor leaders at the helm of the ruling party affairs in the state. Chief Minister O Panneerselvam and AIADMK’s new general secretary, V K Sasikala, both belong to the community, though to different sub-sects.

Not that either of them spoke in favour or against conducting jallikattu, defying the SC ban, but their very presence at the helm carried message(s) and consequence(s) of their own.

After holding out protesters for a day on ‘Mattu Pongal Day’, the second of the three-day harvest festival dedicated to cattle on Monday, the police began to act against them.

It was not unlikely that the police had not only to do, but also seen as doing it if only to not create the impression (especially in the eyes of the Supreme Court) that the state government was siding with the protesters or was being sympathetic to their cause, most of whom visibly belonged to GenNext on TV screens.

Social media activism has since taken on a new hue. From defending Tamil culture and traditions, which in this case date back possibly to multiple millennia, to a pan-Tamil idea that they claimed the 'Indian system and schemes were challenging, testing or (wantonly) alienating'.

Suffice to point out that not just in Tamil Nadu (including non-traditional sub-regions of the state) but also ‘wherever world Tamils lived’ (an euphemism that includes Sri Lankan Tamils, especially), protests against the SC ban in India were staged.

This is not to belittle the local efforts or its effect. As the Tamil media began pointing out, the Jallikattu ban seemed applicable only to the state, but not to neighbouring Andhra Pradesh where one was conducted in the native village of Chief Minister N Chandrababu Naidu with the customary fun and fanfare.

That Jallikattu is more about tradition and least about cruelty to animals should be amplified if one considered that elsewhere in the state, people on the same day would catch a forest fox and let it loose after a ‘darshan’.

In neighbouring Karnataka, in some places, cattle are made to jump through a bonfire, to protect them and their owners from evil eyes in the new harvest season and afterward too.

That way, there was greater danger of bystanders, more than Jallikattu animals or their catchers getting hurt/killed until the state government began enforcing a Supreme Court direction for the respective district administrations to ensure all-round safety, only a few years ago.

In the immediate context, suffice it to point out that BJP national secretary H Raja, a chartered accountant by training and profession, had his bullock participate in a ‘manju-virattu’ game in his native place, seeking to differentiate it from Jallikattu proper -- and unconvincingly so.

Raja’s colleague and minister of state at the Centre, Pon Radhakrishnan, walked further to defend the impromptu Jallikattu organised in villages, saying that it was only a non-violent protest by the local youth and did not amount to any violation of the SC ban -- or, words to that effect.

Other political parties, like the Opposition Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and the Vanniar-centric Pattali Makkal Katchi, the latter still licking its electoral wounds from the May elections, were hesitant in entering the scene.

But the social media-initiated protests, with no leadership or direction, to call their own, left them all with little or no choice. The DMK in particular started joining issue after AIADMK’s Sasikala challenged opposition stalwart M K Stalin whose party had contributed more to the ban, or did little while in the power to have it lifted.

Having waited it out, unlike on other pan-Tamil issues like Cauvery water dispute and the Sri Lankan ethnic war, lawyers across the state too have joined the protests. They have also promised to take up the cases of those arrested for defying the ban in traditional Jallikattu centres like Alanganallur and Palamade, or in other places across the state, including metropolitan Chennai, the state capital.

It was in this melee and milieu that peripheral pan-Tamil parties, consistently losing their electoral identity over the past couple of years even more than earlier, found new issues.

It was thus that the Naam Thamizhar Katchi (‘We, the Tamils’ party), among others, joined issue especially on threats of Central intervention, or SC direction to the effect.

Party leader and one-time film-maker, Seeman, argued that dismissal of the state government in context would become acceptable only after a decision was taken against neighbouring Karnataka for defying successive Supreme Court orders on the Cauvery waters row, and against Kerala on the Mullaperiyar court orders.

For the Centre, the likes of him had another argument, emanating from the Cauvery water issue, and pointed out how the Modi government had changed tack days after accepting the SC direction to appoint the Cauvery Management Board last year.

Revisiting the past practice, when their multi-million films shut down at Sri Lankan Tamil centres, across the world in particular, and over the Cauvery water dispute nearer home, Tamil film artistes have lost no time in backing the ‘culture-based’ defence of reviving Jallikattu. However, their views on the pan-Tamil aspects of the cause are not known.

It was not without immediate reason or provocation. Youthful protesters blocked the outdoor shoot of Garjanai, a Tamil film starring actress Trisha Krishnan, after she was seen as being an activist of PETA (People for Ethical Treatment of Animals), the international NGO.

Protesters also targeted other Tamil film actors like Arya and Vishal for the same reason, but they were not shooting in rural Tamil Nadu at the time.

The fact remains that the Animal Welfare Board under the Centre was the petitioner in the Supreme Court, and the Centre thus became the real target of the protesters. PETA joined in, and social media campaign is now for the government to shut it down and sisterly organisations of its kind.

A last-minute attempt to stage Jallikattu this year (at least) was lost when an SC bench hearing the case declared last Friday that the judges were in the process of dictating the verdict, and they could not be rushed.

This also meant that pending the eagerly-awaited SC verdict, neither the Centre, nor the state government could consider promulgating an ordinance that could have constitutional consequences not thought of by the Founding Fathers.

For now, the youthful protesters have vowed not to let their cause wither away as in the past years after the ban, or on other issues like the Cauvery water and Mullaperiyar dam dispute -- not to leave out the Sri Lankan Tamil cause and the fishers’ row, also involving the neighbouring nation.

At the same time, the Jallikattu row did take the media focus away from the internal politics of the post-Jaya AIADMK and also the (accompanying) tax raids on those seen as being close to the rulers of the day, including then chief secretary P Rama Mohan Rao.

Sasikala’s equally ambitious and even more controversial husband, M Natarajan, however did not let Jallikattu come in the way of his annual pan-Tamil conference, organised in the temple-town of native Thanjavur.

Known as the capital city of the erstwhile Chola kingdom -- whose ‘Tiger’ standard the LTTE had adapted, incidentally -- Thanjavur suburbs also house the ‘Mullivaikkal memorial’ in memory of the fallen LTTE men, with Natarajan among the organisers, along with Pazha Nedumaran, founder of the Ulaga Tamizhar Peravai (World Tamil Conference).

Skirting the Jallikattu issue, however, Natarajan more openly targeted the BJP government at the Centre, in his valedictory speech at this year’s conference on Monday, January 16.

Natarajan, as also Sasikala’s brother Divakaran, who spoke on the inaugural day, publicly defended her taking over the AIADMK leadership, and also the ‘family rule’ in the party (alluding to them all). This definitely has upset AIADMK cadres who are unconvinced about a party role for Sasikala even now.

Natarajan in particular took the names of BJP and RSS leaders, cautioned against any political misadventure in ‘Dravidian Tamil Nadu’, where the Congress rival had not been able to revive itself even 50 long years after losing power. He also threatened to ‘expose’ those behind the BJP ‘programme’ in this regard.

Whether or not Natarajan meant what he said, one way or the other, there is no denying his strategic/tactical contributions to scuttle present-day BJP political veteran Subramanian Swamy’s efforts to topple the maiden Jayalalithaa government in the early nineties.

This time round, Swamy does not seem to be in the picture. But then, Deepa Jayakumar, Jaya’s niece, declared on MGR’s birth anniversary on Tuesday that she would unravel her ‘anti-Sasikala’ political plans on February 24, the birth anniversary of her dear aunt.

She is only attracting crowds of onlookers outside her Chennai home just now. However, she neither has a party, nor an organisation, nor MGR-Jaya’s ‘Two Leaves’ symbol (nor possibly the kind of funding required for it all).

Deepa’s possible rise, and/or the SC verdict in the pending wealth case against Jaya (posthumously), Sasikala or others, could well end up in Jallikattu getting forgotten, at least around this time next year.

N Sathiya Moorthy, veteran journalist and political analyst, is Director, Observer Research Foundation, Chennai Chapter

© 2025

© 2025