'The jurisprudence of a modern secular State has to be strictly rational.'

'Rather than aastha and aqeedah, our jurisprudence as well as the executive and legislature have to act in accordance with Constitutional rationality,' argues Mohammad Sajjad.

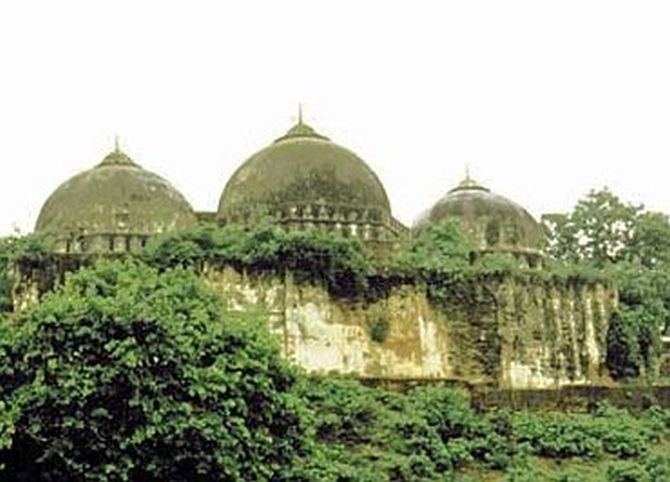

The Supreme Court, in its forthcoming hearings on the issue of the Babri Masjid, has to decide about the title suit, that is, the proprietary right to the disputed land.

It is, therefore, quite irrelevant if a mosque is really essential in Islam.

In my considered view, any misgiving among any section that the recent judgment against the essentiality of a mosque in Islam may really impact upon the judicial pronouncements, therefore, is absolutely unfounded.

Besides the proprietary rights, some more points need to be clarified.

The most important and challenging aspect of the issue is to penalise those culprits who pulled down the mosque, a heritage monument, on December 6, 1992, instigated by certain political leaders.

The Supreme Court has already stated earlier that the act of demolition of the mosque was an act of 'national shame' and that it did not only demolish an ancient structure, but the faith of the minorities in the sense of justice and fair play of the majority.

The Supreme Court has to decide this issue of vandalism as well.

The judiciary of a secular State has to be guided by Constitutional rationality and modern principles of jurisprudence rather than by aastha/aqeedah (or faith) which must remain strictly a private matter of individuals or groups.

The 'existing archaeological and literary evidence indicate that the present day Ayodhya was known as Saket before the fifth century AD. The Ayodhya of Valmiki's Ramayana, even if it did exist, was possibly not the same as the Ayodhya that was historically identifiable later,' said historian K N Panikkar.

When the historicity of a town is so difficult to ascertain, how can a specific point in the town be ascertained as the birthplace of Lord Ram?

These aspects have been examined in great details in long, well-researched essays collected in the book, Anatomy of a Confrontation: The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhumi Issue (1990), which was edited by historian Dr Sarvepalli Gopal.

Moreover, legal experts and commentators have expressed their opinion on possible flaws in the recent judgment denying the essentiality of a mosque in Islam:

1. This does not 'give any evidence from Islamic scriptures' to justify its declaration that mosques are not essential to Islam. It thus ignores the 'essential practices doctrine' laid down in a Supreme Court judgment of 1954 according to which 'what constitutes the essential part of a religion is primarily to be ascertained with reference to the doctrines of that religion itself'.

Subsequently, in 1972, the Supreme Court further elaborated upon it by asking to accommodate 'practices which are regarded by the community as a part of its religion'.

2. So far as careful readings of the Quran and authenticated Hadees are concerned, even during the days of Prophet Mohammed, 'mosques went beyond the "ritualism of worship". They were spiritual, humanitarian and educational centres open to all people irrespective of their social, financial or racial status, or gender, thus emphasising the importance of equality for social progress,' says A Faizur Rahman in his article Essentiality of Mosque in The Hindu (external link).

Rahman further informs us that the Prophet did insist on offering prayers in mosques as it had 27 times more premium, and that even a blind person was advised to prefer a congregational prayer in a mosque.

Thus, the recent judgment denying the essentiality of mosques disregarded the Supreme Court verdicts of 1954 and 1972.

3. Such a pronouncement also violates Articles 25 and 26 of our Constitution which guarantees fundamental rights.

Adding to this, just for the sake of advancing the argument, please consider this hypothetical instance and then make a logical scrutiny of the issue of criminal vandalisation of the Babri Masjid in 1992, combined with the recent judgment declaring the non-essentiality of mosques in Islam.

A nomad happens to have owned a piece of land, constructs a house and starts living in it. Subsequently, a bunch of criminals come and snatch it away. The nomad-turned-sedentary goes to the court of law where he is told that since a home and sedentary life are not essential for a nomad, the criminal occupation of his house is justified.

The point being made here is that the jurisprudence of a modern secular State has to be strictly rational.

Rather than aastha and aqeedah, our jurisprudence as well as the executive and legislature have to act in accordance with Constitutional rationality.

This sacred document, which the people of India gave to themselves, encompasses the experiences of humanity over a span of many decades of evolving struggles against colonialism as the socio-cultural base of the people's struggles kept expanding and deepening.

This document did not come out of an individual's pen. It is wrong to assume that an oligarchy drafted it. Those who drafted it had taken into account the experiences of the national movement as well as the experiences gathered by people in different parts of the globe.

Only because of pressures from a frenzied majoritarian reaction, India and its institutions cannot afford to trample upon Constitutional rationalities.

Let us remain optimistic that the collective wisdom of India will not choose a perilous and self-destructive path for itself.

Professor Mohammad Sajjad, who is at the Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University, has published two books: Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours and Contesting Colonialism and Separatism: Muslims of Muzaffarpur since 1857.

© 2025

© 2025