December 3, 2021 marks 50 years since the beginning of the 1971 War which ended in a decisive military victory for India and the liberation of Bangladesh.

Most analysts of the 1971 War agree that the IV Corps dash across the mighty Meghna river led by the brilliant General Sagat Singh was the turning point in the war, recalls military historian Colonel Anil A Athale (retd).

Historical events are often best seen in greater clarity with distance in time and space.

Hindsight is always 20x20 and makes it possible to not just count the trees but see the woods.

The events of 1857, labelled as the 'Sepoy Mutiny' by the British came to be recognised as the First War of Indian Independence by 1907 thanks to Veer Savarkar's efforts. It often takes that long for the complete information concerning an event to emerge.

That moment has arrived for the re-assessment of the 1971 War in this Golden Year of that famous Indian victory.

A note of caution here, any critical appraisal of events and personalities of that time does not in any way diminish their stature as the major actors were then operating under the conditions of incomplete information and taking decisions in the 'fog of war'.

This article thus in no way wants to belittle those great personalities of that time.

Strategic aspects

Strategy, like any other discipline, has a rational foundation upon which logical doctrines and theories are discussed, conceived and implemented.

During the epoch of 'Agricultural Civilisation' in the history of mankind, India was at its peak.

India had a well-established strategic tradition, articulated by Chanakya (375 to 283 BC era) which dealt with threats on five fronts: the diplomatic, economic, social, psychological and military fronts.

From antiquity, the basic law in India was dharma.

The true sovereign of the State was dharma and the constitution enforced by the king was dand (punishment/stick).

Between dharma and dand the laws of peace and war developed.

War was never waged before peace efforts through diplomacy were completely exhausted.

This process followed four steps, similar in many ways to the four levels of modern strategic control, conciliation (sama), gifts (dama), sowing of dissension (bheda) and chastisement/force (dand).

During the War of 1971, Indira Gandhi's strategic perception and control on the five fronts was superb.

She used persuasion, hindrance and coercion on all five fronts without opening hostilities.

Military force was only used as a last resort when Pakistan launched an air attack on the western front.

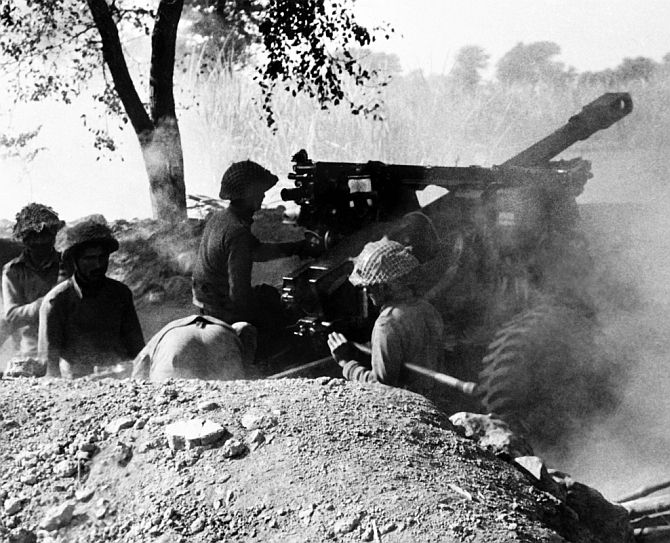

Men of the three services rose to the occasion and displayed tactical initiative and skill of a high order.

The War was a triumph for these individuals who transcended an out-of-date institutional politico-military decision-making system.

Initially, India had a modest aim of establishing an enclave in East Pakistan where the Bangladesh flag of freedom could be raised.

Then the aim was widened to embrace the capture of several major towns.

It soon became clear that the peripheral towns were heavily defended and overcoming Pakistani military strongholds would have been too costly.

Lieutenant General J F R Jacob conceived the strategy to bypass major strongholds.

The war aim then snowballed into a race for Dacca. The surrender of the capital before any major military strongholds or city had fallen resulted in the creation of Bangladesh.

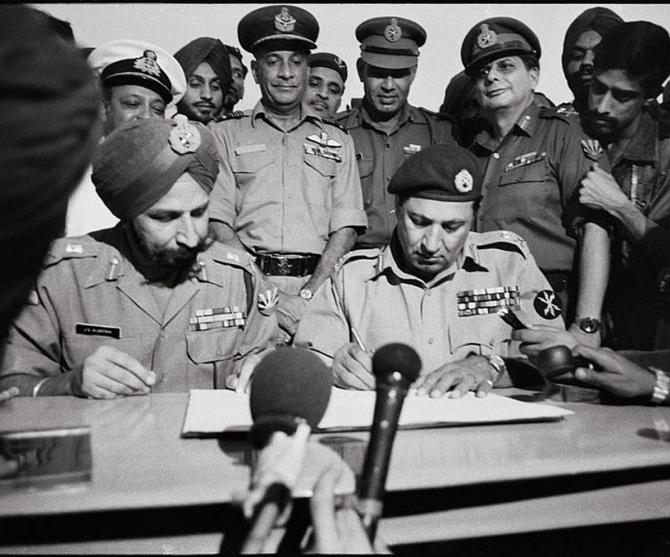

The War culminated in the capture of 93,000 Pakistani prisoners and a unilateral declaration of a cease-fire by India after our ground forces had made minor incursions into West Pakistan.

Most analysts of the 1971 War agree that the IV Corps dash across the mighty (3km wide) Meghna river led by the brilliant General Sagat Singh was the turning point in the war.

The Mi4 helicopter unit led by Wing Commander Chandan Singh heli-lifted 311 brigade in a daring operation to threaten Dacca from the East.

Pakistani defenders had destroyed the only bridge over the Meghna at Ashuganj and were sanguine that the Indian Army was blocked in that direction and was taken totally by surprise when Indian soldiers appeared at Naraynganj cantonment on December 10, 1971.

It was indeed a brilliant tactical move, but it must be remembered that this became possible only because of actions by the Indian Air Force on 6/7 December when the IAF fighters and bombers bombed the airfields and virtually grounded the Pakistani air force in the East.

The military balance in the air in the East was heavily tilted in India's favour.

As against the IAF's 161 operational aircraft consisting of Hunters, MiG 21s, Sukhoi 7 and Canberra bombers, the PAF only had 16 Sabre F-86 jets.

From 8 December onwards only Indian fighters were flying in the East Pakistani skies.

It is true that 8-10 Pakistani helicopters continued to fly right till the end of the war, but the skies over the battlefield were in total control of India.

It is this air supremacy that enabled the Meghna crossing.

In addition, it also made sure that the Pakistani higher command was virtually 'blind' as far as information about ground conditions and locations of advancing Indian columns.

This lack of information paralysed the Pakistani decision making and also enabled the Indian strategy of bypassing Pakistani strongholds.

In tandem with the Mukti Bahini (Bangladesh irregulars) and popular support to the Indian offensive, India achieved 'information domination' of the battlefield.

With close air support available for the ground offensive in terms of firepower as well as logistics, advancing the army on land could race to Dacca.

Constant air attacks by India and the total absence of PAF also took a heavy toll on Pakistani morale.

It is the loss of morale and information blackout that led to the Pakistan surrender at Dacca when various outposts and strongpoints still held firm and had ammunition and supplies to last 6 months.

The vital role played by air power in achieving victory on the ground has not been adequately understood or appreciated.

Even in the 1947 Kashmir War, it was the destruction of raiders transport by air action that paved the way to save Srinagar.

Logistically speaking it was the airlift of the army to the ashmir Valley on October 27, 1947 that saved Kashmir for India.

Inadequate understanding of this and over-emphasis on land action in 1947 led to the blunder of not using air power in 1962 when it could have turned the tables on the Chinese.

Even in the limited context of the Kargil clash of 1999, it was the use of airpower that won us victory.

The biggest lesson we must learn from 1971 is the importance of treating air-land operations as one.

Another and vital lesson is that the military must be associated when decisions vital for national security are being taken by the political leadership.

Post 1971 victory, a meeting between the two PMs resulted in the Simla Accord.

Once again, policy decisions involving vital security aspects were taken without adequate military inputs.

After the 1971 defeat, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto came to power in Pakistan. He kept blowing hot and cold, and under-took two hurricane tours of a number of countries where, in joint communiques issued from those capitals, calls were made for the speedy withdrawal of Indian troops from West Pakistani territory and for the immediate release and repatriation of POW.

Bhutto spoke with two voices. In Pakistan, he said, 'Your (Prisoners of War) humiliation is our humiliation and we will bend backwards to see to it that not a moment is wasted for correct results (their release from Indian custody)'.

Yet with India, Bhutto would show no great concern for their early return.

In these circumstances, there was nothing immoral or illegal about using the PoW issue as leverage to ensure a just and durable peace.

It appears that India wanted to do this but lacked the resolution to carry this out.

If we had no intention to use the PoWs as a bargaining counter, where was the need to hold them in custody for so long, earn the disapproval of the world community on their extended detention, and at the same time bear such a high financial burden?

It was nobody's case to demand war indemnity from Pakistan or to hold onto territory across the international border forever.

However, the issue of repatriation of POWs, Bangladesh's insistence on the trial of war criminals (about 1,500 PoWs were charged with genocide and serious violations of human rights), the climate of public opinion in Pakistan for their early return, the elimination of the army as a factor in the formulation of Pakistan's policies, and the withdrawal of Indian troops from Pakistani territory could all have served as levers to put pressure on Pakistan to accept a no-nonsense fair and just solution to the Kashmir problem.

Foreign observers, basing their views on those close to Bhutto, have pointed out 'that Bhutto was willing to forsake the Indian-held two-thirds of Kashmir and agree that the Cease Fire Line, to be negotiated, would gradually become the border between the two countries.'

However, India seems to have been confused about its war aim.

The Simla Accord was never linked to the issue of POWs and the withdrawal of Indian troops from Pakistani territory.

This was a major blunder on Indira Gandhi's part. When D P Dhar went to Pakistan for a pre-summit dialogue with Pakistani leaders, he was more concerned with the issue of recognition of Bangladesh by Pakistan than the core issue of finding a lasting solution to the Kashmir problem.

While India held all the cards at Simla, it was Bhutto who called all the shots.

It was then being propagated that the greatest merit of the Accord was that the two countries decided to renounce the use of force against each other.

But that commitment was jettisoned when Bhutto talked of a 1,000-year war, and later when Pakistan breached the Accord by launching cross-border terrorism in J&K.

IMAGE: Prime Minister Indira Gandhi with Pakistan Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in Shimla, July 1972.

Some career diplomats and commentators on foreign affairs have tried to sell the line that after the 1971 war, India was faced with only two courses of action: Either the Simla Accord or something on the lines of the Treaty of Versailles. They gave an erroneous impression that between these two extremes there was a complete vacuum.

In fact, there were many other possibilities, shades and gradations for a solution to some of the more vexatious problems between the two countries.

The International Herald Tribune pointed out that 'the Simla Conference apparently could reach agreement on none of the substantive issues dividing the two sides'. It was obvious that Indian negotiators never seriously linked those issues with the Simla Accord.

In the 1971 War, all attention was focused on the Eastern front.

On the Western front, Indian successes in Punjab, (Shakarhgarh, Chicken's neck near Akhnoor) and the thrust towards NayaChor in deserts were substantial.

We lost small areas in the Fazilka sector.

In Kashmir, Pakistan gained some territory in Chhamb as the Indian Army poised for an offensive was caught off guard by a Pakistani attack.

A determined Pakistani attack against Poonch was thwarted by superior Indian strength.

India captured strategic outposts in the Kargil area, posts that dominated the Srinagar-Ladakh road link and was a constant irritant.

In a war fought at the height of winter, the better-trained and equipped Indian mountain troops also captured vast areas north of Leh in the Partapur and Turtuk sector. With the exception of 'local' initiatives in Ladakh, largely due to valiant efforts of the great Colonel Chewang Rinchen and his Ladakh Scouts.

The rest of the Cease-Fire Line (as it was then called) did not see any major offensive action from our side. Kashmir was not an issue at all in that war.

Later at the Shimla peace conference, India brought in the Kashmir issue.

The Cease-Fire Line (agreed as per the Karachi agreement of 1949) was converted to the Line of Control of LoC, a sort of halfway house between a cease-fire line and the international border.

Though not marked on the ground, it is marked on the map in great detail after a joint ground survey.

But at the conference, it was also agreed to LET EACH SIDE RETAIN THE TERRITORY CAPTURED BY EACH OTHER IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR while withdrawing to its own side of the international border (Clause 6, section 4 and 5 Simla Agreement).

This created a peculiar situation in the areas bordering Jammu as India committed to withdraw from the captured area (since the captured areas were in Pakistani Punjab and not J&K), areas captured by Pakistan were to be retained by that country -- village Thakochak!

When this anomaly dawned on to the government it fielded the formidable Lieutenant General Prem Bhagat (Victoria Cross, and universally respected as a soldier in India and Pakistan) to stonewall and finally browbeat the Pakistanis who incidentally were technically right! The Thakochak episode showed the perils of keeping the military out of any negotiations even as advisors.

I had a chance to conduct an extensive study of all the official documents connected with this war (including the minutes of the meeting of the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs, the top decision making body in the country at the time).

In addition to this I had a consultation with a person who was part of the Cabinet Secretariat military wing.

This brought me to the conclusion that there is no hint that retention of captured territory in J&K was a considered policy of the Government of India BEFORE the war.

The armed forces were certainly not aware of it.

The effect of this lack of forethought was that on the Western front, much of the military effort was concentrated in the plains sector in Punjab, gains that had to be given up.

On the other hand, an excellent opportunity to consolidate Kashmir or strategic Pakistan-occupied areas was wasted. If India had plans to retain the captured territory in J&K, a major thrust towards Skardu or Gilgit could have threatened the land access between Pakistan and China.

Unlike in 1965 when the Chinese served an ultimatum, in 1971 due to the Soviet build up on the Sino-Soviet border on the Amur river border (of almost 44 divisions from the normal 3-4), China kept out of this conflict.

As India faces a Sino-Pak joint military threat in the North one can only rue the effect this blunder has had.

It is difficult to blame only the military leadership for this as in retrospect it appears that the decision to retain gains in Kashmir was a 'spur of the moment after thought'.

It is amazing to note the cavalier manner in which issues of war and peace continued to be dealt in independent India.

The plain truth is that India's political leaders and bureaucrats failed to assess Pakistan's predicament correctly, did not have a clear national aim, and were ignorant of the basic axioms shaping the role of the armed forces in democratic governance.

Our negotiators lacked the realisation that diplomatic treaties, which are not backed by military power are as worthless as a cheque issued on a dead account. They did not involve our military leaders in security policy planning.

After winning a stunning victory, Indian leaders behaved as if the armed forces had done something immoral or committed a sin.

The Simla Accord differed from the Tashkent Agreement on two counts.

Bi-lateralism was introduced; the issue of a final settlement of the J&K problem at some future date was brought in.

The former was never honoured by Pakistan, which at every opportunity tries to internationalise the Kashmir issue.

Anyway, of what use is bi-lateralism when both parties have completely closed their minds on the issue.

The ink of the Simla Accord had not even dried when Pakistani leaders began claiming that by mentioning in the Accord that it would be settled at a future date, India had thereby recognised Kashmir as 'disputed territory'.

Thus, in 1971, India lost an opportunity to move towards a lasting solution in J&K.

Gains made by soldiers shedding blood on the battlefield were frittered away on the negotiating table is the final verdict of history on the 1971 War.

Military historian Colonel Anil A Athale (retd) is a former Chhatrapati Shivaji Chair Fellow at the United Services Institute of India.

The colonel was a prisoner of war during the 1971 War and you can watch his recollections of the War:

- Colonel Anil A Athale Interview: Part One (External video link)

- Colonel Anil A Athale Interview Part Two (External video link)

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025