The Indians felt that if they acceded to Chinese claims in Ladakh, Beijing would simply be emboldened to press for further concessions in the future.

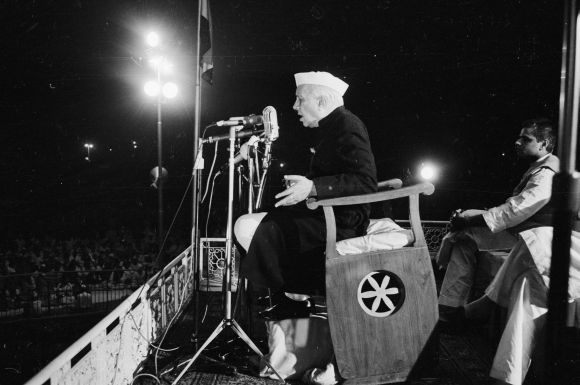

A revealing excerpt from India And The Cold War.

On April 20, 1960, Zhou Enlai, accompanied by Foreign Minister Chen Yi and other officials, reached Delhi.

The reception was in marked contrast to Zhou's earlier visits.

As a junior Indian official noted in his diary, 'The welcome was subdued, if not chilly. No 'Hindi-Chini bhai bhai' slogans. The tension was almost visible.'

The prime ministers held talks over seven sessions in five days.

In the opening session, Nehru spoke at length about Indian feelings on the boundary issue.

India had no doubts about its own frontiers, which had been 'clearly defined on our maps'.

His earlier discussions with Zhou had led him to believe that there were no major problems between the two sides: Only a few minor ones that could be settled by mutual consultations.

'What distressed us most was that if the Chinese government did not agree with us, they should have told us so. But for nine years nothing was said... these developments, therefore, came as a great shock.'

India did not agree with China's claim that the entire frontier was undefined and not delimited.

After laying out India's conception of, and basis for, the boundary, Nehru insisted that 'the question of demarcation of the entire frontier does not arise.'

Zhou responded to Nehru's points at the second session that evening.

China had stated that it did not recognise the McMahon Line, but was willing to take 'a realistic view'.

Zhou was 'shocked and distressed' that the Indian government used the Simla Convention in support of its claims.

Interestingly, he clarified that 'we only adduced proof that areas south of the McMahon line belonged to Tibet and that there was a customary line which later changed. We did not put forward any territorial claim.'

China had merely advocated maintenance of the status quo pending negotiations.

'There was only a misunderstanding on the part of India.'

Zhou was evidently suggesting that the position adopted on this sector by Beijing since September 1959 need not be taken at face value.

In the western sector, China had 'never thought that there was any question on that side.'

The treaty of 1842 mentioned by India made no specific reference to where the boundary lay.

History, administrative records, survey, and maps: All supported China's conception of this boundary.

Besides, since 1950 the Chinese had sent supplies and troops from Xinjiang to Tibet through this area.

'It was only last year that the matter was brought up by India and it was a new territorial claim made by India.'

This muddied the waters, for it led to some confusion among the Indians about what exactly the Chinese premier meant when he referred to territorial claims.

On the whole, Zhou averred that 'we have made no claims and we have only asked for status quo and negotiations.'

Nehru replied that 'our interpretation of not only history, but facts also differs greatly.'

Zhou might consider India's position as territorial claims, 'but when did we make these claims if our maps were wrong, as you hint, surely some idea could have been given to us, when we raised the question on many occasions.'

The McMahon Line, he emphasised, was based only on a reflection of earlier surveys: 'No new line was drawn.'

On the western sector, Nehru guardedly revealed his approach, stating that the Indians had visited parts of Ladakh that were now occupied by Chinese forces.

'I presume, therefore, that this occupation has taken place in the last year or two and is of recent origin.'

Nehru was more forthright in expressing his domestic constraints: 'Boundaries of India are part of the Indian Constitution and we cannot change them without a change in the Constitution itself.'

This failed to make any impact: The Chinese could not believe that the Indian political system could be much different from theirs.

When Zhou repeated that the status quo should be maintained before negotiations, Nehru replied: 'The question is what is the status quo? Status quo of today is different from status quo of one or two years ago... to maintain a status quo which is a marked change from the previous status quo would mean accepting that change. That is the difficulty.'

Zhou insisted that there had been no such change in the western sector: China had all along controlled the area it claimed.

'When we say status quo, we mean status quo prevailing generally after independence.'

The Indians refused to accept this claim.

They held that not only had China sidled westward from the Aksai Chin road over the previous year but that the Chinese still did not control all the areas (beyond Aksai Chin) claimed by them.

The prime ministers continued the exposition of their respective stances the next day. Nehru stated that the western sector was a large area.

'I do not know to which part of it your remarks apply. We are quite certain that large areas of it, if not the entire portion, were not in Chinese occupation...'

'Apart from the northern tip of the area... the Chinese forces seemed to have spread out to other parts... only in the last year-and-a-half.'

He insisted that there was a major dispute in this sector, but importantly added: 'We must, however, distinguish between eastern Ladakh and certain parts of it.'

This was consonant with his desire to reach an agreement that would cede to China control of the area around the road the Chinese had built.

Zhou laid out China's case in detail and stated that the areas it claimed had been under Chinese administrative jurisdiction since the 18th century.

He also pointed that India's control of the eastern sector had been established only in the early 1950s.

Nehru said that 'apart from minor dents' the eastern sector had never been under Chinese control.

India could not give up the watershed as the boundary in this area.

The Himalayas were dear to the Indian mind.

Besides, if the principle of the watershed as defining the boundary were given up, 'the whole country would be at the mercy of the power which controls the mountains and no government can possibly accept it.'

Seeking a way out of this impasse, Zhou suggested appointing a joint committee to look into the material that both sides possessed and possibly carry out investigations or surveys on the spot to ascertain the facts.

Meantime, the status quo should be maintained and troops on both sides pulled back to an agreed distance.

Nehru agreed that an examination of the material would be useful.

However, he felt that sending teams to the boundaries would be nugatory.

The question was not merely geographical, but political.

The committee could identify areas of divergence for the principals to consider.

On the morning of April 22, Zhou dealt with the problem in three parts: Facts, common ground, and a proposal.

After a detailed reprise of Beijing's position, he suggested the following as common ground. First, the boundaries had to be fixed by negotiations.

Second, there was a 'line of actual control' up to which the administrative personnel as well as patrolling troops of both sides had reached.

In the eastern sector, this was the McMahon Line.

In the western sector, 'the line is the Karakoram [range] and Konka [sic] pass.'

Third, the watershed was not the only geographical determinant of the boundary: Valleys and mountain passes should also count.

Fourth, neither side should advance claims to the area no longer under its administrative control.

There were 'individual places which need to be adjusted individually but that is not a territorial claim.'

Fifth, like the Indians the Chinese people, too, were emotionally attached to the Himalayas and the Karakoram mountains.

Zhou stated that he had 'come here mainly for reaching an agreement on principles.'

He proposed that they set a time limit for the joint committee to submit its report either jointly or separately.

Clearly, Zhou was suggesting that the basis of a final settlement should be China's acceptance of Indian control over the North East Frontier Agency and India's acceptance of China's control over the parts of Ladakh it claimed.

The third point indicates that in the western sector, the Chinese sought to press their claims to some areas south of the Karakoram watershed (which ended near Kongka Pass), including the Changchenmo valley, Pangong Lake area, and the Indus valley -- areas that they claimed had always been part of Tibet.

The third and fourth points together suggested that the Chinese also wished to possess some areas south of the watershed in the eastern sector.

This stemmed from two reasons.

Picking up the discussion the next day, Nehru insisted that it was essential to 'know definitely where our differences lie. My idea was that we should take each sector of the border and convince the other side of what it believes to be right.'

In so doing, Nehru sought to decouple the western and eastern sectors.

The Indians had begun to understand that it was by linking these that Zhou strove to obtain concessions from India in the western sector.

Following a lengthy recital of India's conception of the boundary in Ladakh, Nehru yet again distinguished between 'north Aksai Chin area' and 'other parts of eastern Ladakh.'

Zhou, for his part, insisted that both sectors should be considered together: 'When we talk about the western sector of the boundary, we should discuss it in relation to other sectors.'

At the start of the next session, Nehru sought yet again to pin down Zhou on when Chinese forces had moved into different parts of Ladakh.

He underscored his oft-repeated distinction between the area adjoining the road and other areas.

Zhou retorted that 'the case is precisely the same as the eastern sector where India regards the line of actual control as her international boundary.'

After further discussion, Nehru conceded that there was yawning gulf between the two sides' positions.

He mentioned again that 'even the slightest change in our border' would require an amendment of the Constitution.

Nehru agreed with Zhou that it was 'very difficult and unlikely for us to find a way of settlement on this occasion.'

Turning to the five points advanced by Zhou as common ground, he questioned the suggestion that neither side should put forth territorial claims: 'Our accepting things as they are would mean that basically there is no dispute and the questions ends there; that we are unable to do.'

Zhou explained that there should be 'no pre-requisites. Neither side should be asked to give up its stand.'

He also suggested issuing a joint communique on the talks.

A couple of hours later, officials from both sides met to draft the communique.

The Indian draft focused solely on the decision to appointment a joint committee to examine the material held by the countries.

The Chinese wanted the draft to include the points of common ground proposed by Zhou.

The meeting ended without a communique.

At the final prime ministerial session the next morning, Nehru made it clear that points advanced by Zhou were unacceptable and were not to be included in the communiqué.

Zhou frankly expressed his disappointment at the draft suggested by Nehru, but eventually he gave in.

After five days and nearly twenty hours of discussion, the only point of agreement was on appointing a joint committee.

The Delhi summit was the last occasion on which the two leaders met to discuss the boundary question.

By the time the officials' committees submitted their reports, events on the ground had overtaken meaningful diplomacy.

The 'forward policy' adopted by India to prevent the Chinese from occupying territory claimed by them was undertaken in the mistaken belief that Beijing would be cautious in dealing with India owing to Moscow's stance on the dispute and its growing proximity to India.

These misjudgements would eventually culminate in India's humiliating defeat in the war of October-November 1962.

The 'forward policy' and the defeat against China should not, however, lead to retrospective claims about India's stance on the dispute up to 1960.

Nehru's refusal to accept Zhou's suggestions for a solution cannot be attributed simplistically to his intransigence.

Indeed, until early 1960, Nehru was open to negotiation and compromise on Aksai Chin, the core Chinese interest.

He was unwilling, however, to treat the entire boundary as negotiable.

This position stemmed from long-standing apprehensions about China's territorial ambitions.

Beijing's handling of the issue bolstered these concerns and convinced Delhi that the Chinese were untrustworthy.

Further, Nehru's willingness to accommodate Chinese interests in Aksai Chin suggests that a solution such as a long-term lease of territory could have been worked out.

Here China's unyielding insistence that it had controlled the area for the previous two centuries queered the pitch.

In retrospect, this might not seem much of a concession.

But given the pressures on Nehru from parliamentary and public opinion, it might well have been the only feasible arrangement.

The Indians felt that if they acceded to Chinese claims in Ladakh, Beijing would simply be emboldened to press for further concessions in the future.

Scholars have often claimed that by turning down Zhou's suggestions for a deal Nehru passed up an excellent opportunity to arrive at a settlement, which would have respected both sides's principal interests.

Such claims, however, are made in the flat glare of hindsight.

More than fifty years on, it is easy to argue that a deal should have been struck with Zhou Enlai on his terms.

But opinion within (and outside) the Indian government at the time was overwhelmingly against any such bargain with the Chinese.

However appealing in hindsight, the argument fails the test of political plausibility -- just as the wider revisionist case fails the test of historical plausibility.

Excerpted from India And The Cold War, edited by Manu Bhagavan, with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House India.

© 2025

© 2025