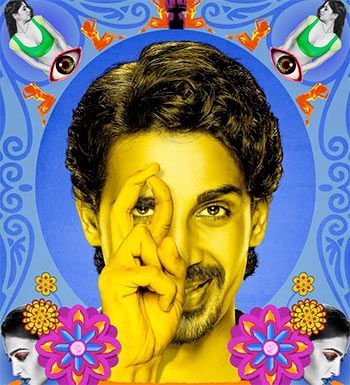

Hunterrr is a deeply problematic film, and fails rather miserably, warns Raja Sen.

Hunterrr is a deeply problematic film, and fails rather miserably, warns Raja Sen.

Is there a word for a male nymphomaniac? (If not, I strongly suggest ‘himphomaniac.’)

The film Hunterrr chooses to use the word Vaasu -- taken from the Sanskrit word vasana, meaning ‘truly stubborn desire’ -- and treats it like commonly used slang.

“I am a vaasu,” says the man with great revelatory import, trying to tell the woman he loves that he is a sex addict.

"Vaasu? As in?" she asks blankly, and here a truly smart film would have tossed in something bewilderingly funny and utterly unrelated. (“Vaasu? As in Sreenivasan Jain?”)

Alas, Hunterrr is not a truly smart film.

It is however brazen, ambitious and decidedly shameless in its celebration of sleaze.

It features a tremendously talented and markedly unconventional ensemble cast, and they conjure up some stirring moments. Above all, there is a sincere attempt at naturalism: Hunterrr tries to be the Malgudi Days of Masturbation. (It ends us being Mister Unlovely.)

It tries, flounders and -- despite the actors outshining one another -- fails rather miserably.

Written and directed by debutant Harshvardhan Kulkarni, Hunterrr is a deeply problematic film, one where young boys egg each other on to grope a lady at a fish-market, and where a man who coaxes a woman from airport waiting room to hotel room doesn’t consider asking her name or where she’s coming from.

Misogyny forms the spine of the film, coming in many shapes: a schoolboy declaring that the best girl isn’t attainable but the second best is; a father describing a boy’s aunt by saying “she looks okay”; a brother telling another that he might as well keep lying to his fiancee and tell the truth once the marriage is done.

It starts off with promise, thanks mostly to Gulshan Devaiah’s wonderful performance in the lead as Mandar Ponkshe, a Marathi version of Alexander Portnoy who has -- through indiscriminate standards and aggression -- managed to bully his way into a series of conquests.

It isn’t that he isn’t likeable; Mandar can be disarmingly warm and friendly, despite being a borderline sociopath. If I timed the film’s awful and sloppy back-and-forth-in-time structure correctly, Mandar should be just about 40. He’s hunting for a bride the arranged marriage way, and gets engaged, but can’t stop eye and zipper from roving.

Devaiah is overwhelmingly believable in the part, seeming to channeling Sai Paranjpye heroes as he slurps noisily from a straw or perpetually, needlessly fiddles with his belt. It’s a creepy role but he plays it very straight indeed.

Radhika Apte is reliably excellent as Tripti, his progressive fiancee, though it remains inexplicable why this seemingly sorted woman -- despite her sudden demand to know why someone may not have seen Mukul Anand’s Agneepath -- would settle for Mandar.

Sai Tamhankar brings power to the role of the attractive neighbourhood bhabhi, while a young man called Vaibhav Tavtavadi endows the studly-cousin character, Kshitij, with true charisma.

The young boys playing the childhood versions of Mandar and Kshitij -- Vedant Muchandi and Shalva Kinjawadekar -- are really very good, enough to declare that if this film had stayed in that 1989 flashback instead of hopping messily all over the place, we’d have something special on our hands.

The performance of the film comes from Sagar Deshmukh playing Dilip, Mandar’s relatively reticent elder brother. He’s a bit of a square and a sap -- a guy who tucked his knee under his outstretched t-shirt as he wept over a girl in college days, and, more importantly, the kind of guy who follows a drunken friend to the ends of the earth but not without taking the chicken lollipops along to eat in the auto-rickshaw.

There are, thus, nice little touches of detailing all over the place -- kids crowning each other “Wing Commander” because of the way they rule over certain wings of the housing society; a portly friend encouraged to dance frenetically at parties and rip his shirt off like Hulk Hogan; young boys taking a bath together and using soaping-the-back as a metaphor. But all this does is make you believe a film like this should exist, certainly, and that you want to like a film like this. Yet, the flat humour left me mostly unmoved, and I doubt you’ll be quoting fondly from this one unless you find the mere mention of swearwords inherently funny.

At one point in the film Mandar ‘fesses up to Tripti, following which she enticingly proposes that they leave their marriage open and go pick up couples from swinger parties.

She does this with eyes blessedly agleam (damn that Radhika Apte is good) and Mandar can’t believe his luck, till, it turns out she was messing with him only to see how depraved he is before she dumped him.

It’s a good moment of Mandar being put in his place... except it doesn’t happen.

The second half of the film consists of at least a half-dozen moments that are filmed but, we then realise, haven’t actually taken place. An unreliable narrator is one thing but Hunterrr, like Mandar, cheats too often.

Which is why it should come as no surprise that, at the scene mentioned at the head of this review, not just does the woman not invoke the bearded journalist, but she refuses even to behave like that other TV anchor and “demand to know.”

The hunt was never afoot.

Rediff Rating:

© 2025

© 2025