'...you start running after the star.'

'If the star says yes to the film, the ecosystem supports it.'

'The biggest cog in the wheel of the ecosystem is the audience and we forget that.'

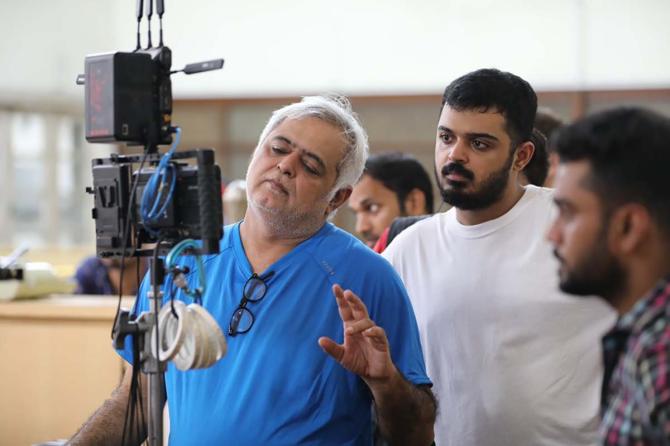

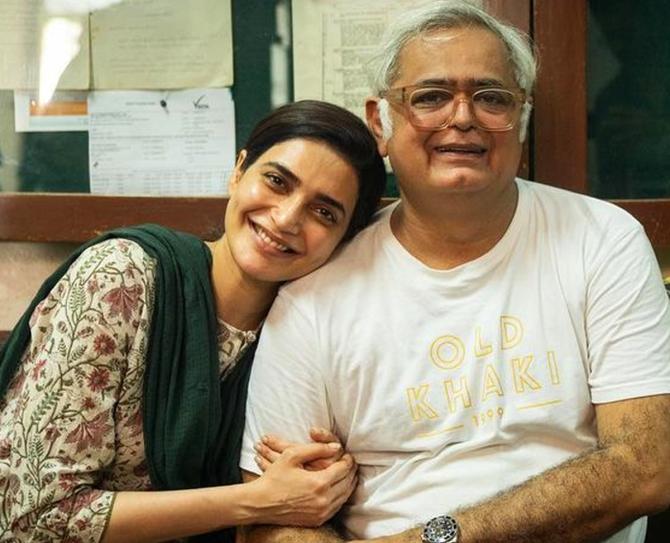

The success of Scoop, on Netflix, has once again put the limelight on Hansal Mehta, who also made Scam 1992, the 2020 show that revived SonyLIV, the Sony Pictures India-owned streaming platform.

Last month, Netflix signed a multi-year, multi-series partnership with Mehta.

In a conversation with the film-maker, Vanita Kohli-Khandekar/Business Standard finds out that the man earlier known for making award-winning movies that did not always run has found liberation -- creative as well as commercial -- on streaming platforms.

Feeling vindicated, Mehta says it is the quest for mass success that is destroying storytelling in movies.

What are the details of the Netflix deal? Does it also get Gandhi, the next show you are doing?

The contours of the deal are still broad. I am not at liberty to discuss it. Gandhi is being done by Applause Entertainment.

They will decide who to license it to. But as a storyteller, this long-term arrangement gives me encouragement and power that my work has a secure home.

What has the success of Scoop and Scam done for you?

They have vindicated my storytelling and the choice of stories I make.

This gives me the freedom to continue making those choices. It is very empowering.

You have always made the kind of films you wanted to make: Shahid, Citylights, Aligarh, Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar... Why does this feel more empowering?

That is true, but it was always a battle.

You were always told, 'film toh achi hai, par chalti nahin hai yaar (the film is good, but such films don't run).'

Somewhere the system sucks you in. 'Look you are a good film-maker,' they say, 'but I will teach you how to make a commercial film.'

That kept happening to me. I always believed that my style of storytelling was accessible and engaging.

While it was personal, it was not in any way alienating the audience.

It was only trusting the audience's intelligence. These shows and their success on OTT (over-the-top, another name for streaming platforms) have shown that if you trust the audience, there is a place for all kinds of stories.

Didn't television give you that space 20 years back?

I was a bit of a misfit in TV.

Except for Khana Khazana (ZEE TV), which was non-fiction and born out of a passion for food... nobody can remember all the fiction I did on TV. I can't, either.

It was only in the short form and anthologies that I would find my voice, off and on. But that format is not seen as popular.

Where does Indian cinema and storytelling stand right now?

We are a bit polarised in the kind of work you see.

There is new, exciting, cutting-edge work happening in the streaming space.

The long form has given impetus to storytellers like me, Vikram Motwane (Jubilee, Sacred Games), Raj and DK (The Family Man, Farzi).

Many of us have found it to be a comfortable space to do the kind of work we do and get money for it.

But, while that is happening, in the business we originally got into -- that of making movies -- there is a lot of chaos and confusion.

Every week we either ring the death knell of films or herald the beginning of a huge film.

This quest for mass success is destroying the kind of stories we are telling in films.

We have to look at our film work as a product of the budget, how much have we made it for and what is the return on this investment.

We are not deep diving into our own financial health. We are relying on outdated, trade-driven data.

One film out of X number of films works and you start running after the star.

If the star says yes to the film, the ecosystem supports it.

The biggest cog in the wheel of the ecosystem is the audience and we forget that.

What is streaming doing to the creative and business aspects of cinema?

I can only speak from my experience. Streaming has helped me find my audience.

For example, take my film, Faraaz. It released, it disappeared, nobody knew.

It reappeared on Netflix and found an audience.

It was on the top of the charts for nearly three weeks, not only in India but also other countries in Asia.

Does the screen (theatre, OTT, TV), the audience (global, Indian), or other variables affect the way you plan or approach a story?

It ultimately does, because there are metrics thrown at you.

There are learnings out of everything, and they are beyond the craft.

Earlier, all we had was box-office numbers and trends.

In the 1970s and 80s, it was silver jubilee. Then it became Friday or Saturday numbers. Then came the Monday test.

All these metrics were created, and failed, on a regular basis. But they guided your process.

Somewhere, these metrics are to blame for some of the films that get made.

Similarly, on streaming, there are metrics. We don't know and understand those metrics.

Ormax releases data week-on-week and streaming platforms say they haven't even shared that data.

So, how have they got it? It may say a show was watched by 6.1 million people. How much have they watched? What is the completion rate? Also, there are no comparative metrics.

If you watched a show on MX Player or JioCinema (both free platforms), and if my show is streaming on a subscription-based platform, how do you compare the two? Though these things are currently not a major factor, in the long term these are dangerous to the health of good storytelling.

Look at what TRP did to television.

On pre-production, writing and developing a script, and in creating a show, how are we placed compared to the rest of the world?

I think we are getting there. We have unfortunately had a very short learning curve.

We have just jumped into the long-form content game. We have not had our HBO moment.

Our TV, unfortunately, did not allow us to evolve as storytellers.

Sacred Games (one of the first major OTT shows) came in 2018. In the five years since, we have not done too badly.

We need to invest in writers, not only in paying them, but also in helping them evolve by taking them through workshops and exposing them to the kind of craft that is available. That is not happening.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025